Today's links

Socialist excellence in New York City (permalink)

In her magnificent 2023 book Doppelganger, Naomi Klein describes the "mirror world" of right wing causes that are weird, conspiratorial versions of the actual things that leftists care about:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/09/05/not-that-naomi/#if-the-naomi-be-klein-youre-doing-just-fine

For example, Trump rode to power on the back of Qanon, a movement driven by conspiratorial theories of a cabal of rich and powerful people who were kidnapping, trafficking and abusing children. Qanon followers were driven to the most unhinged acts by these theories, shooting up restaurants and demanding to be let into nonexistent basements:

https://www.newsweek.com/pizzagate-gunman-killed-north-carolina-qanon-2012850

And while Qanon theories about children being disguised as reasonably priced armoires are facially absurd, the right's obsession with imaginary children is a long-established phenomenon:

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-53416247

Think of the conservative movement's all-consuming obsession with the imaginary lives of children that aborted fetuses might have someday become, and its depraved indifference to the hunger and poverty of actual children in America:

https://unitedwaynca.org/blog/child-poverty-in-america/

Trump's most ardent followers reorganized their lives around the imagined plight of imaginary children, while making excuses for Trump's first-term "Kids in Cages" policy:

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-us-canada-44518942

Obviously, this has only gotten worse in Trump's second term. The same people whose entire political identity is nominally about defending "unborn children" are totally indifferent to the actual born children that DOGE left to die by the thousands:

https://hsph.harvard.edu/news/usaid-shutdown-has-led-to-hundreds-of-thousands-of-deaths/

They cheered Israel's slaughter and starvation of children during the siege of Gaza and they are cheering it on still today:

https://www.savethechildren.net/news/gaza-20000-children-killed-23-months-war-more-one-child-killed-every-hour

As for pedophile traffickers, the same Qanon conspiracy theorists who cooked their brains with fantasies about Trump smiting the elite pedophiles are now making excuses for Trump's central role in history's most prolific child rape scandal:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Relationship_of_Donald_Trump_and_Jeffrey_Epstein

This is the mirror-world as Klein described it: a real problem (elite impunity for child abuse; the sadistic targeting of children in war crimes; the impact of poverty on children) filtered through a fever-swamp of conspiratorial nonsense. It's world that would do anything to save imaginary children while condemning living, real children to grinding poverty, sexual torture, starvation and murder.

Once you know about Klein's mirror-world, you see it everywhere – from conservative panics about the power of Big Tech platforms (that turn out to be panics about what Big Tech does with that power, not about the power of tech itself):

https://pluralistic.net/2026/02/13/khanservatives/#kid-rock-eats-shit

To conservative panics about health – that turn out to be a demand to dismantle America's weak public health system and America's weak regulation of the supplements industry:

https://www.conspirituality.net/episodes/brief-maha-is-a-supplements-grift

But lately, I've been thinking that maybe the mirror shines in both directions: that in addition to the warped reflection of the right's mirror world, there is a left mirror world where we can find descrambled, clarified versions of the right's twisted obsessions.

I've been thinking about this since I read a Corey Robin blog post about Mamdani's campaign rhetoric, in which Mamdani railed against "mediocrity" and promised "excellence":

https://coreyrobin.com/2025/11/15/excellence-over-mediocrity-from-mamdani-to-marx-to-food/

Robin pointed out that while this framing might strike some leftists as oddly right-coded, it has a lineal descent from Marx, who advocated for industrialization and mass production because the alternative would be "universal mediocrity.”

Robin went on to discuss a largely lost thread of "socialist perfectionism" ("John Ruskin and William Morris to Bloomsbury Bolsheviks like Virginia Woolf and John Maynard Keynes") who advocated for the public provision of excellence.

He identifies Marx's own mirror world analysis, pointing out that Marx identified a fundamental difference between capitalist and socialist theories of the division of labor. While capitalists saw the division of labor as a way to increase quantity, socialists were excited by the prospect of increasing quality.

(There's a centaur/reverse centaur comparison lurking in there, too. If you're a centaur radiologist, who gets an AI tool that flags some diagnoses you may have missed, then you're improving the rate of tumor identification. If you're a reverse centaur radiologist who sees 90% of your colleagues fired and replaced with a chatbot whose work you are expected to sign off on at a rate that precludes even cursory inspection, you're increasing X-ray throughput at the expense of accuracy):

https://pluralistic.net/2025/12/05/pop-that-bubble/#u-washington

(In other words: the reverse centaur is the mirror world version of a centaur.)

After the mayoral election, Mamdani doubled down on his pursuit of high-quality public services. In his inaugural speech, Mamdani promised a government "where excellence is no longer the exception":

https://www.nytimes.com/2026/01/01/nyregion/mamdani-inauguration-speech-transcript.html

Robin was also developing his appreciation for Mamadani's vision of public excellence. In the New York Review of Books, Robin made the case that it was a mistake for Democrats to have ceded the language of efficiency and quality to Republicans:

https://www.nybooks.com/online/2025/12/31/democratic-excellence-zohran-mamdani/

Where Democrats do talk about efficiency, they talk about it in Republican terms: "We'll run the government like a business." Mamdani, by contrast, talks about running the government like a government – a good government, a government committed to excellence.

Writing in Jacobin, Conor Lynch takes a trip into the good side of the mirror world, unpacking the idea of socialist excellence in Mamdani's governance promises:

https://jacobin.com/2026/02/zohran-mamdani-efficiency-nyc-budget/

During the Mamdani campaign, "efficiency" was just one plank of the platform. But once Mamdani took office, he learned that his predecessor, the lavishly corrupt Eric Adams, had lied about the city's finances, leaving a $12b hole in the budget:

https://www.nyc.gov/mayors-office/news/2026/01/mayor-mamdani-details–adams-budget-crisis-

Mamdani came to power in New York on an ambitious platform of public service delivery, and not just because this is the right thing to do, but because investment in a city's people and built environment pays off handsomely.

Maintenance is always cheaper than repair, and one of the main differences between a business and a government is that a business's shareholders can starve maintenance budgets, cash out, and leave the collapsing firm behind them, while governments must think about the long term consequences of short-term thinking (the fact that so many Democratic governments have failed to do this is a consequence of Democrats adopting Republicans' framing that a good government is "run like a business").

The best time to invest in New York City was 20 years ago. The second best time in now. For Mamdani to make those investments and correct the failures of his predecessors, he needs to find some money.

Mamdani's proposal for finding this money sounds pretty conservative: he's going to cut waste in government. He's ordered each city agency to appoint a "Chief Savings Officer" who will "review performance, eliminate waste and streamline service delivery." These CSOs are supposed to find a 1.5% across-the-board savings this year and 2.5% next year:

https://www.nyc.gov/mayors-office/news/2026/01/mayor-mamdani-signs-executive-order-to-require-chief-savings-off

Does this sound like DOGE to you? It kind of does to me, but – crucially – this is mirror-world DOGE. DOGE's project was to make cuts to government in order to make government "run like a business." Specifically, DOGE wanted to transform the government into the kind of business that makes cuts to juice the quarterly numbers at the expense of long-term health:

https://www.forbes.com/sites/suzannerowankelleher/2024/10/24/southwest-airlines-bends-to-activist-investor-restructures-board/

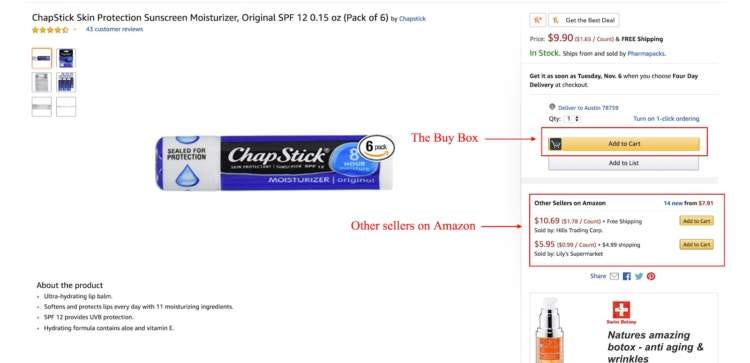

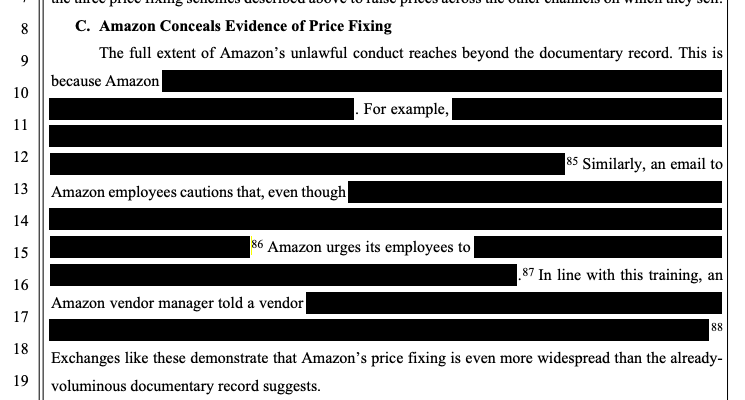

But Mamdani's mirror-world DOGE is looking to find efficiencies by cutting things like sweetheart deals with private contractors and consultants, who cost the city billions. It's these private sector delegates of the state that are the source of government waste and bloat.

The literature is clear on this: when governments eliminate their own capacity to serve the people and hire corporations to do it on their behalf, the corporations charge more and deliver less:

https://calmatters.org/commentary/2019/02/public-private-partnerships-are-an-industry-gimmick-that-dont-serve-public-well/

As Lynch writes, DOGE's purpose was to dismantle as much of the government as possible and shift its duties to Beltway Bandits who could milk Uncle Sucker for every dime. Mamdani's ambition, meanwhile, is to "restore faith in government [and] demonstrate that the public sector can match or even surpass the private sector in excellence."

As Mamdani said in his inauguration speech, "For too long, we have turned to the private sector for greatness, while accepting mediocrity from those who serve the public."

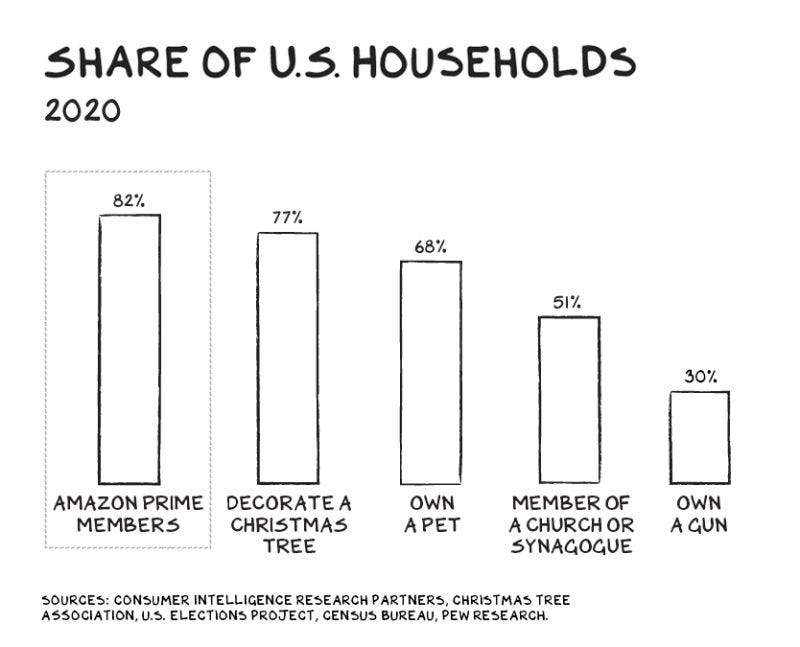

Turning governments into businesses has been an unmitigated failure. After decades of outsourcing, the government hasn't managed to shrink its payroll, but government workers are today primarily employed in wheedling private contractors to fulfill their promises, even as public spending has quintupled:

https://www.brookings.edu/articles/is-government-too-big-reflections-on-the-size-and-composition-of-todays-federal-government/

Instead of having a government employee do a government job, that govvie oversees a private contractor who costs twice as much…and sucks at their job:

https://www.pogo.org/reports/bad-business-billions-of-taxpayer-dollars-wasted-on-hiring-contractors

There's a wonderful illustration of this principle at work in Edward Snowden's 2019 memoir Permanent Record:

https://memex.craphound.com/2019/09/24/permanent-record-edward-snowden-and-the-making-of-a-whistleblower/

After Snowden broke both his legs during special forces training and washed out, he went to work for the NSA. After a couple years, his boss told him that Congress capped the spy agencies' headcount but not their budgets, so he was going to have to quit his job at the NSA and go to work for one of the NSA's many contractors, because the NSA could hire as many contractors as it wanted.

So Snowden is sent to a recruiter who asks him how much he's making as a government spy. Snowden quotes a modest 5-figure sum. The recruiter is aghast and tells Snowden that he gets paid a percentage of whatever Snowden ends up making as a government contractor, and promptly triples Snowden's government salary. Why not? The spy agencies have unlimited budgets, and will pay whatever the private company that Snowden nominally works for bills them at. Everybody wins!

Ladies and gentlemen, the efficiency of government outsourcing. Run the government like a business!

As bad as this is when the government hires outside contractors to do things, it's even worse when they hire outside contractors to consult on things. Under Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, the Canadian government spent a fortune on consultants, especially at the start of the pandemic:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/01/31/mckinsey-and-canada/#comment-dit-beltway-bandits-en-canadien

The main beneficiary of these contracts was McKinsey, who were given a blank cheque and no oversight – they were even exempted from rules requiring them to disclose conflicts of interest.

Trudeau raised Canadian government spending by 40%, to $11.8 billion, creating a "shadow civil service" that cost vastly more than the actual civil service – the government spent $1.85b on internal IT expertise, and $2.3b on outside contractors.

These contractors produced some of the worst IT boondoggles in government history, including the bungled "ArriveCAN" contact tracing program. The two-person shop that won the contract outsourced it to KPMG and raked off a 15-30% commission.

Before Trudeau, Stephen Harper paid IBM to build Phoenix – a payroll system that completely failed and was, amazingly, far worse than ArriveCAN. IBM got $309m to build Phoenix, and then Canada spent another $506m to fix it and compensate the people whose lives it ruined.

Wherever you find these contractors, you find stupendous waste and fraud. I remember in the early 2000s, when Dan "City of Sound" Hill was working at the BBC and wanted to try an experiment to distribute MP3s of a radio programme.

The BBC – an organization with a long history of technical excellence – had given the exclusive contract for web delivery to Siemens, who wanted £10,000 to set up a web-server for the experiment. Dan rented a server from an online provider and put it all on his personal card, serving tens of thousands of MP3s for less than £10. It turns out that letting your technical personnel do your technology development costs 1/1000th of what it costs to have contractors do it.

Running your public institution "like a business" is incredibly inefficient. Back when Musk and Ramaswamy announced their plan to cut $2t from the US federal budget, David Dayen published a plan to realize nearly that much savings just by attacking waste arising from running the government "like a business":

https://pluralistic.net/2025/01/27/beltway-bandits/#henhouse-foxes

The US government's own estimate of the losses due to contractor fraud comes out to $274b/year – roughly the size of the entire civil service payroll (the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, which Musk sadistically destroyed, accounts for 0.012% of federal spending).

Medicare "upcoding" – a form of fraud committed by companies like United Healthcare, the largest Medicare Advantage provider in the country – costs the public $83b/year:

https://www.medpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Mar24_ExecutiveSummary_MedPAC_Report_To_Congress_SEC.pdf

Congress has banned Medicare and Medicaid from bargaining for pharma prices, which is why the US government pays 178% more than other governments, for the same drugs, which are often developed at public expense:

https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/comparing-prescription-drugs

The Pentagon is a cesspit of waste. It's not just firing spies and rehiring them as contractors at a 300% markup – that's just for starters. The Pentagon receives $840b/year and has failed its last three audits:

https://thehill.com/policy/defense/4992913-pentagon-fails-7th-audit-in-a-row-but-says-progress-made/

The conservative version of "efficiency" cashes out to "efficient at extracting value from public institutions, workers and customers." Mamdani's (good) mirror world "efficiency" means providing great public service through investing in public excellence.

New York City is overdue for this kind of overhaul. Everywhere you look in the city, you find high price consultants making out like bandits and starving the city of the funds it needs to deliver. The Second Avenue subway spent more on consultants than it spent on digging tunnels:

https://gothamist.com/news/mta-plans-to-hire-186m-consultant-to-oversee-second-avenue-subway-construction

Mamdani has pledged to audit the Department of Education's 25 largest contracts (the DOE spends $10b/year on outside contractors). He's rolling out "fiscal training and certification" for any government employee involved in procurement.

Mamdani isn't pretending he can bridge the gap that Adams left in the city's finances through efficiency alone: to make up the difference, he is going to tax NYC's millionaires, and ask the state to "rebalance" its relationship with NYC's taxpayers (NYC contributes 54.4% of the state budget, but only gets 40.5% in return).

As Lynch writes, NYC was the birthplace of austerity-driven outsourcing, following from the city's bankruptcy in 1975. 50 years later, Mamdani is bringing that age to a close.

Mamdani knows what the stakes are, too. He called efficiency "the most paramount left-wing concern, because it is either the fulfillment or the betrayal of that which motivates so much of our politics":

https://www.derekthompson.org/p/what-speaks-to-me-about-abundance

Mamdani is reviving the tradition of "sewer socialism," a governing philosophy based on "bringing people into your politics by improving their lives in obvious ways":

https://jacobin.com/2025/12/digital-sewer-socialism-public-ownership

Sewer socialism, public excellence, real efficiency: these are the (good) mirror world versions of the right's obsession with "government efficiency." On the conservative side of the mirror, "efficiency" is an excuse for hamstringing government employees and turning their budgets over to lazy, crooked contractors. On the left's side of the mirror, "efficiency" is building capacity in democratically accountable institutions that care about helping every person, and who deliver tomorrow's excellence by making long-term investments today.

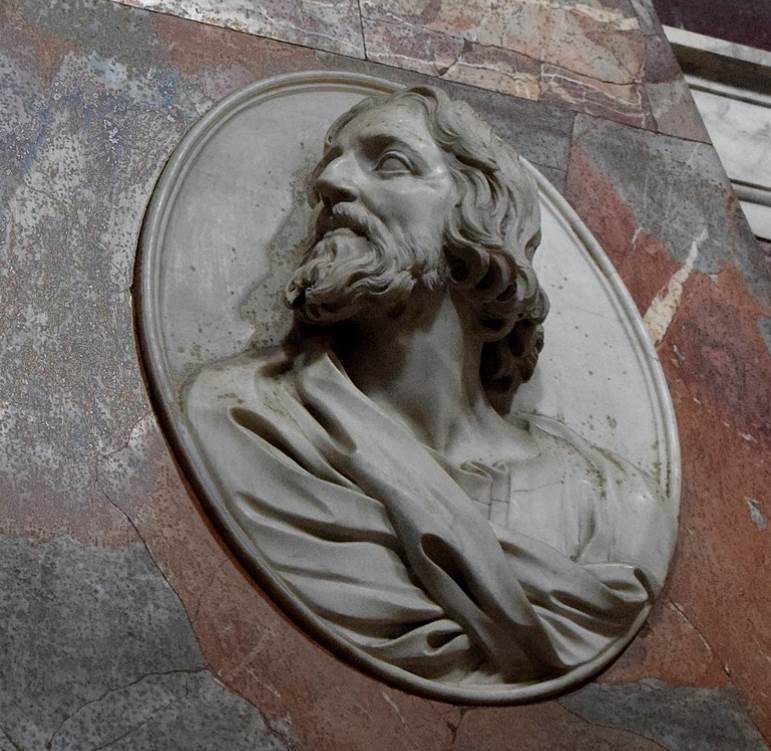

(Image: DAVID ILIFF, CC BY-SA 3.0, modified)

Hey look at this (permalink)

Object permanence (permalink)

#20yrago UK anti-piracy officer assures Firefox she’ll catch the pirates who copy it https://web.archive.org/web/20060511105535/http://business.timesonline.co.uk/article/0,,9075-2051196,00.html

#20yrsago Diane Duane vows to finish trilogy as a reader-supported web-book https://web.archive.org/web/20060630094910/http://outofambit.blogspot.com/2006_02_01_outofambit_archive.html#114069083471800451

#15yrago Order of Odd-Fish, a funny, mannered, hilariously weird epic romp https://memex.craphound.com/2011/02/23/order-of-odd-fish-a-funny-mannered-hilariously-weird-epic-romp/

#15yrsago HOWTO make a batpole flip-top bust switch https://web.archive.org/web/20110218013400/https://www.thenewhobbyist.com/2011/02/wireless-light-switch-or-bust/

#15yrsago Travel guide for American invalids, 1887 https://web.archive.org/web/20110225235315/http://www.butifandthat.com/guide-for-invalids/

#15yrsago Archive.org and 150 libraries create 80,000 lendable ebook library https://archive.org/post/349420/in-library-ebook-lending-program-launched

#15yrsago Scott Walker tricked into spilling his guts to fake Koch brother https://web.archive.org/web/20110226135536/https://www.salon.com/news/the_labor_movement/index.html?story=/politics/war_room/2011/02/23/koch_walker_call

#10yrsago Bill Gates: Microsoft would backdoor its products in a heartbeat https://web.archive.org/web/20160223175618/https://recode.net/2016/02/22/bill-gates-is-backing-the-fbi-in-its-case-against-apple/

#10yrsago Wikileaks: NSA spied on UN Secretary General and world leaders over climate and trade https://wikileaks.org/nsa-201602/

#10yrsago Donald Trump They Live mask https://web.archive.org/web/20160224101815/http://www.trickortreatstudios.com/they-live-alien-donald-trump-limited-edition-halloween-mask.html

#10yrsago Unicorn vs. Goblins: the third amazing, hilarious Phoebe and her Unicorn collection! https://memex.craphound.com/2016/02/23/unicorn-vs-goblins-the-third-amazing-hilarious-phoebe-and-her-unicorn-collection/

#5yrsago German covid coinages https://pluralistic.net/2021/02/23/acceptable-losses/#Zeitgeist

#5yrsago A voyage to the moon of 1776 https://pluralistic.net/2021/02/23/acceptable-losses/#Filippo-Morghen

#5yrsago Malcolm X's true killers https://pluralistic.net/2021/02/23/acceptable-losses/#deathbeds-r-us

#5yrsago Private equity's nursing home killing spree https://pluralistic.net/2021/02/23/acceptable-losses/#disposable-olds

Upcoming appearances (permalink)

Recent appearances (permalink)

- "Canny Valley": A limited edition collection of the collages I create for Pluralistic, self-published, September 2025 https://pluralistic.net/2025/09/04/illustrious/#chairman-bruce

-

"Enshittification: Why Everything Suddenly Got Worse and What to Do About It," Farrar, Straus, Giroux, October 7 2025

https://us.macmillan.com/books/9780374619329/enshittification/

-

"Picks and Shovels": a sequel to "Red Team Blues," about the heroic era of the PC, Tor Books (US), Head of Zeus (UK), February 2025 (https://us.macmillan.com/books/9781250865908/picksandshovels).

-

"The Bezzle": a sequel to "Red Team Blues," about prison-tech and other grifts, Tor Books (US), Head of Zeus (UK), February 2024 (thebezzle.org).

-

"The Lost Cause:" a solarpunk novel of hope in the climate emergency, Tor Books (US), Head of Zeus (UK), November 2023 (http://lost-cause.org).

-

"The Internet Con": A nonfiction book about interoperability and Big Tech (Verso) September 2023 (http://seizethemeansofcomputation.org). Signed copies at Book Soup (https://www.booksoup.com/book/9781804291245).

-

"Red Team Blues": "A grabby, compulsive thriller that will leave you knowing more about how the world works than you did before." Tor Books http://redteamblues.com.

-

"Chokepoint Capitalism: How to Beat Big Tech, Tame Big Content, and Get Artists Paid, with Rebecca Giblin", on how to unrig the markets for creative labor, Beacon Press/Scribe 2022 https://chokepointcapitalism.com

- "The Reverse-Centaur's Guide to AI," a short book about being a better AI critic, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, June 2026

-

"Enshittification, Why Everything Suddenly Got Worse and What to Do About It" (the graphic novel), Firstsecond, 2026

-

"The Post-American Internet," a geopolitical sequel of sorts to Enshittification, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2027

-

"Unauthorized Bread": a middle-grades graphic novel adapted from my novella about refugees, toasters and DRM, FirstSecond, 2027

-

"The Memex Method," Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 2027

Today's top sources:

Currently writing: "The Post-American Internet," a sequel to "Enshittification," about the better world the rest of us get to have now that Trump has torched America ( words today, total)

- "The Reverse Centaur's Guide to AI," a short book for Farrar, Straus and Giroux about being an effective AI critic. LEGAL REVIEW AND COPYEDIT COMPLETE.

-

"The Post-American Internet," a short book about internet policy in the age of Trumpism. PLANNING.

-

A Little Brother short story about DIY insulin PLANNING

This work – excluding any serialized fiction – is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license. That means you can use it any way you like, including commercially, provided that you attribute it to me, Cory Doctorow, and include a link to pluralistic.net.

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Quotations and images are not included in this license; they are included either under a limitation or exception to copyright, or on the basis of a separate license. Please exercise caution.

How to get Pluralistic:

Blog (no ads, tracking, or data-collection):

Pluralistic.net

Newsletter (no ads, tracking, or data-collection):

https://pluralistic.net/plura-list

Mastodon (no ads, tracking, or data-collection):

https://mamot.fr/@pluralistic

Medium (no ads, paywalled):

https://doctorow.medium.com/

Twitter (mass-scale, unrestricted, third-party surveillance and advertising):

https://twitter.com/doctorow

Tumblr (mass-scale, unrestricted, third-party surveillance and advertising):

https://mostlysignssomeportents.tumblr.com/tagged/pluralistic

"When life gives you SARS, you make sarsaparilla" -Joey "Accordion Guy" DeVilla

READ CAREFULLY: By reading this, you agree, on behalf of your employer, to release me from all obligations and waivers arising from any and all NON-NEGOTIATED agreements, licenses, terms-of-service, shrinkwrap, clickwrap, browsewrap, confidentiality, non-disclosure, non-compete and acceptable use policies ("BOGUS AGREEMENTS") that I have entered into with your employer, its partners, licensors, agents and assigns, in perpetuity, without prejudice to my ongoing rights and privileges. You further represent that you have the authority to release me from any BOGUS AGREEMENTS on behalf of your employer.

ISSN: 3066-764X