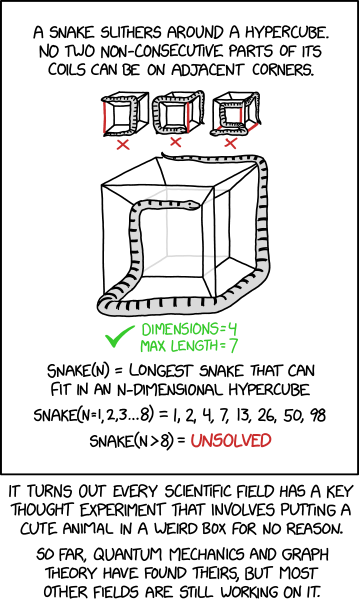

A path of length 98 was published in 2009 and proven by exhaustive search in 2015. Some known lower bounds are collected in https://arxiv.org/pdf/1603.05119. f(9) >= 190.

The "snake and box wiki" formerly at http://ai1.ai.uga.edu/sib/sibwiki/ is no longer online. The last snapshot from archive.org: https://web.archive.org/web/20200217135138/http://ai1.ai.uga.edu/sib/sibwiki/doku.php/records

Jason Hickel and Dylan Sullivan

Over the past two decades, the posture of the United States toward China has evolved from economic cooperation to outright antagonism. US media outlets and politicians have engaged in persistent anti-China rhetoric, while the US government has imposed trade restrictions and sanctions on China and pursued military buildup close to Chinese territory. Washington wants people to believe that China poses a threat.

China’s rise indeed threatens US interests, but not in the way the US political elite seeks to frame it.

The US relationship with China needs to be understood in the context of the capitalist world-system. Capital accumulation in the core states, often glossed as the “Global North”, depends on cheap labour and cheap resources from the periphery and semi-periphery, the so-called “Global South”.

This arrangement is crucial to ensuring high profits for the multinational firms that dominate global supply chains. The systematic price disparity between the core and periphery also enables the core to achieve a large net-appropriation of value from the periphery through unequal exchange in international trade.

Ever since the 1980s, when China opened up to Western investment and trade, it has been a crucial part of this arrangement, providing a major source of labour for Western firms – labour that is cheap but also highly skilled and highly productive. For instance, much of Apple’s production relies on Chinese labour. According to research by the economist Donald A Clelland, if Apple had to pay Chinese and East Asian workers at the same rate as a US worker, this would have cost them an additional $572 per iPad in 2011.

But over the past two decades, wages in China have increased quite dramatically. Around 2005 the manufacturing labour cost per hour in China was lower than in India, less than $1 per hour. In the years since, China’s hourly labour costs have increased to over $8 per hour, while India’s are now only about $2 per hour. Indeed, wages in China are now higher than in every other developing country in Asia. This a major, historical development.

This has happened for several key reasons. For one, surplus labour in China has been increasingly absorbed into the wage-labour economy, which has amplified workers’ bargaining power. At the same time, the current leadership of Xi Jinping has expanded the role of the state in China’s economy, strengthening public provisioning systems – including public healthcare and public housing – that have further improved the position of workers.

These are positive changes for China – and specifically for Chinese workers – but they pose a severe problem for Western capital. Higher wages in China impose a constraint on the profits of Western firms which operate there or which depend on Chinese manufacturing for intermediate parts and other key inputs.

The other problem, for the core states, is that the increase in China’s wages and prices is reducing its exposure to unequal exchange. During the low-wage era of the 1990s, China’s export to import ratio with the core was extremely high. In other words, China had to export very large quantities of goods in order to obtain necessary imports. Today this ratio is much lower, representing a dramatic improvement in China’s terms of trade, substantially reducing the core’s ability to appropriate value from China.

Given all this, capitalists in the core states are now desperate to do something to restore their access to cheap labour and resources. One option – increasingly promoted by the Western business press – is to relocate industrial production to other parts of Asia where wages are cheaper. But this is costly in terms of lost production, the need to find new staff, and other supply chain disruptions. The other option is to force Chinese wages back down. Hence the attempts by the United States to undermine the Chinese government and destabilise the Chinese economy - including through economic warfare and the constant threat of military escalation.

Ironically, Western governments sometimes justify their opposition to China on the grounds that China’s exports are too cheap. It is often claimed that China “cheats” in international trade, by artificially suppressing the exchange rate for its currency, the renminbi. The problem with this argument, however, is that China abandoned this policy around a decade ago. As the economist Jose Antonio Ocampo noted in 2017, “in recent years, China has rather been making efforts to avoid a depreciation of the renminbi, sacrificing a large amount of reserves. This may imply that, if anything, this currency is now overvalued.” China did eventually permit a devaluation in 2019, when tariffs imposed by the Trump administrated increased pressure on the renminbi. But this was a normal response to a change in market conditions, not an attempt to suppress the renminbi below its market rate.

The United States largely supported the Chinese government in the period when its currency was undervalued, including through loans from the IMF and World Bank. The West turned decisively against China in the mid-2010s, at precisely the moment when the country began to raise its prices and challenge its position as a peripheral supplier of cheap inputs to Western-dominated supply chains.

The second element that’s driving US hostility toward China is technology. Beijing has used industrial policy to prioritise technological development in strategic sectors over the past decade, and has achieved remarkable progress. It now has the world’s largest high-speed rail network, manufactures its own commercial aircraft, leads the world on renewable energy technology and electric vehicles, and enjoys advanced medical technology, smartphone technology, microchip production, artificial intelligence, etc. The tech news coming out of China has been dizzying. These are achievements that we only expect from high-income countries, and China is doing it with almost 80 percent less GDP per capita than the average “advanced economy”. It is unprecedented.

This poses a problem for the core states because one of the main pillars of the imperial arrangement is that they need to maintain a monopoly over necessary technologies like capital goods, medicines, computers, aircraft and so on. This forces the “Global South” into a position of dependency, so they are forced to export large quantities of their cheapened resources in order to obtain these necessary technologies. This is what sustains the core’s net-appropriation through unequal exchange

China’s technological development is now breaking Western monopolies, and may give other developing countries alternative suppliers for necessary goods at more affordable prices. This poses a fundamental challenge to the imperial arrangement and unequal exchange.

The US has responded by imposing sanctions designed to cripple China’s technological development. So far this has not worked; if anything, it has increased incentives for China to develop sovereign technological capacities. With this weapon mostly neutralised, the US wants to resort to warmongering, the main objective of which would be to destroy China’s industrial base, and divert China’s investment capital and productive capacities toward defence. The US wants to go to war with China not because China poses some kind of military threat to the American people, but because Chinese development undermines the interests of imperial capital.

Western claims about China posing some kind of military threat are pure propaganda. The material facts tell a fundamentally different story. In fact, China’s military spending per capita is less than the global average, and 1/10th that of the US alone. Yes, China has a big population, but even in absolute terms, the US-aligned military bloc spends over seven times more on military power than China does. The US controls eight nuclear weapons for every one that China has.

China may have the power to prevent the US from imposing its will on it, but it does not have the power to impose its will on the rest of the world in the way that the core states do. The narrative that China poses some kind of military threat is wildly overblown.

In fact, the opposite is true. The US has hundreds of military bases and facilities around the world. A significant number of them are stationed near China – in Japan and South Korea. By contrast, China has only one foreign military base, in Djibouti, and zero military bases near US borders.

Furthermore, China has not fired a single bullet in international warfare in over 40 years, while during this time the US has invaded, bombed or carried out regime-change operations in over a dozen Global South countries. If there is any state that poses a known threat to world peace and security, it is the US.

The real reason for Western warmongering is because China is achieving sovereign development and this is undermining the imperial arrangement on which Western capital accumulation depends. The West will not let global economic power slip from its hands so easily.

This article was originally published by Al Jazeera English. We have reproduced it here so that readers can access all underlying sources.

The index is the search bar, the random access to the facts we can look up.

The table of contents, though, that’s a point of view. It’s a taxonomy of how to understand a complicated idea. It’s the skeleton of the narrative and the pedagogy for learning.

We’re at risk of becoming all index.

The world could probably benefit from your table of contents.

If you’ve ever wondered why the economy feels stuck, even when it seems like there’s a lot more money in the system, this episode will blow your mind.

Political economist Ann Pettifor joins Nick and Goldy to explain why money isn’t flowing like it used to, and why that matters. Over the last century, the velocity of money (how quickly a dollar circulates) has plummeted. Today, each dollar in circulation generates up to 70% less economic activity than it did just ten years ago, so it’s not being circulated through the local economies, growing wages and building small businesses with each transaction. Instead, new dollars are just frozen in place.

The culprit? Excess money sitting at the top—hoarded by the wealthy and corporations instead of getting spent.

Pettifor shows that taxing the rich isn’t just fair—it’s pro-growth. Redistribution accelerates the velocity of money, unleashing demand, expanding markets, creating jobs, and ultimately boosting prosperity for everyone. If you’re ready to reclaim the economy from its top-down chokehold, this back-to-basics episode isn’t optional—it’s essential.

Ann Pettifor is a British political economist, author, and Director of Policy Research in Macroeconomics (PRIME). Known for correctly predicting the 2008 financial crisis, her work spans sovereign debt, macroeconomics, and sustainable development. She’s the author of The Production of Money and The Case for the Green New Deal, and directs groundbreaking research that puts money creation and equitable growth at the center of economic policy.

Social Media:

Further reading:

Want to expand the economy? Tax the rich!

What does money velocity tell us about low inflation in the U.S.?

REPORT: A world awash in money

Vultures are Circling Our Fragile Economy

The Case for the Green New Deal

Website: http://pitchforkeconomics.com

Instagram: @pitchforkeconomics

Threads: pitchforkeconomics

Bluesky: @pitchforkeconomics.bsky.social

TikTok: @pitchfork_econ

Twitter: @PitchforkEcon, @NickHanauer, @civicaction

YouTube: @pitchforkeconomics

LinkedIn: Pitchfork Economics

Substack: The Pitch

The post Back to Basics Series: The Velocity of Money (with Ann Pettifor) appeared first on Pitchfork Economics.

Download audio: https://www.pitchforkeconomics.com/download-episode/4654/back-to-basics-series-the-velocity-of-money-with-ann-pettifor.mp3?ref=feed

Wikipedia editors just adopted a new policy to help them deal with the slew of AI-generated articles flooding the online encyclopedia. The new policy, which gives an administrator the authority to quickly delete an AI-generated article that meets a certain criteria, isn’t only important to Wikipedia, but also an important example for how to deal with the growing AI slop problem from a platform that has so far managed to withstand various forms of enshittification that have plagued the rest of the internet.

Wikipedia is maintained by a global, collaborative community of volunteer contributors and editors, and part of the reason it remains a reliable source of information is that this community takes a lot of time to discuss, deliberate, and argue about everything that happens on the platform, be it changes to individual articles or the policies that govern how those changes are made. It is normal for entire Wikipedia articles to be deleted, but the main process for deletion usually requires a week-long discussion phase during which Wikipedians try to come to consensus on whether to delete the article.

However, in order to deal with common problems that clearly violate Wikipedia’s policies, Wikipedia also has a “speedy deletion” process, where one person flags an article, an administrator checks if it meets certain conditions, and then deletes the article without the discussion period.

For example, articles composed entirely of gibberish, meaningless text, or what Wikipedia calls “patent nonsense,” can be flagged for speedy deletion. The same is true for articles that are just advertisements with no encyclopedic value. If someone flags an article for deletion because it is “most likely not notable,” that is a more subjective evaluation that requires a full discussion.

At the moment, most articles that Wikipedia editors flag as being AI-generated fall into the latter category because editors can’t be absolutely certain that they were AI-generated. Ilyas Lebleu, a founding member of WikiProject AI Cleanup and an editor that contributed some critical language in the recently adopted policy on AI generated articles and speedy deletion, told me that this is why previous proposals on regulating AI generated articles on Wikipedia have struggled.

“While it can be easy to spot hints that something is AI-generated (wording choices, em-dashes, bullet lists with bolded headers, ...), these tells are usually not so clear-cut, and we don't want to mistakenly delete something just because it sounds like AI,” Lebleu told me in an email. “In general, the rise of easy-to-generate AI content has been described as an ‘existential threat’ to Wikipedia: as our processes are geared towards (often long) discussions and consensus-building, the ability to quickly generate a lot of bogus content is problematic if we don't have a way to delete it just as quickly. Of course, AI content is not uniquely bad, and humans are perfectly capable of writing bad content too, but certainly not at the same rate. Our tools were made for a completely different scale.”

The solution Wikipedians came up with is to allow the speedy deletion of clearly AI-generated articles that broadly meet two conditions. The first is if the article includes “communication intended for the user.” This refers to language in the article that is clearly an LLM responding to a user prompt, like "Here is your Wikipedia article on…,” “Up to my last training update …,” and "as a large language model.” This is a clear tell that the article was generated by an LLM, and a method we’ve previously used to identify AI-generated social media posts and scientific papers.

Lebleu, who told me they’ve seen these tells “quite a few times,” said that more importantly, they indicate the user hasn’t even read the article they’re submitting.

“If the user hasn't checked for these basic things, we can safely assume that they haven't reviewed anything of what they copy-pasted, and that it is about as useful as white noise,” they said.

The other condition that would make an AI-generated article eligible for speedy deletion is if its citations are clearly wrong, another type of error LLMs are prone to. This can include both the inclusion of external links for books, articles, or scientific papers that don’t exist and don’t resolve, or links that lead to completely unrelated content. Wikipedia's new policy gives the example of “a paper on a beetle species being cited for a computer science article.”

Lebleu said that speedy deletion is a “band-aid” that can take care of the most obvious cases and that the AI problem will persist as they see a lot more AI-generated content that doesn’t meet these new conditions for speedy deletion. They also noted that AI can be a useful tool that could be a positive force for Wikipedia in the future.

“However, the present situation is very different, and speculation on how the technology might develop in the coming years can easily distract us from solving issues we are facing now, they said. “A key pillar of Wikipedia is that we have no firm rules, and any decisions we take today can be revisited in a few years when the technology evolves.”

Lebleu said that ultimately the new policy leaves Wikipedia in a better position than before, but not a perfect one.

“The good news (beyond the speedy deletion thing itself) is that we have, formally, made a statement on LLM-generated articles. This has been a controversial aspect in the community before: while the vast majority of us are opposed to AI content, exactly how to deal with it has been a point of contention, and early attempts at wide-ranging policies had failed. Here, building up on the previous incremental wins on AI images, drafts, and discussion comments, we workshopped a much more specific criterion, which nonetheless clearly states that unreviewed LLM content is not compatible in spirit with Wikipedia.”