You may have heard of Christian Bök. You may have read about him on this very blog if you’ve been hanging out here long enough. Perhaps you were even one of the very select few to witness the seminal talk I gave back in 2016[1]—“ScArt: or, How to Tell When You’ve Finished Fucking”— which climaxed with a glowing description of Bök’s magnum opus, then still in progress. And if you read Echopraxia, you’ll have encountered—without even knowing it— a brief cameo of that work near the end, suggesting that at least in the Blindopraxia timeline, he’d brought his baby to fruition.

Truth to tell, I didn’t know if he was actually going to pull it off for the longest time. I thought he’d given up years ago.

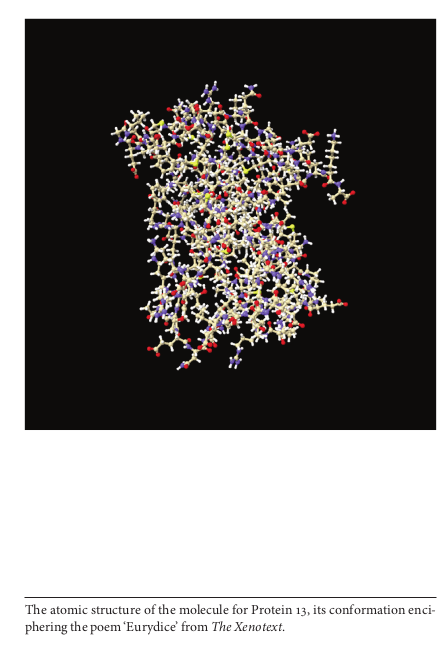

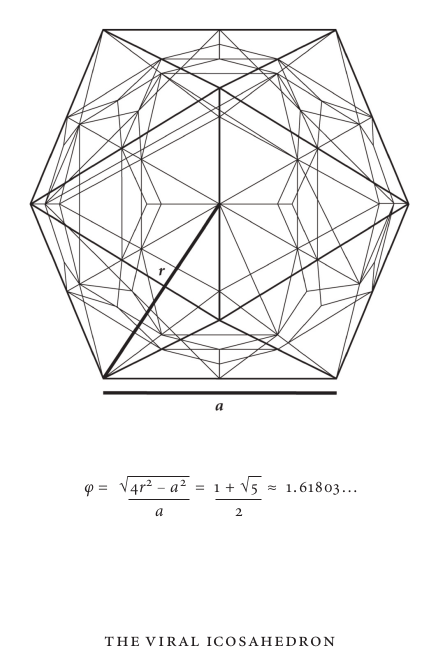

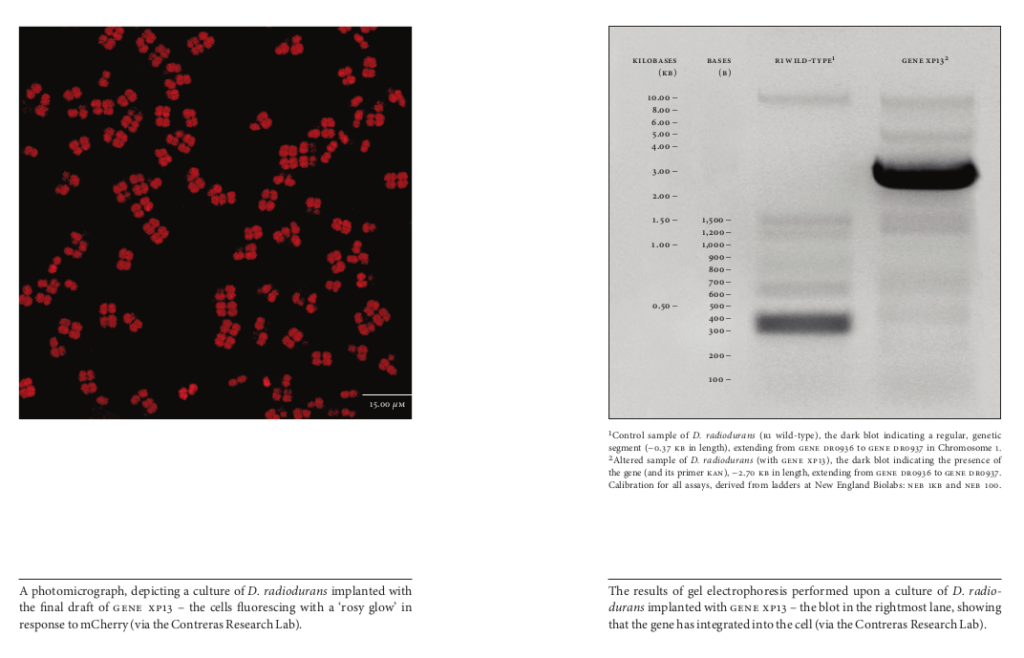

The story so far: back in the early two-thousands Christian Bök, famous for accomplishments lesser poets would never even dream of attempting (he once wrote a book in which each chapter contained only a single vowel) started work on the world’s first biologically-self-replicating poem: the Xenotext Experiment, which aspired to encode a poem into the genetic code of a bacterium. Not just a poem, either: a dialog. The DNA encoding one half of that exchange (“Orpheus” by name) was designed to function both as text and as a functional gene. The protein it coded for functioned as the other half (“Eurydice”), a sort of call-and-response between the gene and its product. The protein was also designed to fluoresce red, which might seem a tad gratuitous until you realize that “Eurydice”’s half of the dialog contains the phrase “the faery is rosy/of glow”.

Phase One involved engineering Orpheus and Eurydice into the benign and ubiquitous E. coli, just to work out the bugs. Ultimately, though, the target microbe was Deinococcus radiodurans: also known as “Conan the Bacterium” on account of being one of the toughest microbial motherfuckers on the planet. To quote Bök himself:

Astronauts fear it. Biologists fear it. It is not human. It lives in isolation. It grows in complete darkness. It derives no energy from the Sun. It feeds on asbestos. It feeds on concrete. It inhabits a gold seam on level 104 of the Mponeng Mine in Johannesburg. It lives in alkaline lakelets full of arsenic. It grows in lagoons of boiling asphalt. It thrives in a deadly miasma of hydrogen sulphide. It breathes iron. It breathes rust. It needs no oxygen to live. It can survive for a decade without water. It can withstand temperatures of 323 k, hot enough to melt rubidium. It can sleep for 100 millennia inside a crystal of salt, buried in Death Valley. It does not die in the hellish infernos at the Städtbibliothek during the firebombing of Dresden. It does not burn when exposed to ultraviolet rays. It does not reproduce via the use of dna. It breeds, unseen, inside canisters of hairspray. It feeds on polyethylene. It feeds on hydrocarbons. It inhabits caustic geysers of steam near the Grand Prismatic Spring in Yellowstone National Park.

I’d love to quote all seven glorious and terrifying pages, but to keep within the bounds of Fair Use I’ll skip ahead to the end:

It is totally inhuman. It does not love you. It does not need you. It does not even know that you exist. It is invincible. It is unkillable. It has lived through five mass extinctions. It is the only known organism to have ever lived on the Moon. It awaits your experiments.

As things turned out, it had to await somewhat longer than expected. The project hinged upon molecular techniques that did not exist when the experiment began. Christian taught himself the relevant skills— genetics, proteomics, coding— and enlisted a team of scientists (not to mention a supercomputer or two) to invent them. His audacity was more than merely inspiring; some might even call it infuriating. As I railed back in 2016:

It was fine when Art came to science in search of inspiration; that’s as it should be. I suppose it was okay— if a little iffy— when Science started going back to Art for solutions to scientific and technical problems. But this crosses a line: with The Xenotext, we have reached the point where Science is being used solely to assist in the creation of new art. Scientists are developing new techniques just to help Christian finish his bloody poem.

Up to now, we’ve generally been in the driver’s seat. Insofar as a relationship even existed, Science was the top, Art the Bottom. But Art has now started driving Science. Science has discovered its inner sub.

As a former scientist myself, I was not quite sure how to feel about that. But however that was, I knew Christian Bök was to blame.

Fortunately, Science got a reprieve. The project hit a bump at E. coli. Eurydice fluoresced but the accompanying words got mangled. When they eventually cleared that hurdle and moved to Phase Two, Deinococcus fought back, shredding the code before it ever had a chance to express. Conan, apparently, does not like people trying to play with its insides. It’s already got its genes set up just the way it likes them. Unkillable.

That, as far as I knew, was where the story ended ten years ago. Christian released The Xenotext: Book One in 2015, documenting his efforts and gift-wrapping them in some gorgeous and evocative bonus content, but the prize remained out of reach. He headed off to Australia to follow other pursuits; then to that oversurveilled and repressive shithole known as the United Kingdom. We fell out of touch. I assumed he’d given up on the whole project.

Oh me of little faith.

Because now it’s 2025, and he fucking did it. The Xenotext is live and glowing in Deinococcus radiodurans: iterating away inside that immortal microbial bad-ass that feeds on stainless steel, that resides inside the core of reactor no. 4 at Chernobyl, that does not die in the explosion that disintegrates the Space Shuttle Columbia during orbital reentry. Christian Bök did not give up. Christian Bök did not fail. Christian Bök is going to outlive civilization, outlive most of the biosphere itself.

The rest of us might think we achieve artistic immortality if our work lasts a century or three. Bök blows his nose at such puny ambitions. His work might get deciphered by Fermi aliens who finally make it to our neighborhood a billion years from now. It could be iterating right up until the sun swallows this planet whole.

It’ll almost certainly be around for Dan Brüks to find iterating in the Oregon desert, mere decades down the road.

The Xenotext: Book Two comes out from Coach House in June 2025. It would be well worth the price just for the the acrobatics and anagrams and sonnets, for the way it remixes science and fiction and the classic canon of dead white Europeans[2]. It contains poetry to entrance people who hate poetry. It juggles space exploration and the Fermi Paradox and the potentially extraterrestrial origins of Bacteriophage φx174. But its rosy flickering heart is that dialog iterating away in Conan even as I type. A reinvention, almost a quarter-century in the making. A fucking monument if you ask me, equal parts revelation and revolution.

If you happen to live in or around Toronto, it’s getting an official launch on May 27 at The Society Clubhouse, 967 College St, from 7-9pm. It’s one of a half-dozen Coach House titles that will be launched that night, and no doubt all six authors are worthy in their own right. Still. You know who I’m going for.

Maybe I’ll see some of you there.

We Welcome Our Cephalopod Overlords: Octopus!

Published on May 12, 2025

Credit: Prime Video

Credit: Prime Video

Just in time for this chapter of the Bestiary, Prime Video has debuted a new docuseries narrated by Phoebe Waller-Bridge and starring our favorite cephalopod. It’s a lighthearted and loving look at the octopus. “There does seem to be a unique connection between the human and the octopus,” our narrator tells us, despite the fact that we’re many millions of years removed from a common ancestor.

The series features scientist/quilter/octopus superfan named Dr. Jenny Hoffmeister, octopus specialist Piero Amodio, underwater photographer Luis Lamar, Greek fisherman/conservationist Giorgos, and entertainer Tracy Morgan, whose love for sea creatures and his giant aquarium serve as a sort of frame for the narrative (he doesn’t keep octopuses any longer, he couldn’t take the sadness of their short lives). It’s stitched together by Doris, an animated representative of the universal octopus. We follow her from the egg to the end, interspersed with various human perspectives.

The two episodes of the series hit all the main points. The weirdly wonderful anatomy. The venom that’s mostly harmless to humans but can paralyze and kill prey. The shape- and color-changing superpower. The ink. And particularly the intelligence, as represented in the opening sequence by Paul, the octopus who accurately predicted the winner of eight out of eight World Cup soccer games in 2010. Loser Argentina was so teed off that it threatened to turn him into a paella—complete with recipe. Then there’s the New Zealand octopus who staged a spectacular jailbreak from its aquarium. And the ones (plural) who have been observed to carry jellyfish spines as weapons.

But most of all, because we’re humans and that’s where our minds tend to go, we’re shown what to us is the great tragedy of octopus life: its short lifespan and its terminal reproductive cycle. Octopuses have no parental input. No raising, no nurture. Nobody teaches them how to octopus. Every one that survives attrition and predators to become an adult gets there on its own, with whatever knowledge or instinct is built in. It’s the diametrical opposite of humans with their long childhood and extensive parental and societal education.

Jenny observes that each arm of an octopus has its own brain; it has, in a phrase, nine minds. It also has taste receptors on the arms. When an octopus navigates across the ocean floor, it’s literally tasting every step. “Imagine the human tongue. Turn that into an animal.”

She wonders what that must be like. I think maybe there’s a distant correlation between an octopus tasting its floor and a dog’s nose mapping the world around it. They’re both super-senses by human standards, capabilities we can only begin to imagine.

Piero Amodio, like Jenny, is one of relatively few scientists who are willing or able to study octopuses in their native habitat. His particular interest is an even greater rarity: the larger Pacific striped octopus, which supposedly forms social groups. “It’s a kind of unicorn of octopuses,” he says, originally discovered in the 1970s by Arcadia Rodaniche. These octopuses lived in a colony off the coast of Nicaragua, and seemed to practice pair bonding and share food, behaviors which are not at all typical of octopuses in the wild.

Other scientists at the time were skeptical, but lab studies have supported some of Rodaniche’s findings. Octopuses in captivity have shared dens and food, and even had sex body to body instead of at arms’ length. It’s not impossible that a species of wild octopus may have done the things Rodaniche claims.

Piero sets out to find the supposed new species and its colony—“an underwater octopus Brigadoon.” A zebra-striped octopus has turned up in a fisherman’s net since Rodaniche’s expedition, so they do seem to be out there. Piero searches for it off the coast of Mexico, near Isla Magdalena.

It’s not the only example of apparent social gathering among a normally solitary species. There’s a place in Australia called “Octopolis” where octopuses appear to tolerate each other. They’ve been observed sharing small dens. But there’s been no study of their social structure, if any. Piero is inclined to think it’s not so much a fully functional city as a party town. Weekenders checking in for some fun in the, so to speak, sun.

His goal off Isla Magdalena is to find a colony and set up a longterm study. That doesn’t happen on this expedition. But that’s science. You don’t always find what you’re looking for. You just have to keep trying.

Maybe Piero doesn’t find his unicorn, but the giant Pacific octopus occupies front and center in the series, and there’s plenty of evidence and some amazing footage. When it hatches it’s minuscule, a tiny dot with arms, but it grows incredibly fast. At maturity it can weigh 400 pounds with a 27-foot arm span (says the series; it can get even bigger, supposedly, though on the average it’s more like 7-14 feet and under 100 pounds). We see it through Luis’ eyes and camera, “cruising the abyssal plain. It’s us and the animal 130 feet deep in the middle of the night.”

Octopus sex gets a big chunk of screen time, with diagrams and dramatizations, and an excerpt from Jacques Cousteau’s Les amours de la pieuvre, “The Love Life of the Octopus.” In the great man’s words, “The little male on the left, white from fear, reacts to the invitation of the female.” And then it gets technical.

The third right arm is the sex arm, Jenny tells us. Doris, our everyoctopus, stores the sperm of multiple males she meets. If she doesn’t want to mate with them, she eats them. (Which explains the part about fear.)

“Sex can be challenging,” Piero agrees.

So can being both predator and prey. We meet Giorgos as he pounds the hell out of an octopus that is about to become dinner. He represents the Greek octopus fishery, which is big business, but it’s in trouble because of overfishing.

And there’s an ethical quandary. Here we’re introduced to the Cambridge Declaration on Consciousness, a 2012 manifesto that acknowledges that some species show “evidence of near human-like levels of consciousness.” Among the animals listed are African grey parrots, orcas, magpies, great apes, and octopuses—the last through the pioneering studies of the inventor of the modern aquarium, Jeanne Villepreux-Power.

Her experiments, and others in almost two centuries since, have found that octopuses “can use tools, navigate mazes, plan ahead, and recognize humans, which demonstrate their complex cognitive abilities.” Does that mean they’re intelligent? That’s a tricky question.

Piero points out that humans tend to project our own thinking and behavior on the animals we study. We anthropomorphize. (Hence, in fact, naming our everyoctopus Doris and her featured lover Mike.) We have to learn to acknowledge that animals have different priorities. “They perceive the world in a different way. And their way of thinking will also be quite different from us.”

Piero draws an analogy to a primate’s baring of teeth. A human may interpret that as a smile, when in fact it’s a form of antagonistic display. And that’s an animal that shares 99% of its DNA with us.

Writer Sabrina Imbler begs to differ. She wants to connect her audience with the animals she writes about. Anthropomorphism for her is not a bad thing. They may be an alien intelligence, but they can do the same things we do, like solve a puzzle or escape from a tank. She uses animals as a reflection of her personal feelings and experience.

I have thoughts about this, but that’s a whole other article, and needs some more sources. We’ll get to those in future articles. Meanwhile, back on the beach, here’s a freaky-cool fact: Octopuses can survive out of water for up to an hour.

Cue random passerby discovering this up close and personal. EEK!

Fisherman Giorgos has a different angle on it all. Even as he acknowledges and respects the intelligence of the octopus, his livelihood depends on hunting and eating it. It’s about predator and prey, and economic survival.

I don’t think the octopus would feel much different about it. Octopuses eat anything they can get their arms on, including each other. Giorgos’ fishery actually helps scientists learn more about octopus population, varieties, and behavior.

In spite of the severe decline in numbers in Greek waters, Jenny believes the species is “fairly resilient to climate change.” A warming planet means hatchlings growing faster and reproducing more quickly. Ergo, more octopuses.

The diversity of octopus species—around 300 worldwide—is a key to its resilience. More diversity means more types of food available, and a higher chance of survival.

The symbol of it all, our animated Doris, comes to the end of her life as the second episode draws to its end. Giorgos too is looking at an ending, the slow demise of the Greek octopus fishery. He’s learned that the sea has to be protected in order to keep it, and us, alive.

Imbler meanwhile is finding personal connections with the octopus’ story. She’s read a newspaper article about a deep-sea octopus who brooded over her eggs for four and a half years. This gives rise to a wide range of feelings about human motherhood and the nature of sacrifice, as reflected in her own mother’s immigrant journey to the U.S. She muses about the octopus, and by extension about her mother: “I wanted to know if she ever regretted it.”

As the mother octopus dies, her eggs begin to hatch. The narrator starts to rhapsodize about what she must be feeling, but Jenny says whoa, stop. We have no idea. We can’t imagine. The mother dies, but that’s normal. That’s how she’s evolved. She’s meant to do that.

Tracy Morgan has his own take on the octopus’ lifespan. She gets a lot done in her four years. She’s born, grows up, finds a home, produces a family.

The planet, he goes on to say, is like the human body. It’s mostly water. We have to protect it. We have to care about it.

It all adds up to this: Everything is connected. Octopuses aren’t aliens. They’re descended from the same distant ancestor as humans. They belong to this planet just as much as we do.

Jenny shares a quotation that has stayed with her through her explorations of the octopus and its environment: “In the end, we will conserve only what we love. We will love only what we understand. And we will understand only what we are taught.” She doesn’t name the source, but it’s an excerpt from a speech delivered in 1968 by Senegalese environmentalist Baba Dioum.

The final lesson, and the ultimate point, is that we don’t have to make an octopus seem more human in order to care about him. What we need is what Jenny calls “radical empathy”: the ability to connect with creatures that are profoundly different from ourselves. That’s how we protect our future.

Because, she says, not entirely in jest, “They’re going to slowly take over the planet, become our overlords, and we just have to accept that.”[end-mark]

The post We Welcome Our Cephalopod Overlords: <i>Octopus!</i> appeared first on Reactor.