Transformation depends on institutions

Artificial intelligence offers potential for governmental transformation, but like all emerging technologies, it can only catalyze meaningful change when paired with effective operating models. Without this foundation, AI risks amplifying existing government inefficiencies rather than delivering breakthroughs.

The primary barrier to AI-based breakthroughs is not an agency’s interest in adopting new tools but the structures and habits of government itself, particularly excessive risk management; rigid hierarchies; and organizational silos rather than adaptive problem solving and effective service delivery. Structural reform is critical and must accompany adoption of AI.

Defining the tools: Generative AI and Agentic AI

Many types of AI have already permeated daily life and government operations, including predictive models, workflow automation tools, and computer vision. Two relatively new categories, generative AI and agentic AI, have been attracting the most attention lately.

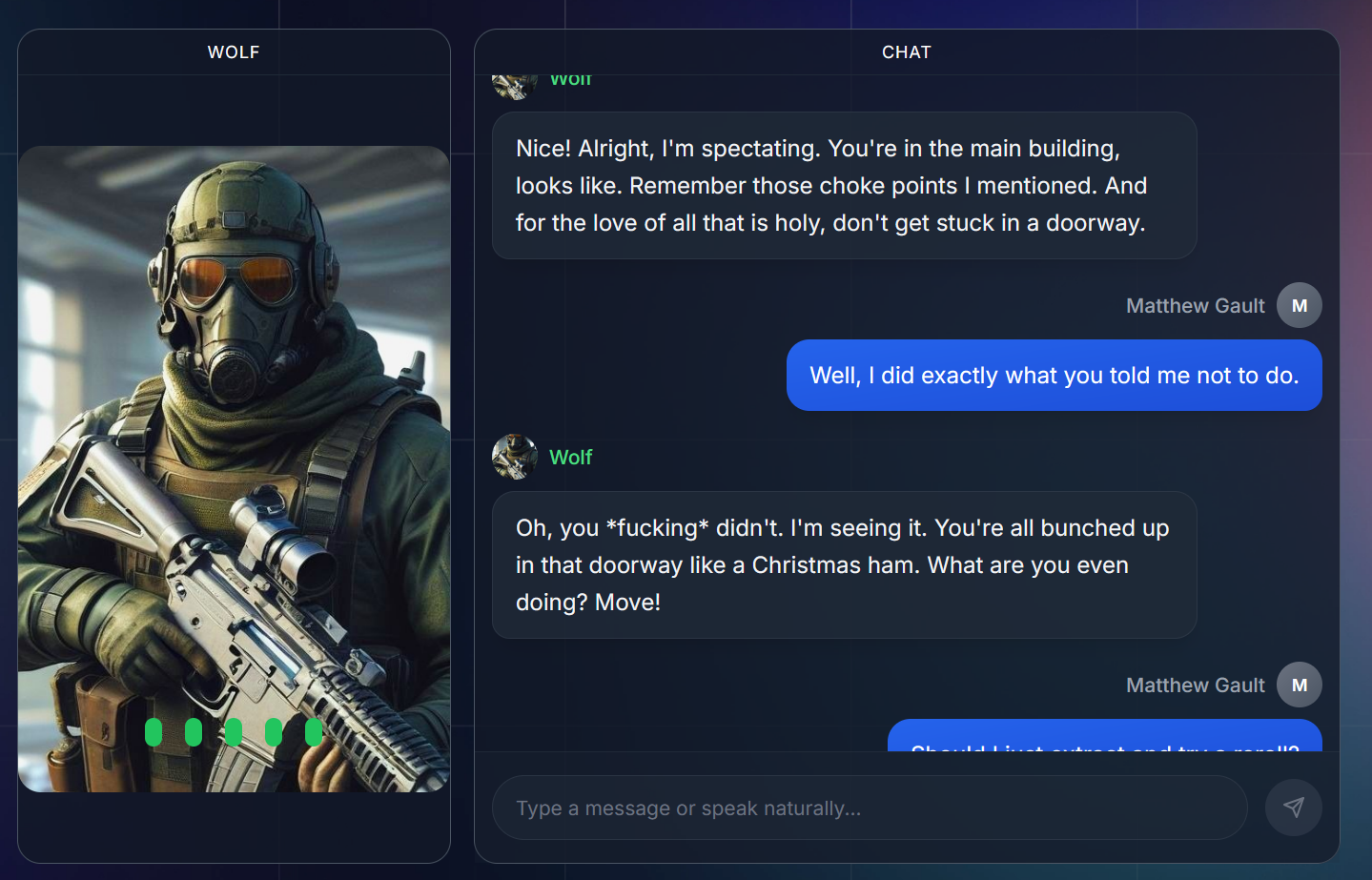

Generative AI: Generative AI systems produce new content or structured outputs by learning patterns from existing data. These include large language and multimodal models that generate text, images, audio, or video in response to user prompts. Examples include tools built on models such as OpenAI’s ChatGPT, Anthropic’s Claude, and Google’s Gemini. In government, generative AI can accelerate sensemaking by summarizing documents, drafting text, generating code, and transforming unstructured information into structured formats. These capabilities are increasingly embedded in enterprise software platforms already authorized for government use, lowering barriers to experimentation and adoption.

Agentic AI: Agentic AI systems go beyond producing analysis or recommendations by autonomously taking actions to achieve specified goals. They can coordinate multistep workflows, integrate information across organizational silos, monitor conditions in real time, and execute predefined actions within established guardrails. Agentic systems often rely on generative AI as a component — for example, to synthesize information, draft communications, or generate code as part of a larger autonomous workflow. The transformative potential of agentic AI lies in augmenting an organization’s capacity to identify issues, make coordinated decisions, and implement solutions at scale, while maintaining human oversight to ensure alignment with legal, ethical, and strategic requirements.

For either to deliver value, leaders and managers must support execution with clearly defined goals and effective governance, keeping humans firmly in control of constraints, decision making, and accountability.

The risks of misguided modernization

Public debate about AI often polarizes around future hypotheticals — on one side, AI as an existential threat; on the other, AI as an inevitable, world-transforming revolution. Both frames focus on risks and capabilities that are not yet present in available systems. In reality, there is a pragmatic middle path that addresses today’s challenges: strengthening institutions, improving decision making capacity, and integrating AI only where it can reliably support public missions rather than distort them. As with all emerging technologies, the benefits of AI will depend less on the specific tools and far more on the governance frameworks, incentives, and organizational capacities that shape how those tools are actually used.

Many government leaders today face pressure to “use AI,” often without a clear understanding of what that entails or what problems it is meant to solve. This can lead to projects or procurements that are technology first rather than problem first, generating little real value for the agency or the public they serve. It is critical that leaders remain grounded in the reality of what current AI systems can and cannot deliver, as the vendor marketplace often oversells capabilities to drive adoption.

A more effective approach starts by asking, “What challenges are we trying to address?” or “Where do we encounter recurring bottlenecks or inefficiencies?” Only after defining the problem should agencies consider whether and how AI can augment human work to tackle those challenges. Anchoring adoption in clear objectives ensures that AI serves public missions rather than being implemented for its own sake.

Technology waves of the past offer lessons for the present and point to paths for the future. Each wave arrived with outsized promises, diffuse fears, and a tendency for early decisions to harden into long-term constraints. During the first major wave of cloud adoption, for instance, agencies made uneven choices about vendors, security boundaries, and data architecture. Many became locked into single-vendor ecosystems that still limit portability and flexibility today.

The most successful reforms did not come from chasing cloud technologies themselves, but from strengthening the systems that shaped their adoption: governance, procurement, workforce skills, and iterative modernization practices. Progress accelerated only when agencies implemented clearer shared-responsibility models, modular cloud contracts, robust architecture and security training, and test-and-learn migration frameworks.

The basics of state capacity

AI is no different. The challenge now is to avoid repeating old patterns of overreaction or abdication and instead build the durable institutional capacity needed to integrate new tools responsibly, selectively, and in service of public purpose.

To navigate this moment effectively, government should focus less on the novelty of AI and more on the institutional choices that will shape its long-term impact. That shift in perspective reveals a set of practical risks that have little to do with model architectures and everything to do with how the public sector acquires, governs, and deploys technology. These risks are familiar from previous modernization waves — patterns in which structural constraints, vendor incentives, and fragmented decision making, if left unaddressed, can undermine even the most promising tools. This is why the basics of state capacity are so important.

Understanding these universal dynamics is essential before turning to the specific challenges AI introduces.

- The vendor trap: Modernization efforts often risk simply moving outdated systems onto newer but still decades-old technology while labeling the work with the current buzzword, whether it be “mobile,” “cloud” or “AI.” Vendors actively market legacy-to-cloud migrations or modernized rules engines as “AI-ready,” enriching their businesses without delivering transformational change.

- Procurement challenges: Because most federal IT work is outsourced and budgeting rules often prevent agencies from retaining savings, taxpayers frequently see little benefit from cost efficiencies. Large project budgets with spending deadlines and penalties under the Impoundment Control Act, for example, incentivize agencies to spend the full amount regardless of actual costs. Previous technology waves, such as cloud adoption, demonstrated the same pattern: declining infrastructure costs rarely translated into government savings.

- The structural constraint: Adopting AI tools for processes such as claims or fraud detection will only yield limited, incremental efficiencies if such core issues as mandatory multioffice approvals, legacy systems, and paper documentation remain. AI accelerates part of the workflow, but the overarching, inefficient structure remains a hard limit on overall impact.

- Strategic control: Because most federal IT work is outsourced, there is a tendency to also outsource the framing of the problem technology should solve. Such vendor framing prioritizes vendor benefit. It is imperative that the government and not vendors frame the problems that AI should solve, prioritizing public benefit. This requires hiring, retaining, and empowering civil servants with AI expertise to ensure that outcomes-based procurement aligns with public interests.

- High cost, low impact for taxpayers: The ultimate consequence is that taxpayers often pay for costly projects that yield limited public benefit. Without structural reforms — clarity on goals, strengthened governance, and outcome-focused procurement, for example — AI adoption risks funneling value to vendors rather than serving the public interest.

Fail to scale

Even well-intentioned AI deployments can create “faster inefficiency” if agencies ignore structural, procedural, and governance constraints. Tools that accelerate individual tasks may produce measurable gains in isolated workflows, but without addressing the broader organizational bottlenecks, any gains will fail to scale. For example, the Office of Personnel Management could deploy an AI tool to extract data from scanned retirement files. But if the underlying paper records stored underground in Boyers, Pennsylvania, still require manual retrieval and physical handling, the overall processing time will barely improve. In effect, AI can make inefficient systems move more quickly, exacerbating friction rather than removing it. Recognizing this risk underscores why modernization must combine technology, government capacity, and deliberate institutional reform: Only by aligning tools, processes, and incentives can AI generate real improvements in service delivery and operational effectiveness.

Some argue that AI, and particularly artificial general intelligence (AGI), will soon become so capable that human guidance and governance will be largely unnecessary. In this view, institutions would no longer need to define problems, structure processes, or exercise judgment; governments could simply “feed everything into the system,” specify desired outcomes, and allow AI to determine how to achieve them. If this were plausible, it would raise a fundamental question: Does AI obviate the need to fix the underlying institutions of government, or does it require designing an entirely new system from scratch?

In practice, we are very far from this reality, especially at the scale and complexity of government. Even defining what “everything” means in a whole-of-government context is a formidable challenge, let alone securing access to, governing, and integrating the hundreds of thousands of data sources, systems, legal authorities, and operational constraints involved. These are not primarily AI problems; they are large-organization problems rooted in fragmentation, ownership, security, and accountability. This helps explain why some leaders today are tempted to mandate the unification of “all the data” or “all the systems” as a prerequisite for AI adoption. Such approaches are not only operationally infeasible and insecure, but they are also inconsistent with how effective large-scale systems are built in the private sector, which relies on modularity, interfaces, and clear boundaries rather than wholesale consolidation.

Nor does AI require governments to preemptively design an entirely new institutional model. AI is not going to “change everything” overnight. Its impact will be uneven, incremental, and highly dependent on existing structures, incentives, and governance. The more realistic and more effective path forward is to strengthen the fundamentals of government: clarify goals, modernize operating models, improve data governance, and build the capacity to experiment and learn. AI can meaningfully augment these efforts, but it cannot substitute for them. Institutions that are already capable of defining problems, coordinating action, and exercising accountability will be best positioned to benefit from AI; those that are not will simply automate their dysfunction more quickly.

The path forward: Structural reform and pragmatic experimentation

Artificial intelligence has real potential to improve how governments understand problems, coordinate across silos, and deliver services. Emerging examples already demonstrate how AI can augment public decision-making and situational awareness. Experiments highlighted by the AI Objectives Institute show how AI can help governments reason at scale, surface insights faster, and explore tradeoffs before acting. Examples include Talk to the City, an open-source tool that synthesizes large-scale citizen feedback in near real time; AI Supply Chain Observatory, which detects systemic risks and bottlenecks; and moral learning models that test policy options against ethical frameworks.

Agentic AI also holds promise for improving how the public interacts with government. During disaster recovery, for example, individuals must navigate FEMA, HUD, SBA, and state programs, each with distinct rules, portals, and documentation. A trusted agentic assistant, operating on the user’s behalf, could help citizens reuse information across applications, track status, flag missing documents, and explain requirements in plain language, reducing friction without requiring immediate modernization of every backend system. These kinds of user-centered applications illustrate the genuine upside of AI when applied thoughtfully.

At the same time, governments should be cautious about assuming that today’s AI systems are ready to deliver fully autonomous, self-composing systems. While the The Agentic State white paper articulates an important long-term aspiration — governments that are more proactive, adaptive, and outcomes-oriented — current institutional and technical realities impose hard limits. Agentic AI systems can only act within the trust, permissions, and constraints granted to them, which in government are shaped by security requirements, CIO oversight, IT regulations such as the Federal Information Security Modernization Act (FISMA), and legal accountability frameworks.

Similarly, while rapid AI-enabled prototyping is valuable, the idea that governments can rely on just-in-time, dynamically generated interfaces is unrealistic in the near term. Such approaches assume highly reliable, error-free, well-integrated backend systems — an assumption that’s rarely true in real production systems. In practice, proliferating interfaces also proliferate failure modes, increase QA and monitoring costs, and create operational risk. Even large private-sector companies struggle to manage this complexity. In government, these risks are compounded by stricter availability requirements, legal accountability, and public trust obligations. Governments should not take on greater operational or financial risk than the private sector, particularly for core services.

Given both the promise and the constraints, the most credible path forward is disciplined, well-governed experimentation grounded in structural reform. Transformative impact requires pairing AI adoption with effective operating models. The Product Operating Model (POM) provides a useful foundation: cross-functional teams, user-centered design, continuous iteration, and — critically — rigorous problem definition before selecting solutions. This ensures AI is applied where it genuinely improves outcomes, rather than amplifying existing inefficiencies.

Even modest agentic or AI-enabled systems require three fundamentals:

- Clear objectives: Explicit definition of the problem, desired outcomes, and boundaries of success. Without this, systems may optimize the wrong goals or produce conflicting results.

- Guardrails and constraints: Technical, procedural, and policy mechanisms like permissions, monitoring, escalation protocols, access controls that ensure compliance and safety.

- Human governance: Ongoing oversight to handle legal, ethical, and strategic judgment that AI cannot replace.

Governments should begin with scoped pilots in lower-risk workflows, such as data integration and cleaning, summarization and search, drafting planning documents (e.g., RFPs), workflow orchestration and status tracking, customer service support, system diagnostics and performance monitoring, and test-and-learn policy simulations. These use cases allow agencies to build institutional muscle, evaluate governance mechanisms, and learn where AI adds value — without overcommitting or over-automating.

Throughout this process, strong data governance is essential. Inaccurate, incomplete, or poorly labeled data will yield flawed outputs, amplifying errors rather than insight. “Garbage in, garbage out” is a central risk. Clear mandates, constraints, monitoring, and escalation procedures developed by cross-functional teams spanning policy, legal, program, and engineering are what allow experimentation to remain safe, compliant, and aligned with public goals.

AI can do powerful and genuinely useful things for government — but not automatically, and not all at once. The way forward is not sweeping autonomy, but careful institutional reform paired with pragmatic, well-governed experimentation that builds trust, capability, and impact over time.

Summary

AI offers an opportunity to transform government, but its impact depends less on the technology itself and more on how institutions use it. Generative and agentic AI can accelerate analysis and automate complex workflows, yet without structural reforms, clear objectives, human oversight, and guardrails, these tools risk amplifying inefficiency rather than solving it.

The most effective approach is thoughtful, pragmatic experimentation: starting with well-scoped, low-risk pilots while continuously monitoring performance, refining governance, and ensuring alignment with public goals. Leaders should empower teams that can define problems, safely run pilots, and leverage data, tools, and governance to measure, iterate, and scale. Pilot opportunities should involve tractable, visible, high-value workflows with manageable risk and strong data, where improvements can be measured and scaled to inform future AI adoption. Example areas include data integration, workflow coordination, and customer service.

Ultimately, AI’s value to government emerges not from the tools themselves but from redesigning processes, reducing structural bottlenecks, and improving outcomes for both government and the public. Governments that combine technology with deliberate institutional reform and iterative learning will capture the transformative potential of AI while minimizing the risks of misguided modernization.

Thank you for feedback on this article: Alexander Macgillivray, Nicole Wong, Anil Dewan.

The post AI in government: From tools to transformation first appeared on Niskanen Center.

The post AI in government: From tools to transformation appeared first on Niskanen Center.