Biocubes is a visualization comparing the mass of the living world (biomass) to the mass that’s been generated by humans (technomass). From a piece in the Times about the visualization:

“The website enables many comparisons that, once seen, can no longer be unseen,” he said. For instance, humans outweigh wild animals 10 to 1, a fact that surprised Dr. Ménard. (“In my experience, most people expect the opposite.”) But we weigh only half as much as the livestock herds we maintain to eat. Perhaps more ominously, humans use 100 times their own mass in plastic.

Tags: infoviz

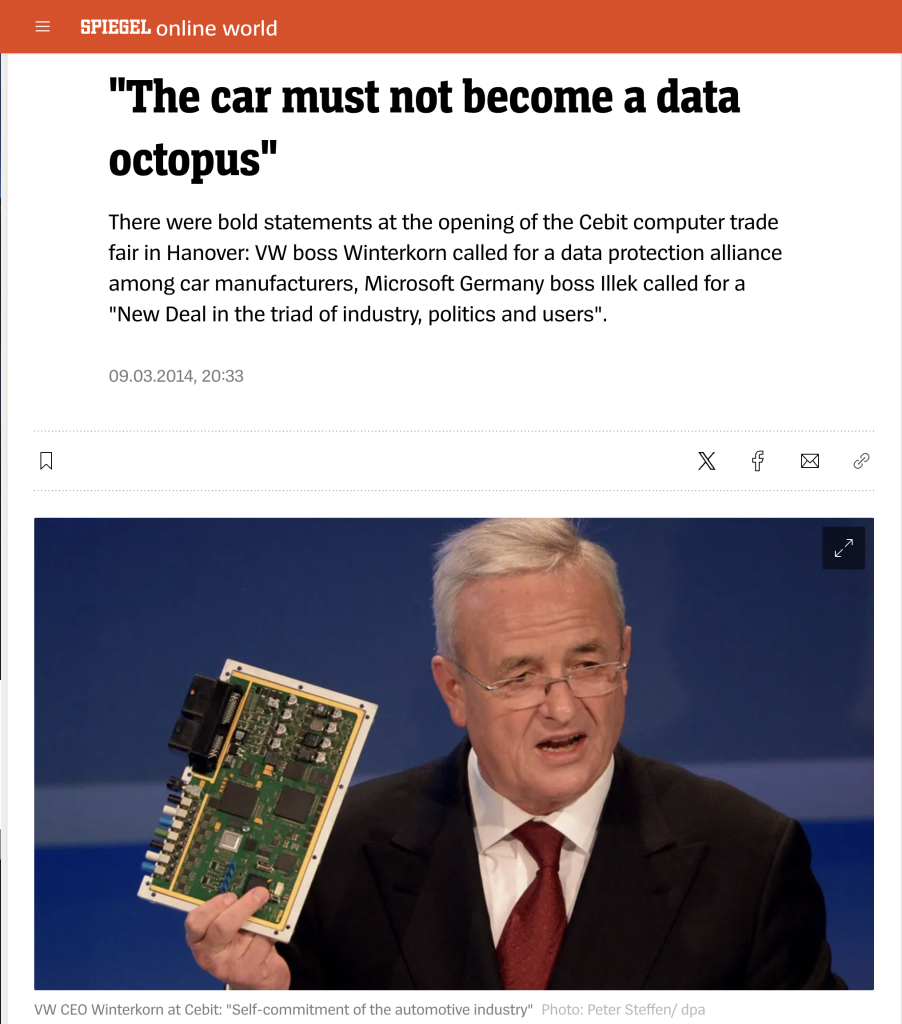

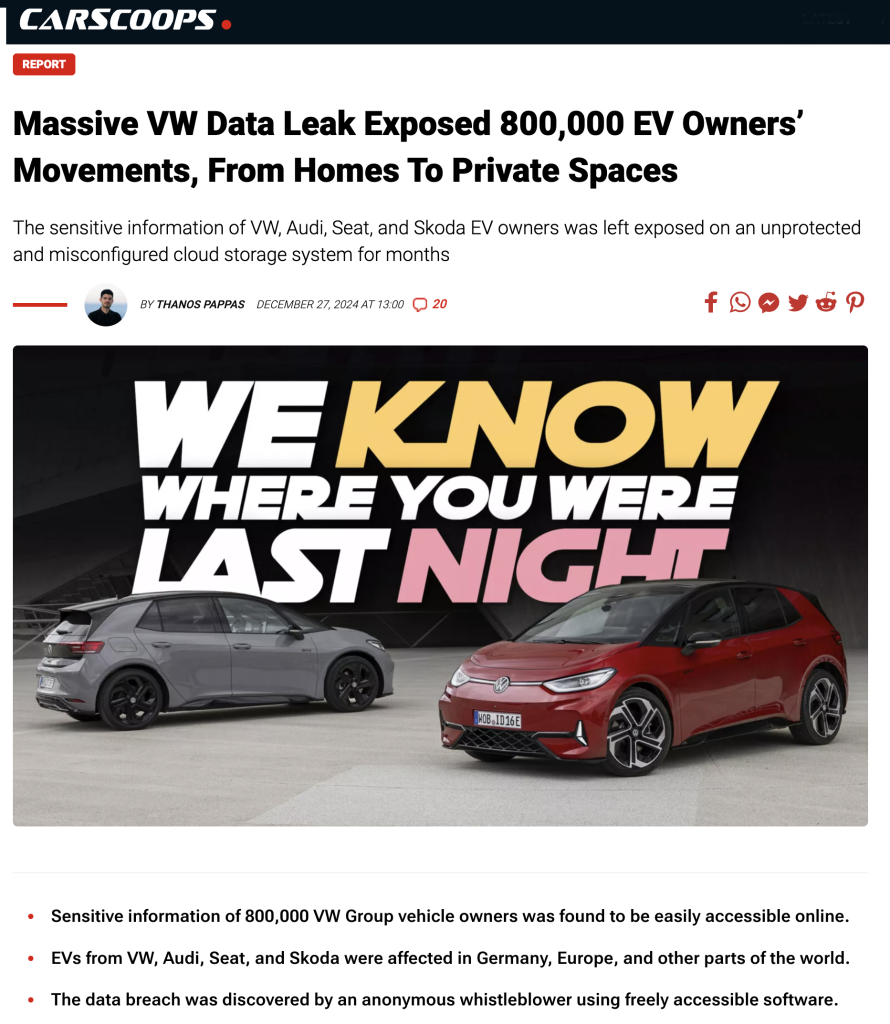

Imagine what would have happened had Martin Winterkorn not imploded, and if Volkswagen, under his watch, had not become a datakranken (data sea-monster, or octopus), spying on drivers and passengers—just like every other car company.

What would the world now be like if Volkswagen since 2014 had established itself as the only car maker not operating datakranken? Or, better yet, if Volkswagen became the one car company collecting data for the cars’ owners first—and for insurance companies and advertisers only by the grace of those owners?

Volkswagen would be for privacy what Volvo was (and maybe still is) for safety—or that Apple is (or wants to be) for privacy. It would have been a brilliant position for VW.

But no. Winterkorn went down, and now Volkswagen is just as bad as the rest of them. Maybe worse:

conference”), which was about to happen in Detroit. The post created a stir. Everybody I talked to about it at the time was enthused about what I recommended: integrating broadcast signals with the Net, giving collected data to car owners first, switching to the European RDS standard (which would relieve drivers of needing to retune to other signals just to stay with one station), among other ideas.

conference”), which was about to happen in Detroit. The post created a stir. Everybody I talked to about it at the time was enthused about what I recommended: integrating broadcast signals with the Net, giving collected data to car owners first, switching to the European RDS standard (which would relieve drivers of needing to retune to other signals just to stay with one station), among other ideas.

None of that happened. The flywheels of surveillance capitalism were already too big. Apple and Google were about to turn the dashboard into a phone display with CarPlay and Android Auto. Broadcast radio is now a distressed asset, a walking anachronism. It is being eaten alive on the music side by streaming and on the talk side by podcasting.

But the bigger thing is that we lost the chance for one big car maker to stake a position on personal privacy. Volkswagen could have done it. But it didn’t. And the datakraken won.

For now.

.

Here's a random memory: Back in the seventies, there was an underground comix series called Insect Fear which basically tried to outdo EC Horror comics. I was talking with then-Philadelphian friend Judith Weiss about the latest issue, which she had also read, and she amiably dismissed it by saying, "They should have called it Women Fear."

In an instant, I saw her point: Every story in the book had an assertive, large-breasted woman who received her violent comeuppance at the end. I had missed this not because I sympathized with the underlying misogyny but because the stories were all made up of narrative tropes that went way, way back to EC and long before. I was so used to them that I couldn't actually see them.

And a small observation: I was reading something about the old hippie days of the sixties and seventies which presented feminism of the time as being little more than a list of complaints. And God knows women had good reason to complain. But I was there and I can assure you that the feminists were rarely "strident." Mostly, they calmly explained things they knew that men didn't understand. They assumed that you'd mend your ways once you saw what they were.

Perhaps they were giving us more credit than we deserved. But we shouldn't portray them in a negative manner when all they were trying to do was make the world a kindlier and saner place.

End of sermon. Go thou and sin no more.

*

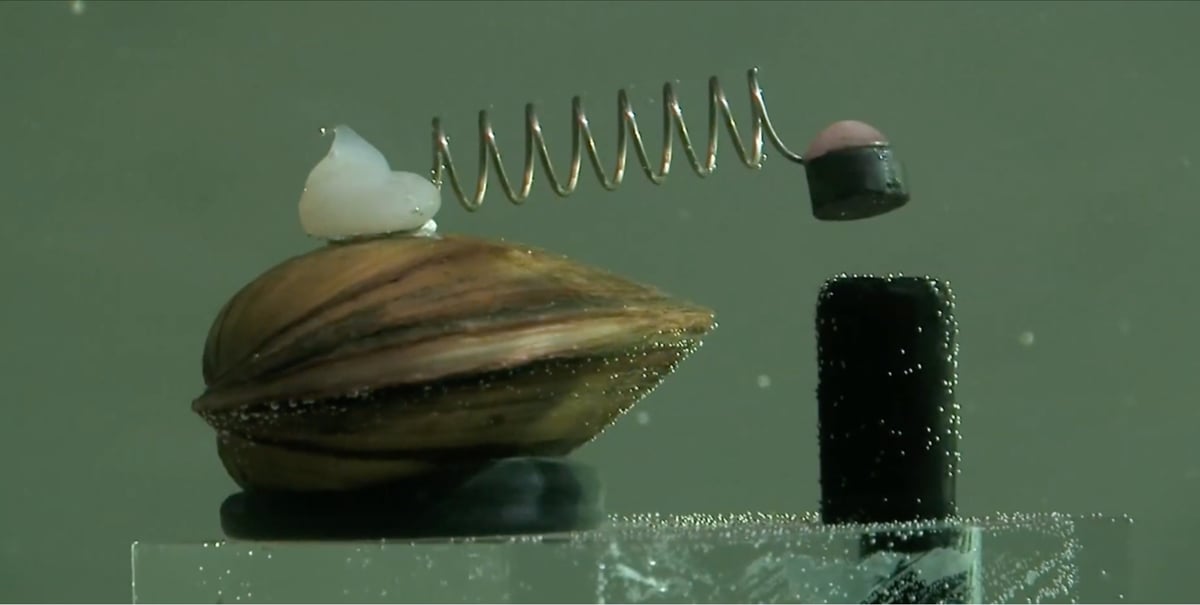

In the city of Poznań, Poland, a group of eight clams controls the local water supply through a clever bio-monitoring system:

These biological systems are comprised of eight mussels with sensors hot-glued to their shells. They work together with a network of computers and have been given control over the city’s water supply. If the waters are clean, these mussels stay open and happy. But when water quality drops too low, they close off and shut the water supply of millions of people with them.

According to The Economist (archive), more than 50 such systems are now deployed in Poland and Russia to help protect water supplies:

The system is nifty. When the molluscs encounter heavy metals, pesticides or other pollutants, they close their shells, explains Piotr Domek of Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznan, who has worked on the project for three decades. To create a natural early-warning system, Mr Domek and his colleagues collect the clams from rivers or reservoirs, and attach a coil and a magnet to their shells. Computers register whether their shells are open or closed by detecting changes in the magnetic field.

“In the case of a terrorist attack, an ecological disaster or another contamination of the water supply, the clams will close,” says Mr Domek. This, in turn, will automatically cut off the water supply. The clams, he thinks, are life-savers. “If contaminated water goes straight to our taps, we will get poisoned,” he says in “Fat Kathy”, a short film that celebrates the invaluable bivalves.

You can watch that short film here:

Each clam serves a tour of duty of a few months:

Each worker mussel spends three months on duty — after that, they become too accustomed to their new surroundings and are no longer sensitive enough to properly monitor the water. For retirement, they are gently tossed back where they came from.

Tags: video