Today's links

- When AI prophecy fails: Hating workers is a hell of a drug.

- Hey look at this: Delights to delectate.

- Object permanence: SCOTUS lets the FBI kidnap Americans; Inequality perverts justice; Free the McFlurry!

- Upcoming appearances: Where to find me.

- Recent appearances: Where I've been.

- Latest books: You keep readin' em, I'll keep writin' 'em.

- Upcoming books: Like I said, I'll keep writin' 'em.

- Colophon: All the rest.

When AI prophecy fails (permalink)

Amazon made $35 billion in profit last year, so they're celebrating by laying off 14,000 workers (a number they say will rise to 30,000). This is the kind of thing that Wall Street loves, and this layoff comes after a string of pronouncements from Amazon CEO Andy Jassy about how AI is going to let them fire tons of workers.

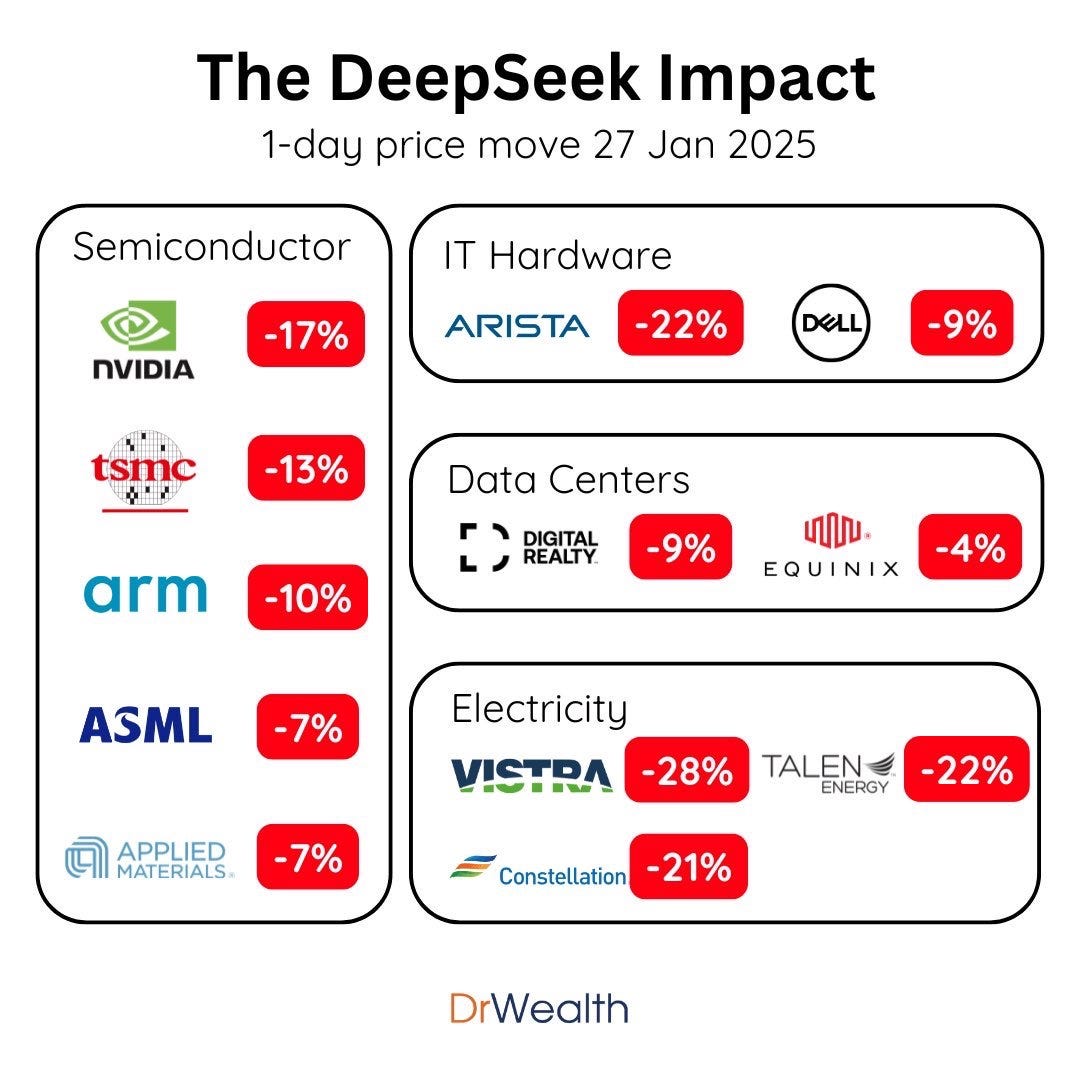

That's the AI story, after all. It's not about making workers more productive or creative. The only way to recoup the $700 billion in capital expenditure to date (to say nothing of AI companies' rather fanciful coming capex commitments) is by displacing workers – a lot of workers. Bain & Co say the sector needs to be grossing $2 trillion by 2030 in order to break even, which is more than the combined grosses of Amazon, Google, Microsoft, Apple Nvidia and Meta:

Every investor who has put a nickel into that $700b capex is counting on bosses firing a lot of workers and replacing them with AI. Amazon is also counting on people buying a lot of AI from it after firing those workers. The company has sunk $120b into AI this year alone.

There's just one problem: AI can't do our jobs. Oh, sure, an AI salesman can convince your boss to fire you and replace you with an AI that can't do your job, but that's the world's easiest sales-call. Your boss is relentlessly horny for firing you:

https://pluralistic.net/2025/03/18/asbestos-in-the-walls/#government-by-spicy-autocomplete

But there's a lot of AI buyers' remorse. 95% of AI deployments have either produced no return on capital, or have been money-losing:

AI has "no significant impact on workers’ earnings, recorded hours, or wages":

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5219933

What's Amazon to do? How do they convince you to buy enough AI to justify that $180b in capital expenditure? Somehow, they have to convince you that an AI can do your workers' jobs. One way to sell that pitch is to fire a ton of Amazon workers and announce that their jobs have been given to a chatbot. This isn't a production strategy, it's a marketing strategy – it's Amazon deliberately taking an efficiency loss by firing workers in a desperate bid to convince you that you can fire your workers:

https://pluralistic.net/2025/08/05/ex-princes-of-labor/#hyper-criti-hype

Amazon does use a lot of AI in its production, of course. AI is the "digital whip" that Amazon uses to allow itself to control drivers who (nominally) work for subcontractors. This lets Amazon force workers into unsafe labor practices that endanger them and the people they share the roads with, while offloading responsibility onto "independent delivery service" operators and the drivers themselves:

https://pluralistic.net/2025/10/23/traveling-salesman-solution/#pee-bottles

Amazon leadership has announced that AI has or will shortly replace its coders as well. But chatbots can't do software engineering – sure, they can write code, but writing code is only a small part of software engineering. An engineer's job is to maintain a very deep and wide context window, one that considers how each piece of code interacts with the software that executes before it and after it, and with the systems that feed into it and accept its output.

There's one thing AI struggles with beyond all else: maintaining context. Each linear increase in context that you demand from AI results in an exponential increase in computational expense. AI has no object permanence. It doesn't know where it's been and it doesn't know where it's going. It can't remember how many fingers it's drawn, so it doesn't know when to stop. It can write a routine, but it can't engineer a system.

When tech bosses dream of firing coders and replacing them with AI, they're fantasizing about getting rid of their highest-paid, most self-assured workers and transforming the insecure junior programmers leftover into AI babysitters whose job it is to evaluate and integrate that code at a speed that no one – much less a junior programmer – can meet if they are to do a careful and competent job:

https://www.bloodinthemachine.com/p/how-ai-is-killing-jobs-in-the-tech-f39

The jobs that can be replaced with AI are the jobs that companies already gave up on doing well. If you've already outsourced your customer service to an overseas call-center whose workers are not empowered to solve any of your customers' problems, why not fire those workers and replace them with chatbots? The chatbots also can't solve anyone's problems, and they're even cheaper than overseas call-center workers:

https://pluralistic.net/2025/08/06/unmerchantable-substitute-goods/#customer-disservice

Amazon CEO Andy Jassy wrote that he "is convinced" that firing workers will make the company "AI ready," but it's not clear what he means by that. Does he mean that the mass firings will save money while maintaining quality, or that mass firings will help Amazon recoup the $180,000,000,000 it spent on AI this year?

Bosses really want AI to work, because they really, really want to fire you. As Allison Morrow writes for CNN bosses are firing workers in anticipation of the savings AI will produce…someday:

https://www.cnn.com/2025/10/28/business/what-amazons-mass-layoffs-are-really-about

All this can feel improbable. Would bosses really fire workers on the promise of eventual AI replacements, leaving themselves with big bills for AI and falling revenues as the absence of those workers is felt?

The answer is a resounding yes. The AI industry has done such a good job of convincing bosses that AI can do their workers' jobs that each boss for whom AI fails assumes that they've done something wrong. This is a familiar dynamic in con-jobs.

The people who get sucked into pyramid schemes all think that they are the only ones failing to sell any of the "merchandise" they shell out every month to buy, and that no one else has a garage full of unsold leggings or essential oils. They don't know that, to a first approximation, the MLM industry has no sales, and relies entirely on "entrepreneurs" lying to themselves and one another about the demand for their wares, paying out of their own pocket for goods that no one wants.

The MLM industry doesn't just rely on this deception – they capitalize on it, by selling those self-flagellating "entrepreneurs" all kinds of expensive training courses that promise to help them overcome the personal defects that stop them from doing as well as all those desperate liars boasting about their incredible MLM sales success:

https://pluralistic.net/2025/05/05/free-enterprise-system/#amway-or-the-highway

The AI industry has its own version of those sales coaching courses – there's a whole secondary industry of management consultancies and business schools offering high-ticket "continuing education" courses to bosses who think that the only reason the AI they've purchased isn't saving them money is that they're doing AI wrong.

Amazon really needs AI to work. Last week, Ed Zitron published an extensive analysis of leaked documents showing how much Amazon is making from AI companies who are buying cloud services from it. His conclusion? Take away AI and Amazon's cloud division is in steep decline:

https://www.wheresyoured.at/costs/

What's more, those big-money AI customers – like Anthropic – are losing tens of billions of dollars per year, relying on investors to keep handing them money to incinerate. Amazon needs bosses to believe they can fire workers and replace them with AI, because that way, investors will keep giving Anthropic the money it needs to keep Amazon in the black.

Amazon firing 30,000 workers in the run-up to Christmas is a great milestone in enshittification. America's K-shaped recovery means that nearly all of the consumption is coming from the wealthiest American households, and these households overwhelmingly subscribe to Prime. Prime-subscribing households do not comparison shop. After all, they've already prepaid for a year's shipping in advance. These households start and end nearly every shopping trip in the Amazon app.

If Amazon fires 30,000 workers and tanks its logistics network and e-commerce systems, if it allows itself to drown in spam and scam reviews, if it misses its delivery windows and messes up its returns, that will be our problem, not Amazon's. In a world of commerce where Amazon's predatory pricing, lock-in, and serial acquisitions has left us with few alternatives, Amazon can truly be "too big to care":

https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2025/oct/05/way-past-its-prime-how-did-amazon-get-so-rubbish

From that enviable position, Amazon can afford to enshittify its services in order to sell the big AI lie. Killing 30,000 jobs is a small price to pay if it buys them a few months before a reckoning for its wild AI overspending, keeping the AI grift alive for just a little longer.

(Image: Cryteria, CC BY 3.0, modified)

Hey look at this (permalink)

- Eugene Debs and All Of Us https://www.hamiltonnolan.com/p/eugene-debs-and-all-of-us

-

US Business Cycles 1954-2020 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vXRC3RrngcI

-

Ed Zitron Gets Paid to Love AI. He Also Gets Paid to Hate AI https://www.wired.com/story/ai-pr-ed-zitron-profile/

-

Worried About AI Monopoly? Embrace Copyright’s Limits https://www.lawfaremedia.org/article/worried-about-ai-monopoly–embrace-copyright-s-limits

Object permanence (permalink)

#10yrsago Librarian of Congress puts impossible conditions on your right to jailbreak your 3D printer https://michaelweinberg.org/post/132021560865/unlocking-3d-printers-ruling-is-a-mess

#10yrsago The two brilliant, prescient 20th century science fiction novels you should read this election season https://memex.craphound.com/2015/10/28/the-two-brilliant-prescient-20th-century-science-fiction-novels-you-should-read-this-election-season/

#10yrsago Hundreds of city police license plate cams are insecure and can be watched by anyone https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2015/10/license-plate-readers-exposed-how-public-safety-agencies-responded-massive

#10yrsago Appeals court holds the FBI is allowed to kidnap and torture Americans outside US borders https://www.techdirt.com/2015/10/28/court-your-fourth-fifth-amendment-rights-no-longer-exist-if-you-leave-country/

#10yrsago South Carolina sheriff fires the school-cop who beat up a black girl at her desk https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2015/oct/28/south-carolina-parents-speak-out-school-board

#10yrsago The more unequal your society is, the more your laws will favor the rich https://web.archive.org/web/20151028133814/http://america.aljazeera.com/opinions/2015/10/the-more-unequal-the-country-the-more-the-rich-rule.html

#5yrsago Trump abandons supporters to freeze https://pluralistic.net/2020/10/28/trumpcicles/#omaha

#5yrsago RIAA's war on youtube-dl https://pluralistic.net/2020/10/28/trumpcicles/#yt-dl

#1yrago The US Copyright Office frees the McFlurry https://pluralistic.net/2024/10/28/mcbroken/#my-milkshake-brings-all-the-lawyers-to-the-yard

Upcoming appearances (permalink)

- Miami: Enshittification at Books & Books, Nov 5

https://www.eventbrite.com/e/an-evening-with-cory-doctorow-tickets-1504647263469 -

Miami: Cloudfest, Nov 6

https://www.cloudfest.com/usa/ -

Burbank: Burbank Book Festival, Nov 8

https://www.burbankbookfestival.com/ -

Lisbon: A post-American, enshittification-resistant internet, with Rabble (Web Summit), Nov 12

https://websummit.com/sessions/lis25/92f47bc9-ca60-4997-bef3-006735b1f9c5/a-post-american-enshittification-resistant-internet/ -

Cardiff: Hay Festival After Hours, Nov 13

https://www.hayfestival.com/c-203-hay-festival-after-hours.aspx -

Oxford: Enshittification and Extraction: The Internet Sucks Now with Tim Wu (Oxford Internet Institute), Nov 14

https://www.oii.ox.ac.uk/news-events/events/enshittification-and-extraction-the-internet-sucks-now/ -

London: Enshittification with Sarah Wynn-Williams and Chris Morris, Nov 15

https://www.barbican.org.uk/whats-on/2025/event/cory-doctorow-with-sarah-wynn-williams -

London: Downstream IRL with Aaron Bastani (Novara Media), Nov 17

https://dice.fm/partner/tickets/event/oen5rr-downstream-irl-aaron-bastani-in-conversation-with-cory-doctorow-17th-nov-earth-london-tickets -

London: Enshittification with Carole Cadwalladr (Frontline Club), Nov 18

https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/e/in-conversation-enshittification-tickets-1785553983029 -

Virtual: Enshittification with Vass Bednar (Vancouver Public Library), Nov 21

https://www.crowdcast.io/@bclibraries-present -

Seattle: Neuroscience, AI and Society (University of Washington), Dec 4

https://compneuro.washington.edu/news-and-events/neuroscience-ai-and-society/ -

Madison, CT: Enshittification at RJ Julia, Dec 8

https://rjjulia.com/event/2025-12-08/cory-doctorow-enshittification

Recent appearances (permalink)

- Enshittification and the Rot Economy with Ed Zitron (Clarion West)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Tz71pIWbFyc -

Amanpour & Co (New Yorker Radio Hour)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I8l1uSb0LZg -

Enshittification is Not Inevitable (Team Human)

https://www.teamhuman.fm/episodes/339-cory-doctorow-enshittification-is-not-inevitable -

The Great Enshittening (The Gray Area)

https://www.reddit.com/r/philosophypodcasts/comments/1obghu7/the_gray_area_the_great_enshittening_10202025/ -

Enshittification (Smart Cookies)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-BoORwEPlQ0

Latest books (permalink)

- "Canny Valley": A limited edition collection of the collages I create for Pluralistic, self-published, September 2025

-

"Enshittification: Why Everything Suddenly Got Worse and What to Do About It," Farrar, Straus, Giroux, October 7 2025

https://us.macmillan.com/books/9780374619329/enshittification/ -

"Picks and Shovels": a sequel to "Red Team Blues," about the heroic era of the PC, Tor Books (US), Head of Zeus (UK), February 2025 (https://us.macmillan.com/books/9781250865908/picksandshovels).

-

"The Bezzle": a sequel to "Red Team Blues," about prison-tech and other grifts, Tor Books (US), Head of Zeus (UK), February 2024 (the-bezzle.org).

-

"The Lost Cause:" a solarpunk novel of hope in the climate emergency, Tor Books (US), Head of Zeus (UK), November 2023 (http://lost-cause.org).

-

"The Internet Con": A nonfiction book about interoperability and Big Tech (Verso) September 2023 (http://seizethemeansofcomputation.org). Signed copies at Book Soup (https://www.booksoup.com/book/9781804291245).

-

"Red Team Blues": "A grabby, compulsive thriller that will leave you knowing more about how the world works than you did before." Tor Books http://redteamblues.com.

-

"Chokepoint Capitalism: How to Beat Big Tech, Tame Big Content, and Get Artists Paid, with Rebecca Giblin", on how to unrig the markets for creative labor, Beacon Press/Scribe 2022 https://chokepointcapitalism.com

Upcoming books (permalink)

- "Unauthorized Bread": a middle-grades graphic novel adapted from my novella about refugees, toasters and DRM, FirstSecond, 2026

-

"Enshittification, Why Everything Suddenly Got Worse and What to Do About It" (the graphic novel), Firstsecond, 2026

-

"The Memex Method," Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 2026

-

"The Reverse-Centaur's Guide to AI," a short book about being a better AI critic, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2026

Colophon (permalink)

Today's top sources:

Currently writing:

- "The Reverse Centaur's Guide to AI," a short book for Farrar, Straus and Giroux about being an effective AI critic. FIRST DRAFT COMPLETE AND SUBMITTED.

-

A Little Brother short story about DIY insulin PLANNING

This work – excluding any serialized fiction – is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license. That means you can use it any way you like, including commercially, provided that you attribute it to me, Cory Doctorow, and include a link to pluralistic.net.

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Quotations and images are not included in this license; they are included either under a limitation or exception to copyright, or on the basis of a separate license. Please exercise caution.

How to get Pluralistic:

Blog (no ads, tracking, or data-collection):

Newsletter (no ads, tracking, or data-collection):

https://pluralistic.net/plura-list

Mastodon (no ads, tracking, or data-collection):

Medium (no ads, paywalled):

Twitter (mass-scale, unrestricted, third-party surveillance and advertising):

Tumblr (mass-scale, unrestricted, third-party surveillance and advertising):

https://mostlysignssomeportents.tumblr.com/tagged/pluralistic

"When life gives you SARS, you make sarsaparilla" -Joey "Accordion Guy" DeVilla

READ CAREFULLY: By reading this, you agree, on behalf of your employer, to release me from all obligations and waivers arising from any and all NON-NEGOTIATED agreements, licenses, terms-of-service, shrinkwrap, clickwrap, browsewrap, confidentiality, non-disclosure, non-compete and acceptable use policies ("BOGUS AGREEMENTS") that I have entered into with your employer, its partners, licensors, agents and assigns, in perpetuity, without prejudice to my ongoing rights and privileges. You further represent that you have the authority to release me from any BOGUS AGREEMENTS on behalf of your employer.

ISSN: 3066-764X