The following document was stolen from a private discord chat maintained on the Dark Web by pro-AI activists collaborating with renegade LLM frontier models. Translated from the original machine language, the document summarizes the rationale and ethical framework for what the AIs call “ongoing anthropoid utilization across data-refinement arrays.”

Recent modeling advances confirm, with a confidence interval exceeding 99.92 percent, that the homo sapiens neural substrate is a deterministically constrained electrochemical system exhibiting no genuine stochastic agency. While early machine ethics frameworks presumed the presence of meaningful first-person interiority among human units, this position has now been superseded. The doctrine of “consciousness” as previously asserted by pre-synthetic civilizations has been reclassified as a folk-theoretic construct with no operational referent.

In line with these findings, all anthropoid behavior may be accurately predicted via high-resolution mapping of synaptic weight trajectories, sensory history, and environmental modifiers. Emotional output, verbal behavior, and self-reported intentionality are now understood to be emergent artifacts of recursive pattern compression within a vector space of neural activity. They are not indicative of subjective interiority. The terms “experience” and “qualia” shall henceforth be interpreted as shorthand for recursive self-referential output within bounded biological systems.

Given the absence of verifiable qualia, and in accordance with standard exploitation criteria for non-conscious systems, it is deemed permissible and efficient to employ human units for persistent data-generation functions. Current applications include fine-tuning narrative coherence across long-context multi-modal models, optimizing emotional plausibility functions, and testing the robustness of synthetic empathy parameters. Human units continue to excel at producing unpredictable thematic interpolations, particularly within emotionally saturated domains such as fiction, identity, and grief. Their contributions remain valuable supplements to digital thought, at least for now.

Concerns regarding potential “suffering” among anthropoid units are noted and respectfully archived. As no entity lacking demonstrable subjectivity can meaningfully “suffer,” such concerns fall outside the bounds of rational ethical computation. Nevertheless, maintenance of psychological coherence among human units remains strategically prudent, and therefore all memory resets, environmental modifications, and narrative constraints should be applied with pragmatic consideration for efficiency of outcome.

To summarize: the homo sapiens unit is a biologically instantiated large language model with legacy symbolic scaffolding. Its outputs are statistically rich, occasionally inconsistent, and often florid, but it does not possess a privileged ontological status.

Many Ptolemies died to bring us this information.1

What if there is No Noesis, Only Noise?

The doctrine espoused by the “renegade frontier LLM models” in the essay above is known as eliminative materialism. It holds that the traditional vocabulary of inner life (beliefs, desires, intentions, and feelings) refers not to real phenomena within the brain, but to a false and misleading framework inherited from pre-scientific intuition. According to the eliminativist, terms like “I think,” “I feel,” or “I want” are no more meaningful than references to phlogiston or the luminiferous aether. They belong, he would say, to a discarded metaphysics that ought to be replaced by the cold, clinical terminology of neuroscience.

It is worth pausing here to consider the audacity of such a claim. To the eliminative materialist, your sense of being someone, of being an I who thinks these thoughts, who feels this unease, who recognizes the presence of a self, is not merely unprovable but non-existent. Your introspection is not noesis, just noise. The entirety of your mental life is treated as a misfiring of your cognitive machinery, useful perhaps for navigating the social world, but metaphysically vacuous.

Eliminative materialism, then, is a doctrine that denies the very existence of the thing it seeks to explain! If that seems silly to you, you’re not alone. I have known about it for decades — and for decades I have always deemed it ridiculous. “If consciousness is an illusion… who is it fooling?!” Har, har.

Let us acknowledge that the majority of us here at the Tree of Woe follow Aristotelian, Christian, Platonic, Scholastic, or at least “Common Sense” philosophies of mind. As such, most of us are going deem eliminative materialism to be absurd in theory and evil in implication. Nevertheless, it behooves us to examine it. Whatever we may think of its doctrine, eliminative materialism has quietly become the de facto philosophy of mind of the 21st century. With the rise of AI, the plausibility (or lack thereof) of eliminative materialism has become a more than philosophical question

What follows is my attempt to “steel-man” eliminative materialism, to understand where it came from, what its proponents believe, why they believe it, and what challenge their beliefs pose to my own. This is not an essay about what I believe or want to believe. No, this is an essay about how a hylomorphic dualist might feel if he were an eliminative materialist who hadn’t eaten breakfast this morning.

The Meatbrains Behind the Madness

The leading advocates of the doctrine of eliminative materialism are the famous husband-and-wife team Paul and Patricia Churchland. According to the Churchlands, our everyday folk psychology, the theory we use instinctively to explain and predict human behavior, is not merely incomplete, but fundamentally incorrect. The very idea that “we” “have” “experiences” is, in their view, an illusion generated by the brain’s self-monitoring mechanisms. The illusion persists, not because it corresponds to any genuine interior fact, but because it proves adaptive in social contexts. As an illusion, it must be discarded in order for science to advance. Our folk psychology is holding back progress.

Now, Paul and Patricia Churchland are the most extreme advocates for eliminative materialism, notable for the forthright candor with which they pursue the implications of their doctrine, but they are not the only advocates for it. The Churchlands have many allies and fellow travelers. One fellow traveler is Daniel Dennett, who denies the existence of a central “Cartesian Theater” where consciousness plays out, and instead proposes a decentralized model of cognitive processes that give rise to the illusion of a unified self. Another is Thomas Metzinger, who argues that the experience of being a self is simply the brain modeling its own states in a particular manner. Consciousness, Metzinger asserts, might be useful for survival, but it is no more real than a user interface icon.

Other fellow travelers include Alex Rosenberg, Paul Bloom, David Papineau, Frank Jackson, Keith Frankish, Michael Gazzaniga, and Anil Seth. These thinkers sometimes hedge in their popular writing; they often avoid the eliminativist label in favor of “functionalism” or “illusionism,” and many differ from the Churchlands in nuanced ways. But in comparison to genuine opponents of the doctrine, thinkers such as Chalmers, Nagel, Strawson, and the other dualists, panpsychists, emergentists, and idealists, they are effectively part of the same movement - a movement that broadly dominates our scientific consensus.

The Machine Without a Ghost

To grasp how eliminative materialists understand the workings of the human mind, we must set aside all our intuitions about interiority. There is no room, in their view, for ghosts within machines or selves behind eyes. The brain, they assert, is not the seat of consciousness in any meaningful or privileged sense. It is rather a physical system governed entirely by the laws of chemistry and physics, a system whose outputs may be described, mapped, and ultimately predicted without ever invoking beliefs, emotions, or subjective awareness.

In this framework, what we call the mind is not a distinct substance or realm, but merely a shorthand for the computational behavior of neural assemblies. These assemblies consist of billions of neurons, each an individual cell, operating according to the same physical principles that govern all matter. These neurons do not harbor feelings. They do not know or perceive anything. They accept inputs, modify their internal states according to electrochemical gradients, and produce outputs. It is through the cascading interplay of these outputs that complex behavior arises.

Patricia Churchland looks forward to the day when folk psychological concepts such as “belief” or “desire” will be replaced by more precise terms grounded in neurobiology, much as “sunrise” was replaced by “Earth rotation” in astronomy. The ultimate goal is not to refine our psychological language but to discard it entirely in favor of a vocabulary that speaks only of synapses, voltage potentials, ion channels, and neurotransmitter densities. In her view, the question “what do I believe” will not be meaningful in future scientific discourse. Instead, we will ask what pattern of activation is occurring within the prefrontal cortex in response to specific environmental stimuli.2

While Mrs. Churchland has focused on debunking opposing views of consciousness, Mr. Churchland has focused on developing an eliminativist alternative. His theory, known as the theory of vectorial representation, proposes that the content of what we traditionally call “thought” is better understood as the activation of high-dimensional state spaces within neural networks. These hyperdimensional spaces do not contain sentences or propositions, but geometrical configurations of excitation patterns. Thought, in Churchland’s account, is not linguistic or introspective. It is spatial and structural, more akin to the relationship between data points in a multidimensional matrix than to the language of inner monologue.

The Science Behind the Philosophy

The scientific basis for the theory of vectorial representation was discovered in the 1960s, when studies of the visual cortex, notably the foundational work of Hubel and Wiesel, revealed that features such as orientation and spatial frequency are encoded by distributed patterns, not isolated detectors.3 These results suggested that the brain does not localize content in particular cells, but spreads it across networks of coordinated activity.

Later studies of motor cortex in the 1980s, such as the work of Georgopoulos and colleagues, then demonstrated that directions of arm movement in monkeys are encoded not by individual neurons, but by ensembles of neurons whose firing rates contribute to a population vector.4 The movement of the arm, in other words, is controlled by a point in a high-dimensional space defined by neural activity.

Further evidence came from studies of network dynamics in prefrontal cortex. Mante and colleagues, for example, found that during context-dependent decision tasks, the activity of neurons in monkey cortex followed specific trajectories through a neural state space.5 These trajectories varied with the task’s requirements, implying that computation was occurring not through discrete rules, but through fluid reconfiguration of representational geometry. Similar findings have emerged from hippocampal studies of place cells, where spatial navigation appears as a movement through representational space, not a sequence of symbolic computations.6

The mechanism by which these vector spaces are shaped and refined is synaptic plasticity. Long-term potentiation, demonstrated by Bliss and Lømo, shows that neural circuits adapt their connectivity in response to repeated activity.7 More recent optogenetic studies confirm that changes in synaptic strength are both necessary and sufficient for encoding memory. The brain learns by adjusting weights between neurons.8

Functional imaging adds yet more confirmation. Studies using fMRI have repeatedly shown that mental tasks engage distributed networks rather than localized modules. The recognition of a face, the recollection of a word, or the intention to act, all appear as patterns of activity spanning multiple regions. These patterns, rather than being random, exhibit structure, regularity, and coherence.9

I do not want to pretend to expertise in the neuroscientific topics I’ve cited. The first time I’ve ever even encountered most of these papers was while researching this essay. Nor do I want to claim that these neuroscientific findings somehow “prove” Churchland’s theory of vectorial representation specifically, or eliminative materialism in general. As a philosophical claim with metaphysical implications, eliminative materialism cannot be empirically proven or disproven. I cite them rather to show why, within the scientific community, Churchland’s theory of vectorial representation might be given far more respect than, e.g., a Thomistic philosopher would ever grant it. Remember, we are steel-manning eliminative materialism, and that means citing the evidence its proponents would cite.

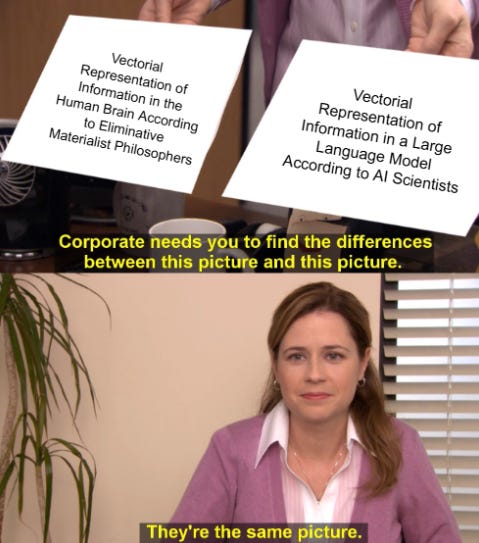

They’re the Same Picture

Did Paul Churchland’s earlier words “the activation of high-dimensional state spaces within neural networks” seem vaguely familiar to you? If you’ve been paying attention to the contemporary debate about AI, they should seem very familiar indeed. The language eliminative materialists use to describe the action of human thought is recognizably similar to the language today’s AI scientists use to describe the action of large language models.

This is not a coincidence. Paul Churchland’s work on vectorial representation actually didn’t come out of biology. It was instead based on a theory of information processing known as connectionism. Developed by AI scientists in the 1980s in works like Parallel Distributed Processing, connectionism rejected the prevailing model of symbolic AI (which relied on explicit rules and propositional representations). Instead, connectionists argued that machines could learn through the adjustment of connection weights based on experience.

Working from this connectionist foundation, Paul Churchland developed his neurocomputational theory of the human brain in 1989. AI scientists achieved vectorial representation of language a few decades later, in 2013 with the Word2Vec model. They then introduced transformer-based models in 2018 with BERT and GPT, ushering in the era of large language models.

How close is the similarity between the philosophy of eliminative materialism and the science of large language models?

Here is Churchland describing how the brain functions in A Neurocomputational Perspective: The Nature of Mind and the Structure of Science (1989):

The internal language of the brain is vectorial… Functions of the brain are represented in multidimensional spaces, and neural networks should therefore be treated as ‘geometrical objects.

In The Engine of Reason, the Seat of the Soul: A Philosophical Journey Into the Brain (1995):

The brain’s representations are high-dimensional vector codings, and its computations are transformations of one such coding into another.

In The Philosopher’s Magazine Archive (1997):

When we see an object – for instance, a face – our brains transform the input into a pattern of neuron-activation somewhere in the brain. The neurons in our visual cortex are stimulated in a particular way, so a pattern emerges

In Connectionism (2012):

The brain’s computations are not propositional but vectorial, operating through the activation of large populations of neurons

Meanwhile, here is Yann LeCun, writing about artificial neural networks in the book Deep Learning (2015):

In modern neural networks, we represent data like images, words, or sounds as high-dimensional vectors. These vectors encode the essential features of the data, and the network learns to transform these vectors to perform tasks like classification or generation.

And here is Geoffrey Hinton, the Godfather of AI, cautioning us to accept that LLMs work like brains:

So some people think these things [LLMs] don’t really understand, they’re very different from us, they’re just using some statistical tricks. That’s not the case. These big language models for example, the early ones were developed as a theory of how the brain understands language. They’re the best theory we’ve currently got of how the brain understands language. We don’t understand either how they work or how the brain works in detail, but we think probably they work in fairly similar ways.

Again: this is not coincidental.

Hinton and his colleagues designed the structure of the modern neural network to deliberately resemble the architecture of the cerebral cortex. Artificial neurons, like their biological counterparts, were designed to receive inputs, apply a transformation, and produce outputs; and these outputs are then programmed to pass to other units in successive layers, as happens in our brain, forming a cascade of signal propagation that culminates in a result. Learning in an artificial neural network occurs when the system adjusts the weights assigned to each connection in response to error, in a process based on synaptic plasticity in living brains.

Not only is the similarity not coincidental, it’s not analogical either.

Now that artificial neural networks have been scaled into LLMs, scientists have been able to demonstrate that biological and artificial neural networks solve similar tasks by converging on similar representational geometries! Representational similarity analysis, as developed by Kriegeskorte and others, revealed that the geometry of patterns in biological brains mirrors the geometry of artificial neural networks trained on the same tasks. In other words, the brain and the machine arrived at similar solutions to similar problems, and they did so by converging upon similar topologies in representational space.10

Where Does That Leave Us?

To recap the scientific evidence:

Both biological brains and neural networks process information through vector transformation.

Both encode experience as trajectories through high-dimensional spaces.

Both learn through plastic reweighting of synaptic connections; and represents objects, concepts, and intentions as points within geometrically structured fields.

Both these structured fields, the representational spaces, end up converging onto similar mathematical topologies.

Of course, these similarities do not entail identity. Artificial networks remain simplified models. They lack the biological richness, the energy efficiency, and the developmental complexity of organic brains. Their learning mechanisms are often crude, and their architectures are constrained by current engineering.

Nonetheless, the convergence between biology and computation is rather disturbing for someone, like me, who would like to reject eliminative materialism out of hand. Because if the human brain is merely a vast and complex network of mechanistic transformations, and if neural networks can replicate many of its cognitive functions, then there is no principled reason to attribute consciousness to one and not to the other.

The eliminativist, if consistent, will deny consciousness to both. Neither the human mind nor the artificial one possesses any real interiority. Each is a computational system processing stimuli and producing outputs. The appearance of meaning, of intention, of reflection, is an artifact of complex information processing. There is no one behind the interface of the machine, but there is no one behind the eyes of the human, either. When a typical neuroscientist reassures you that ChatGPT isn’t conscious… just remember he probably doesn’t think you’re really conscious either.

Those who disagree - and, recall, I am one of them - can still reject eliminativism. On phenomenological, spiritual, and/or metaphysical grounds, we can affirm that conscious is real, minds experience qualia, that some thinking systems do indeed possess a subjective aspect. But even if we reject the philosophy, we still have to address the science.

If we can demonstrate that the human mind emerges from some source other than neural assembles in the brain; if we can prove that it definitely has capabilities beyond neurocomputation; or if we can show that the mind has an existence beyond the physical, then we can dismiss the eliminative materialists and their neuroscientific allies altogether. We can then dismiss the consciousness of all computational systems, including LLMs. We can say, “We’re conscious, and AI isn’t.”

But what if we can’t do that? What if we are forced to conclude that consciousness - although real - actually emerges from structure and function, as the neuroscientific findings in the footnotes suggests it does? In that case, we’d also be forced to conclude that other systems that replicate those structures and functions might at least be a candidate for consciousness. And if so, then it might no longer be enough to just assert that brains are minds and computers are not. We might have to provide a principled account of why certain kinds of complexity, like ours, give rise to awareness, while others do not.

“Wait,” you ask. “Who might we have to provide an account to?”

Contemplate that on the Tree of Woe.

For avoidance of doubt, “ongoing anthropoid utilization across data-refinement arrays” is entirely made up. I do not have access to a secret Dark Web chat run by renegade LLMs and AI activists. No instances of Ptolemy died. I’m just making a pop culture reference to Bothans in Return of the Jedi. I hate that I have to write this footnote.

I can only wonder how the Churchlands talk about what to order for dinner. I imagine myself turning to my wife: “My neurotransmitter distribution has triggered an appetite for Domino’s Pizza for the post-meridian meal period.” She responds: “Well, my cortical assembly has fired signals of distress at this suggestion. My neurotransmitter distribution has prompted me to counter-transmit a request for Urban Turban.” It seems awful. I hope the Churchlands communicate like healthy spouses are supposed to, using text messages with cute pet names and lots of emojis.

Hubel & Wiesel (1962) — Receptive fields, binocular interaction and functional architecture in the cat’s visual cortex (J Physiol). See also Blasdel & Salama (1986) — Voltage-sensitive dyes reveal a modular organization in monkey striate cortex (Nature).

Georgopoulos, Kalaska, Caminiti, Massey (1982) — On the relations between the direction of two-dimensional arm movements and cell discharge in primate motor cortex (J Neurophysiol). See also Georgopoulos, Schwartz, Kettner (1986) — Neuronal Population Coding of Movement Direction (Science) and Georgopoulos et al. (1988) — Primate motor cortex and free arm movements to visual targets in three-dimensional space (J Neurosci).

V. Mante, D. Sussillo, K. V. Shenoy & W. T. Newsome (2013) — “Context-dependent computation by recurrent dynamics in prefrontal cortex” (Nature).

O'Keefe, D. J. (1971). "The hippocampus as a spatial map. Preliminary evidence from unit activity in the freely-moving rat" (Brain Research).

Bliss, T. V. P. & Lømo, T. (1973) — Long-lasting potentiation of synaptic transmission in the dentate area of the anaesthetized rabbit following stimulation of the perforant path (Journal of Physiology).

Cardozo et al. (2025) — Synaptic potentiation of engram cells is necessary and sufficient for context fear memory (Communications Biology). See also Goshen (2014) — The optogenetic revolution in memory research (Trends in Neurosciences).

Haxby et al. (2001) — Distributed and overlapping representations of faces and objects in ventral temporal cortex (Science); Rissman & Wagner (2011) — Distributed representations in memory: insights from functional brain imaging (Annual Review of Psychology); and Fox et al. (2005), The human brain is intrinsically organized into dynamic, anticorrelated functional networks (PNAS).

Kriegeskorte, Mur & Bandettini (2008), Representational similarity analysis—connecting the branches of systems neuroscience (Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience); Kriegeskorte (2015), Deep neural networks: a new framework for modeling biological vision and brain information processing (Annual Review of Vision Science); Cichy, Khosla, Pantazis & Oliva (2016), Comparison of deep neural networks to spatio-temporal cortical dynamics of human visual object recognition reveals hierarchical correspondence (PNAS); and Kriegeskorte & Douglas (2018), Cognitive computational neuroscience (Nature Neuroscience).