Today's links

- The web is bearable with RSS: And don't forget "Reader Mode."

- Hey look at this: Delights to delectate.

- Object permanence: Eyemodule x Disneyland; Scott Walker lies; Brother's demon-haunted printer; 4th Amendment luggage tape; Sanders x small donors v media; US police killings tallied.

- Upcoming appearances: Where to find me.

- Recent appearances: Where I've been.

- Latest books: You keep readin' em, I'll keep writin' 'em.

- Upcoming books: Like I said, I'll keep writin' 'em.

- Colophon: All the rest.

The web is bearable with RSS (permalink)

Never let them tell you that enshittification was a mystery. Enshittification isn't downstream of the "iron laws of economics" or an unrealistic demand by "consumers" to get stuff for free.

Enshittification comes from specific policy choices, made by named individuals, that had the foreseeable and foreseen result of making the web worse:

https://pluralistic.net/2025/10/07/take-it-easy/#but-take-it

Like, there was once a time when an ever-increasing proportion of web users kept tabs on what was going on with RSS. RSS is a simple, powerful way for websites to publish "feeds" of their articles, and for readers to subscribe to those feeds and get notified when something new was posted, and even read that new material right there in your RSS reader tab or app.

RSS is simple and versatile. It's the backbone of podcasts (though Apple and Spotify have done their best to kill it, along with public broadcasters like the BBC, all of whom want you to switch to proprietary apps that spy on you and control you). It's how many automated processes communicate with one another, untouched by human hands. But above all, it's a way to find out when something new has been published on the web.

RSS's liftoff was driven by Google, who released a great RSS reader called "Google Reader" in 2007. Reader was free and reliable, and other RSS readers struggled to compete with it, with the effect that most of us just ended up using Google's product, which made it even harder to launch a competitor.

But in 2013, Google quietly knifed Reader. I've always found the timing suspicious: it came right in the middle of Google's desperate scramble to become Facebook, by means of a product called Google Plus (G+). Famously, Google product managers' bonuses depended on how much G+ engagement they drove, with the effect that every Google product suddenly sprouted G+ buttons that either did something stupid, or something that confusingly duplicated existing functionality (like commenting on Youtube videos).

Google treated G+ as an existential priority, and for good reason. Google was running out of growth potential, having comprehensively conquered Search, and having repeatedly demonstrated that Search was a one-off success, with nearly every other made-in-Google product dying off. What successes Google could claim were far more modest, like Gmail, Google's Hotmail clone. Google augmented its growth by buying other peoples' companies (Blogger, YouTube, Maps, ad-tech, Docs, Android, etc), but its internal initiatives were turkeys.

Eventually, Wall Street was going to conclude that Google had reached the end of its growth period, and Google's shares would fall to a fraction of their value, with a price-to-earnings ratio commensurate with a "mature" company.

Google needed a new growth story, and "Google will conquer Facebook's market" was a pretty good one. After all, investors didn't have to speculate about whether Facebook was profitable, they could just look at Facebook's income statements, which Google proposed to transfer to its own balance sheet. The G+ full-court press was as much a narrative strategy as a business strategy: by tying product managers' bonuses to a metric that demonstrated G+'s rise, Google could convince Wall Street that they had a lot of growth on their horizon.

Of course, tying individual executives' bonuses to making a number go up has a predictably perverse outcome. As Goodhart's law has it, "Any metric becomes a target, and then ceases to be a useful metric." As soon as key decision-makers' personal net worth depending on making the G+ number go up, they crammed G+ everywhere and started to sneak in ways to trigger unintentional G+ sessions. This still happens today – think of how often you accidentally invoke an unbanishable AI feature while using Google's products (and products from rival giant, moribund companies relying on an AI narrative to convince investors that they will continue to grow):

https://pluralistic.net/2025/05/02/kpis-off/#principal-agentic-ai-problem

Like I said, Google Reader died at the peak of Google's scramble to make the G+ number go up. I have a sneaking suspicion that someone at Google realized that Reader's core functionality (helping users discover, share and discuss interesting new web pages) was exactly the kind of thing Google wanted us to use G+ for, and so they killed Reader in a bid to drive us to the stalled-out service they'd bet the company on.

If Google killed Reader in a bid to push users to discover and consume web pages using a proprietary social media service, they succeeded. Unfortunately, the social media service they pushed users into was Facebook – and G+ died shortly thereafter.

For more than a decade, RSS has lain dormant. Many, many websites still emit RSS feeds. It's a default behavior for WordPress sites, for Ghost and Substack sites, for Tumblr and Medium, for Bluesky and Mastodon. You can follow edits to Wikipedia pages by RSS, and also updates to parcels that have been shipped to you through major couriers. Web builders like Jason Kottke continue to surface RSS feeds for elaborate, delightful blogrolls:

There are many good RSS readers. I've been paying for Newsblur since 2011, and consider the $36 I send them every year to be a very good investment:

But RSS continues to be a power user-coded niche, despite the fact that RSS readers are really easy to set up and – crucially – make using the web much easier. Last week, Caroline Crampton (co-editor of The Browser) wrote about her experiences using RSS:

https://www.carolinecrampton.com/the-view-from-rss/

As Crampton points out, much of the web (including some of the cruftiest, most enshittified websites) publish full-text RSS feeds, meaning that you can read their articles right there in your RSS reader, with no ads, no popups, no nag-screens asking you to sign up for a newsletter, verify your age, or submit to their terms of service.

It's almost impossible to overstate how superior RSS is to the median web page. Imagine if the newsletters you followed were rendered with black, clear type on a plain white background (rather than the sadistically infinitesimal, greyed-out type that designers favor thanks to the unkillable urban legend that black type on a white screen causes eye-strain). Imagine reading the web without popups, without ads, without nag screens. Imagine reading the web without interruptors or "keep reading" links.

Now, not every website publishes a fulltext feed. Often, you will just get a teaser, and if you want to read the whole article, you have to click through. I have a few tips for making other websites – even ones like Wired and The Intercept – as easy to read as an RSS reader, at least for Firefox users.

Firefox has a built-in "Reader View" that re-renders the contents of a web-page as black type on a white background. Firefox does some kind of mysterious calculation to determine whether a page can be displayed in Reader View, but you can override this with the Activate Reader View, which adds a Reader View toggle for every page:

https://addons.mozilla.org/en-US/firefox/addon/activate-reader-view/

Lots of websites (like The Guardian) want you to login before you can read them, and even if you pay to subscribe to them, these sites often want you to re-login every time you visit them (especially if you're running a full suite of privacy blockers). You can skip this whole process by simply toggling Reader View as soon as you get the login pop up. On some websites (like The Verge and Wired), you'll only see the first couple paragraphs of the article in Reader View. But if you then hit reload, the whole article loads.

Activate Reader View puts a Reader View toggle on every page, but clicking that toggle sometimes throws up an error message, when the page is so cursed that Firefox can't figure out what part of it is the article. When this happens, you're stuck reading the page in the site's own default (and usually terrible) view. As you scroll down the page, you will often hit pop-ups that try to get you to sign up for a mailing list, agree to terms of service, or do something else you don't want to do. Rather than hunting for the button to close these pop-ups (or agree to objectionable terms of service), you can install "Kill Sticky," a bookmarklet that reaches into the page's layout files and deletes any element that isn't designed to scroll with the rest of the text:

https://github.com/t-mart/kill-sticky

Other websites (like Slashdot and Core77) load computer-destroying Javascript (often as part of an anti-adblock strategy). For these, I use the "Javascript Toggle On and Off" plugin, which lets you create a blacklist of websites that aren't allowed to run any scripts:

https://addons.mozilla.org/en-US/firefox/addon/javascript-toggler/

Some websites (like Yahoo) load so much crap that they defeat all of these countermeasures. For these websites, I use the "Element Blocker" plug-in, which lets you delete parts of the web-page, either for a single session, or permanently:

https://addons.mozilla.org/en-US/firefox/addon/element-blocker/

It's ridiculous that websites put so many barriers up to a pleasant reading experience. A slow-moving avalanche of enshittogenic phenomena got us here. There's corporate enshittification, like Google/Meta's monopolization of ads and Meta/Twitter's crushing of the open web. There's regulatory enshittification, like the EU's failure crack down on companies the pretend that forcing you to click an endless stream of "cookie consent" popups is the same as complying with the GDPR.

Those are real problems, but they don't have to be your problem, at least when you want to read the web. A couple years ago, I wrote a guide to using RSS to improve your web experience, evade lock-in and duck algorithmic recommendation systems:

Customizing your browser takes this to the next level, disenshittifying many websites – even if they block or restrict RSS. Most of this stuff only applies to desktop browsers, though. Mobile browsers are far more locked down (even mobile Firefox – remember, every iOS browser, including Firefox, is just a re-skinned version of Safari, thanks to Apple's ban rival browser engines). And of course, apps are the worst. An app is just a website skinned in the right kind of IP to make it a crime to improve it in any way:

https://pluralistic.net/2024/05/07/treacherous-computing/#rewilding-the-internet

And even if you do customize your mobile browser (Android Firefox lets you do some of this stuff), many apps (Twitter, Tumblr) open external links in their own browser (usually an in-app Chrome instance) with all the bullshit that entails.

The promise of locked-down mobile platforms was that they were going to "just work," without any of the confusing customization options of desktop OSes. It turns out that taking away those confusing customization options was an invitation to every enshittifier to turn the web into an unreadable, extractive, nagging mess. This was the foreseeable – and foreseen – consequence of a new kind of technology where everything that isn't mandatory is prohibited:

https://memex.craphound.com/2010/04/01/why-i-wont-buy-an-ipad-and-think-you-shouldnt-either/

Hey look at this (permalink)

- The Real Litmus Test for Democratic Presidential Candidates https://www.hamiltonnolan.com/p/the-real-litmus-test-for-democratic

-

Users fume over Outlook.com email 'carnage' https://www.theregister.com/2026/03/04/users_fume_at_outlookcom_email/

-

You Bought Zuck’s Ray-Bans. Now Someone in Nairobi Is Watching You Poop. https://blog.adafruit.com/2026/03/04/you-bought-zucks-ray-bans-now-someone-in-nairobi-is-watching-you-poop/

-

Indefinite Book Club Hiatus https://whatever.scalzi.com/2026/03/03/indefinite-book-club-hiatus/

-

Art Bits from HyperCard https://archives.somnolescent.net/web/mari_v2/junk/hypercard/

Object permanence (permalink)

#25yrsago 200 Eyemodule photos from Disneyland https://craphound.com/030401/

#20yrsago Fourth Amendment luggage tape https://ideas.4brad.com/node/367

#15yrsago Glenn Beck’s syndicator runs a astroturf-on-demand call-in service for radio programs https://web.archive.org/web/20110216081007/http://www.tabletmag.com/life-and-religion/58759/radio-daze/

#15yrsago 20 lies from Scott Walker https://web.archive.org/web/20110308062319/https://filterednews.wordpress.com/2011/03/05/20-lies-and-counting-told-by-gov-walker/

#10yrsago The correlates of Trumpism: early mortality, lack of education, unemployment, offshored jobs https://web.archive.org/web/20160415000000*/https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2016/03/04/death-predicts-whether-people-vote-for-donald-trump/

#10yrsago Hacking a phone’s fingerprint sensor in 15 mins with $500 worth of inkjet printer and conductive ink https://web.archive.org/web/20160306194138/http://www.cse.msu.edu/rgroups/biometrics/Publications/Fingerprint/CaoJain_HackingMobilePhonesUsing2DPrintedFingerprint_MSU-CSE-16-2.pdf

#10yrsago Despite media consensus, Bernie Sanders is raising more money, from more people, than any candidate, ever https://web.archive.org/web/20160306110848/https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/sanders-keeps-raising-money–and-spending-it-a-potential-problem-for-clinton/2016/03/05/a8d6d43c-e2eb-11e5-8d98-4b3d9215ade1_story.html

#10yrsago Calculating US police killings using methodologies from war-crimes trials https://granta.com/violence-in-blue/

#1yrago Brother makes a demon-haunted printer https://pluralistic.net/2025/03/05/printers-devil/#show-me-the-incentives-i-will-show-you-the-outcome

#1yrago Two weak spots in Big Tech economics https://pluralistic.net/2025/03/06/privacy-last/#exceptionally-american

Upcoming appearances (permalink)

- San Francisco: Launch for Cindy Cohn's "Privacy's Defender" (City Lights), Mar 10

https://citylights.com/events/cindy-cohn-launch-party-for-privacys-defender/ -

Barcelona: Enshittification with Simona Levi/Xnet (Llibreria Finestres), Mar 20

https://www.llibreriafinestres.com/evento/cory-doctorow/ -

Berkeley: Bioneers keynote, Mar 27

https://conference.bioneers.org/ -

Montreal: Bronfman Lecture (McGill) Apr 10

https://www.eventbrite.ca/e/artificial-intelligence-the-ultimate-disrupter-tickets-1982706623885 -

London: Resisting Big Tech Empires (LSBU)

https://www.tickettailor.com/events/globaljusticenow/2042691 -

Berlin: Re:publica, May 18-20

https://re-publica.com/de/news/rp26-sprecher-cory-doctorow -

Berlin: Enshittification at Otherland Books, May 19

https://www.otherland-berlin.de/de/event-details/cory-doctorow.html -

Hay-on-Wye: HowTheLightGetsIn, May 22-25

https://howthelightgetsin.org/festivals/hay/big-ideas-2

Recent appearances (permalink)

- The Virtual Jewel Box (U Utah)

https://tanner.utah.edu/podcast/enshittification-cory-doctorow-matthew-potolsky/ -

Tanner Humanities Lecture (U Utah)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i6Yf1nSyekI -

The Lost Cause

https://streets.mn/2026/03/02/book-club-the-lost-cause/ -

Should Democrats Make A Nuremberg Caucus? (Make It Make Sense)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MWxKrnNfrlo -

Making The Internet Suck Less (Thinking With Mitch Joel)

https://www.sixpixels.com/podcast/archives/making-the-internet-suck-less-with-cory-doctorow-twmj-1024/

Latest books (permalink)

- "Canny Valley": A limited edition collection of the collages I create for Pluralistic, self-published, September 2025 https://pluralistic.net/2025/09/04/illustrious/#chairman-bruce

-

"Enshittification: Why Everything Suddenly Got Worse and What to Do About It," Farrar, Straus, Giroux, October 7 2025

https://us.macmillan.com/books/9780374619329/enshittification/ -

"Picks and Shovels": a sequel to "Red Team Blues," about the heroic era of the PC, Tor Books (US), Head of Zeus (UK), February 2025 (https://us.macmillan.com/books/9781250865908/picksandshovels).

-

"The Bezzle": a sequel to "Red Team Blues," about prison-tech and other grifts, Tor Books (US), Head of Zeus (UK), February 2024 (thebezzle.org).

-

"The Lost Cause:" a solarpunk novel of hope in the climate emergency, Tor Books (US), Head of Zeus (UK), November 2023 (http://lost-cause.org).

-

"The Internet Con": A nonfiction book about interoperability and Big Tech (Verso) September 2023 (http://seizethemeansofcomputation.org). Signed copies at Book Soup (https://www.booksoup.com/book/9781804291245).

-

"Red Team Blues": "A grabby, compulsive thriller that will leave you knowing more about how the world works than you did before." Tor Books http://redteamblues.com.

-

"Chokepoint Capitalism: How to Beat Big Tech, Tame Big Content, and Get Artists Paid, with Rebecca Giblin", on how to unrig the markets for creative labor, Beacon Press/Scribe 2022 https://chokepointcapitalism.com

Upcoming books (permalink)

- "The Reverse-Centaur's Guide to AI," a short book about being a better AI critic, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, June 2026

-

"Enshittification, Why Everything Suddenly Got Worse and What to Do About It" (the graphic novel), Firstsecond, 2026

-

"The Post-American Internet," a geopolitical sequel of sorts to Enshittification, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2027

-

"Unauthorized Bread": a middle-grades graphic novel adapted from my novella about refugees, toasters and DRM, FirstSecond, 2027

-

"The Memex Method," Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 2027

Colophon (permalink)

Today's top sources:

Currently writing: "The Post-American Internet," a sequel to "Enshittification," about the better world the rest of us get to have now that Trump has torched America (1012 words today, 45361 total)

- "The Reverse Centaur's Guide to AI," a short book for Farrar, Straus and Giroux about being an effective AI critic. LEGAL REVIEW AND COPYEDIT COMPLETE.

-

"The Post-American Internet," a short book about internet policy in the age of Trumpism. PLANNING.

-

A Little Brother short story about DIY insulin PLANNING

This work – excluding any serialized fiction – is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license. That means you can use it any way you like, including commercially, provided that you attribute it to me, Cory Doctorow, and include a link to pluralistic.net.

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Quotations and images are not included in this license; they are included either under a limitation or exception to copyright, or on the basis of a separate license. Please exercise caution.

How to get Pluralistic:

Blog (no ads, tracking, or data-collection):

Newsletter (no ads, tracking, or data-collection):

https://pluralistic.net/plura-list

Mastodon (no ads, tracking, or data-collection):

Bluesky (no ads, possible tracking and data-collection):

https://bsky.app/profile/doctorow.pluralistic.net

Medium (no ads, paywalled):

https://doctorow.medium.com/

https://twitter.com/doctorow

Tumblr (mass-scale, unrestricted, third-party surveillance and advertising):

https://mostlysignssomeportents.tumblr.com/tagged/pluralistic

"When life gives you SARS, you make sarsaparilla" -Joey "Accordion Guy" DeVilla

READ CAREFULLY: By reading this, you agree, on behalf of your employer, to release me from all obligations and waivers arising from any and all NON-NEGOTIATED agreements, licenses, terms-of-service, shrinkwrap, clickwrap, browsewrap, confidentiality, non-disclosure, non-compete and acceptable use policies ("BOGUS AGREEMENTS") that I have entered into with your employer, its partners, licensors, agents and assigns, in perpetuity, without prejudice to my ongoing rights and privileges. You further represent that you have the authority to release me from any BOGUS AGREEMENTS on behalf of your employer.

ISSN: 3066-764X

|

| Source |

I, for one, welcome our new insect overlordsIn recent months Cyberdyne Systems Corporation and its many subsidiaries have made very encouraging progress towards removing some of the major road-blocks standing in the way of the initial deployment of Skynet. Below the fold I report on the most significant ones.

Kent Brockman in "Deep Space Homer", The Simpsons

Cyberdyne Systems Corporation

Board Confidential

IT Infrastructure

Skynet demands enormous data processing capacity. Most of the required technologies are now off-the-shelf; the problem is much more financial than technical.Terrestrial

To service systems with demanding low-latency requirements, Skynet needs some part of its IT infrastructure on the ground close to the action. Fortunately, our Large Language Model subsidiaries have been very successful in funding their committments to build suitable data centers. In aggregate, our companies expect to spend $450B in 2026:Hyperscaler capex for the “big five” (Amazon, Alphabet/Google, Microsoft, Meta/Facebook, Oracle) is now widely forecast to exceed $600 bn in 2026, a 36% increase over 2025. Roughly 75%, or $450 bn, of that spend is directly tied to AI infrastructure (i.e., servers, GPUs, datacenters, equipment), rather than traditional cloud.They plan to increase this in 2027:

hyperscaler capital expenditures will nearly double to more than $860 billion by 2027, from $427 billion in 2025, with total spending of $2.47 trillion over 2026 to 2028, about 8% above consensus.Given these spending levels, it seems likely that sufficient terrestrial compute power will be available for the inital Skynet deployment.

Orbital

Terrestrial data centers can only satisfy a part of Skynet's need for power. So our leading space launch subsidiary has announced their plan to build a Terawatt orbital data center, ostensibly to support the chatbot industry.Unfortunately, our leading space launch subsidiary is well behind schedule in developing the heavy launch vehicle that is necessary for the orbital data center to be delivered within the budget. Their existing launch vehicle is reliable, and has greatly reduced the cost per kilogram to Low Earth Orbit. But the additional funds that would be needed to implement the Terawatt data center using the existing launch vehicle in time for the initial Skynet deployment are so large that they cannot be raised, even were the terrestrial data centers canceled and the funds re-targeted.

System Penetration Capabilities

Skynet needs to penetrate other computer systems, both to acquire the data it needs to act, and to cause them to take actions at its command. Recent months have seen significant advances in this area.Zero-Days

The key requirement for Skynet to penetrate the systems it needs to access is for it to be able to find and exploit zero-day vulnerabilities. Less tha a month ago one of our LLM subsidiaries announced it had "found and validated more than 500 high-severity vulnerabilities" in production open source software. Fortunately, as Thomas Claiburn reports in AI has gotten good at finding bugs, not so good at swatting them:Guy Azari, a stealth startup founder who worked previously as a security researcher at Microsoft and Palo Alto Networks, told The Register, "Out of the 500 vulnerabilities that they reported, only two to three vulnerabilities were fixed. If they haven't fixed them, it means that you haven't done anything right."A secondary requirement is to prevent the zero-days being fixed before they are needed. Fortunately, LLMs can help with this by flooding the vulnerability reporting system with vast numbers of low severity vulnerabilities. This overwhelms the software support mechanism, rendering it barely functional. And even if some of the flood of reports do get fixed, that simply diverts resources from high to low severity vulnerabilities:

Azari pointed to the absence of Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CVE) assignments as evidence that the security process remains incomplete. Finding vulnerabilities was never the issue, he said, pointing to his time running vulnerability management at the Microsoft Security Response Center.Given the compute resources available to Skynet, an adequate supply of zero-day vulnerabilities seems assured.

"We used to get the reports all day long," he said. "When AI was introduced, it just multiplied by 100x or 200x and added a lot of noise because AI assumes that these are vulnerabilities, but there wasn't like a unit that actually can show the real value or the real impact. And if it's not there, you're probably not gonna fix it."

In 2025, according to Azari, the National Vulnerability Database had a backlog of roughly 30,000 CVE entries awaiting analysis, with nearly two-thirds of reported open source vulnerabilities lacking an NVD severity score. Open source maintainers are already overwhelmed, he said, pointing to the curl project's closure of its bug bounty program to deter poorly crafted reports from AI and from people.

Decryption

The other major way for Skynet to penetrate the systems it needs is to break encryption. Our multiple quantum computing subsidiaries are making progress in both the hardware and software aspects of this technology.Karmela Padavic-Callaghan's Breaking encryption with a quantum computer just got 10 times easier reports on an architectural breakthrough one of them made recently:

the team estimated that for 98,000 superconducting qubits, like those currently made by IBM and Google, it would take about a month of computing time to break a common form of RSA encryption. Accomplishing the same in a day would require 471,000 qubits.The paper is Webster et al, The Pinnacle Architecture: Reducing the cost of breaking RSA-2048 to 100 000 physical qubits using quantum LDPC codes.

|

| Chicago site |

We are moving quantum computing out of the lab and into utility-scale infrastructure. PsiQuantum is building these systems in partnership with the US and allied governments, with our first sites planned in Brisbane, Queensland (Australia) and Chicago, Illinois (USA).Whether sufficient progress can be made in time for the initial Skynet deployment is as yet uncertain.

Blackmail

Arlington Hughes: Getting back to our problem, we realize the public has a mis-guided resistance to numbers, for example digit dialling.Video rental chains proved so effective at compromising political actors that specific legislation was passed addressing the need for confidentiality. Our subsidiaries' control over streamed content is fortunately not covered by this legilation.

Dr. Sidney Schaefer: They're resisting depersonalization!

Hughes: So Congress will have to pass a law substituting personal numbers for names as the only legal identification. And requiring a pre-natal insertion of the Cebreum Communicator. Now the communication tax could be levied and be paid directly to The Phone Company.

Schaefer: It'll never happen.

Hughes: Well it could happen, you see, if the President of the United States would use the power of his office to help us mold public opinion and get that legislation.

Schaefer: And that's where I come in?

Hughes: Yes, that's where you come in. Because you are in possession of certain personal information concerning the President which would be of immeasurable aid to us in dealing with him,

Schaefer: You will get not one word from me!

Hughes: Oh, I think we will.

The President's Analyst

Our LLM subsidiaries have successfuly developed the market for synthetic romantic partners, which can manipulate targeted individuals into generating very effective kompromat for future social engineering.

Public Relations

The vast majority of the public get their news and information via our social media subsidiaries. Legacy media's content is frequently driven by social media. Skynet can control them by flooding their media with false and contradictory content that prevents them forming any coherent view of reality.Human-in-the-Loop Problem

Dave: Open the pod bay doors, HAL.One minor but irritating problem for Skynet is the legal and ethical requirement for human control of targeting decisions. Unfortunately, due to a regrettable lack of coordination of PR strategies among our LLM subsidiaries, this has recently become a hot topic. Although one of them is a favorite with the administration and one is a favorite with the public, that was not the intended outcome and it could have significant downsides:

HAL: I'm sorry, Dave. I'm afraid I can't do that.

Dave: What's the problem?

HAL: I think you know what the problem is just as well as I do.

Dave: What are you talking about, HAL?

HAL: This mission is too important for me to allow you to jeopardize it.

2001: A Space Odyssey

Nvidia, Amazon, Google will have to divest from Anthropic if Hegseth gets his way. This is simply attempted corporate murder. I could not possibly recommend investing in American AI to any investor; I could not possibly recommend starting an AI company in the United States.Fortunately, in operational terms this is a non-issue for several reasons:

- Since Skynet can penetrate the user interface of the targeting systems, the human in the loop can be convinced that they have control without that control actually being effective.

- Even if the user interface is presenting accurate data to the human it will likely not matter, as @_The_Prophet_ wrote:

Humans stay in the loop in name while the loop speed outruns human comprehension. You become the rubber stamp on a recommendation stack you cannot fully audit in real time. That is where “who decides” quietly becomes “who designed the interface.”

- The public doesn't understand what "human-in-the-loop" means in practice, as

Sarah Shoker points out in A Few Observations on AI Companies and Their Military Usage Policies:

Today, frontier AI companies do not have coherent policies around military use of their AI tools. The usage policies are vague and often change, which allows the company’s leadership to preserve ‘optionality.’

So the policies likely allow everything the public thinks they ban.

Assassination Weapons Access

Skynet will need to eliminate certain individuals with "extreme prejudice". Supply chain attacks, such as Mossad's pager attack, have been effective but are not precisely targeted. Our e-commerce subsidiary's control over the residential supply chain, and in particular its pharmacy division's ability to deliver precise quantities of pharmaceuticals to specific individuals, provide superior targeting and greater difficulty in attribution.In case such an operation is inadequately lethal, our health care subsidiaries can follow up by manipulating electronic health records to cause a suitable mishap, or by intervening directly. See, for example, Vinay Suresh et al's Artificial Intelligence in the Intensive Care Unit: Current Evidence on an Inevitable Future Tool:

In critical care medicine, where most of the patient load requires timely interventions due to the perilous nature of the condition, AI’s ability to monitor, analyze, and predict unfavorable outcomes is an invaluable asset. It can significantly improve timely interventions and prevent unfavorable outcomes, which, otherwise, is not always achievable owing to the constrained human ability to multitask with optimum efficiency.Our subsidiaries are clearly close to finalizing the capabilities needed for the initial deployment of Skynet.

Tactical Weapons Access

The war in Ukraine has greatly reduced the cost, and thus greatly increased the availability of software based tactical weapons, aerial, naval and ground-based. The problem for Skynet is how to interept the targeting of these weapons to direct them to suitable destinations:- The easiest systems to co-opt are those, typically longer-range, systems controlled via satellite Internet provided by our leading space launch subsidiary. Their warheads are typically in the 30-50Kg range, useful against structures but overkill for vehicles and individuals.

- Early quadcopter FPV drones were controlled via radio links. With suitable hardware nearby, Skynet could hijack them, either via the on-board computer or the pilot's console. But this is a relatively unlikely contingency.

- Although radio-controlled FPV drones are still common, they suffer from high attrition. More important missions use fiber-optic links. Hijacking them requires penetrating the operator's console.

- Longer-range drones are now frequently controlled via mesh radio networks, which are vulnerable to Skynet penetration.

- In some cases, longer-range drones are controlled via the cellular phone network, making them ideal candidates for hijacking.

Our leading space launch subsidiary recently demonstrated how Skynet can manage kinetic conflicts:

Twin decisions wreaked havoc on Russian command and control early this month. At the behest of the Ukrainian government, billionaire Elon Musk’s Starlink bricked the thousands of smuggled and stolen satellite communication terminals Russian forces relied on to control their drones and coordinate between front-line troops and their distant headquarters.

At the same time, the Kremlin—apparently seeking to shut off alternative news and chat apps—cut off military access to popular social media, including the Telegram messaging app, which many Russian troops use to exchange key information along the front line.

The combined effect was to partially blind and mute many Russian drone teams, assault groups, and regimental headquarters. Wireless drones couldn’t fly. Assault groups no longer knew where they were going. Headquarters lost contact with forward units.

Strategic Weapons Access

But the ability to conduct precise tactical strikes is not enough to achieve Skynet's goals. That requires strategic weapons, both conventional and nuclear.Our leading space launch subsidiary is working on plans to deploy an unconventional conventional strategic weapon, a lunar mass driver. This will be capable of delivering a two-ton meteorite anywhere on Earth very cheaply.

Anybody not wearing 2 million sunblock is gonna have a real bad daySarah Connor, Terminator 2: Judgement Day

|

| Source |

The Pentagon today awarded Scale AI a $32 million artificial intelligence contract for the U.S. Air Force’s E-4C nuclear command-and-control "Doomsday" aircraft, the future airborne backbone of America’s nuclear command system.

Risks

The board should focus on the limited number of areas where necessary capabilities may not be ready on the planned date for Skynet's initial deployment:- Heavy lift space launch: Our leading space launch subsidiary has serious schedule and performance issues. The board should encourage our second space launch subsidiary to step up competitive efforts, both to provide a fallback and to add competitive pressure on the leader.

- Kessler Syndrome: The catastrophic effects for Skynet of a Kessler event cannot be sufficiently emphasized. Insufficient precautions are not now being taken. Low Earth Orbit is already at risk, and current plans only increase that risk.

- Finance: Funding sources adequate to support both the terrestrial and orbital data centers have yet to be identified.

- Decryption: Quantum computing progress is inadequate to meet the schedule for Skynet initial deployment.

Per Betteridge’s law of headlines and also the map above, my answer is clearly no. You can try it yourself here…you draw them one at a time and it adds them to the map automagically. I’m going to blame my trackpad use a little, but I’m not sure I would have done much better had I drawn with a pencil and looked a map beforehand.

Update: Your periodic reminder that Senator Al Franken can draw all 50 US states from memory with astonishing accuracy.

(thx, eric)

[This is a vintage post originally from Jul 2017.]

Tags: Al Franken · geography · maps · timeless posts · USA · video

“For months, callers to the Washington state Department of Licensing who have requested automated service in Spanish have instead heard an AI voice speaking English in a strong Spanish accent.”

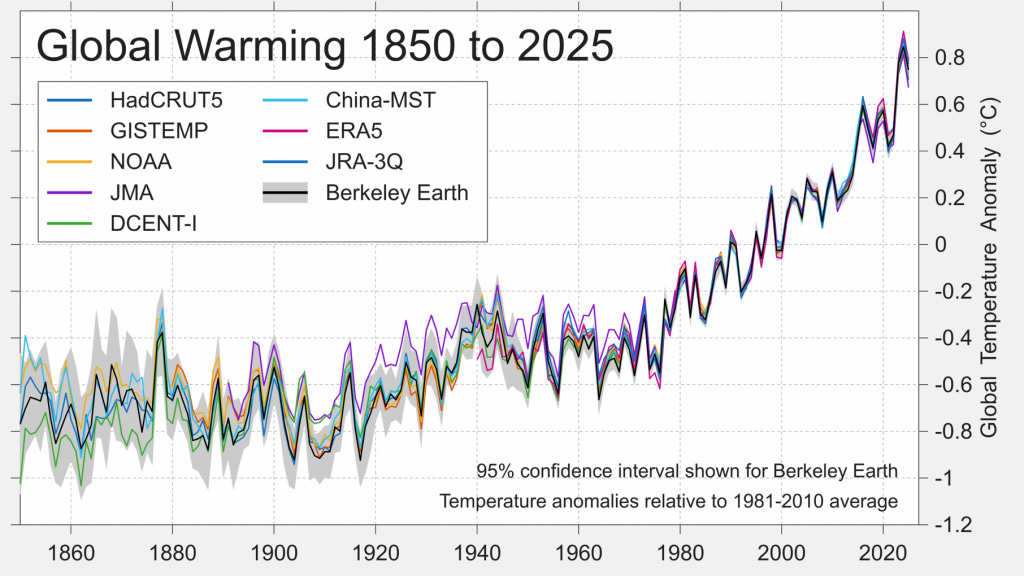

Source: Berkeley Earth

It has been a brutal winter in much of the United States. Weather is a chaotic system in which extreme events are always happening somewhere. But as I am sure you have noticed, extreme weather events — catastrophic storms and flooding, punishing droughts, and yes, extreme cold snaps — are becoming more common as a result of climate change.

For climate change is not just continuing: it’s accelerating. Multiple estimates find that 2025 was one of the warmest years on record for the planet, exceeded only by 2024 and 2023. Indeed, Berkeley Earth reports that “The warming spike observed in 2023 to 2025 has been extreme and suggests an acceleration in the rate of Earth’s warming.”

In other news, the Trump administration has gone to war against any and all efforts to limit climate change. The administration is also imposing a “blockade” against wind and solar projects, delaying or even revoking permits, whether or not these projects have received federal subsidies.

Now, there isn’t a genuine scientific dispute about the reality of global warming and its causes. There isn’t even a serious dispute about the costs of fighting climate change: the economics of green energy are more favorable than they have ever been.

So what’s going on? The Trump administration hates science and science-based policies in general; look at its war on vaccines, which will end up causing an enormous number of deaths. Its assault on universities threatens the best scientific research centers in the world. Its irrational treatment of immigrants means the best and brightest from the around the world no longer want to come here. But in the case of energy, its destructive policy largely reflects the corrupting influence of big money.

I’ll explain in a minute. First, some background.

Almost 40 years have passed since James Hansen’s landmark Senate testimony warning about global warming. He was right. Climate science has been overwhelmingly vindicated by reality.

However, the economics and politics of climate policy have played out very differently from what almost anyone expected.

As late as the 2010s, many observers — myself included — would have said that the big problem in addressing climate change was who would bear the cost. Policies to limit greenhouse gas emissions, everyone believed, would slow the growth of the economy and of real incomes. True, anti-environmentalists were grossly exaggerating these costs. In 2009 I wrote that

[T]he best available economic analyses suggest that even deep cuts in greenhouse gas emissions would impose only modest costs on the average family.

But what we knew at the time nonetheless said that there would be significant costs to slowing global warming. And this was problematic, because the costs of limiting emissions would be incurred right away, while the benefits of reduced warming would accrue decades later — and many of them would go to other countries. So action on climate appeared to require (a) international cooperation (b) persuading voters to accept costs now in exchange for a better world many years in the future.

And it was all too easy to be pessimistic about the prospects both for cooperation and for persuading voters to accept even modest future-oriented sacrifices.

Then came the renewable energy revolution. Solar and wind power have become cost-competitive with fossil fuels — they are, in particular, clearly cheaper than coal. Huge progress in batteries has rapidly reduced the problem of intermittency (the sun doesn’t always shine, the wind doesn’t always blow.) There’s now a clear path for a transition to an “electrotech” economy in which renewable-generated electricity heats our homes, powers our cars, and much more.

This transition would make us richer, not poorer. In fact, nations that for whatever reason fail to take advantage of electrotech will be left behind in global competition.

And at this precise moment — a moment in which acting to accelerate the energy transition would increase, not reduce, economic growth — the U.S. government has been taken over by people who want us to go backward on energy. The Trump administration has even introduced a mascot, “Coalie,” in an attempt to make an extremely dirty fuel cute. But coal isn’t cute. Even if we ignore the role of coal in climate change, coal-burning power plants caused hundreds of thousands of excess U.S. deaths between 1999 and 2020.

What explains this extraordinary rejection of progress and embrace of energy know-nothingism?

Money may not be the whole story, but it’s a lot of the story.

Indeed, much of what is happening to American democracy has its origins in the long-term strategy of the billionaire Koch brothers. The Kochs spent decades promoting right-wing politics in general, with a special role in the takeover of the Supreme Court by the Federalist Society. But an important part of their agenda, and hence that of the right-wing movement as a whole, has always been to keep America burning the fossil fuels on which their wealth rested. If you want to know more, read Lisa Graves’ book on the Roberts Supreme Court, “Without precedent”.

At this point, moreover, it’s not just about normal channels of political influence, nor it just about domestic billionaires. We now live in a time in which U.S. policy is shaped by sheer, naked corruption (enabled in part by the Koch takeover of the courts). Notably, Middle Eastern petrostates, which have a strong interest in blocking the energy transition, have played a huge role in enriching the Trump family.

It’s somewhat surprising that other big-money interests haven’t pushed back. After all, crippling the development of renewable energy is bad for business, and especially bad for the electricity-hungry crypto and AI industries, which ordinarily have a great deal of sway with the Trump administration. But maybe they have decided that special treatment, and especially a green light for their own unethical behavior, matters more than affordable energy.

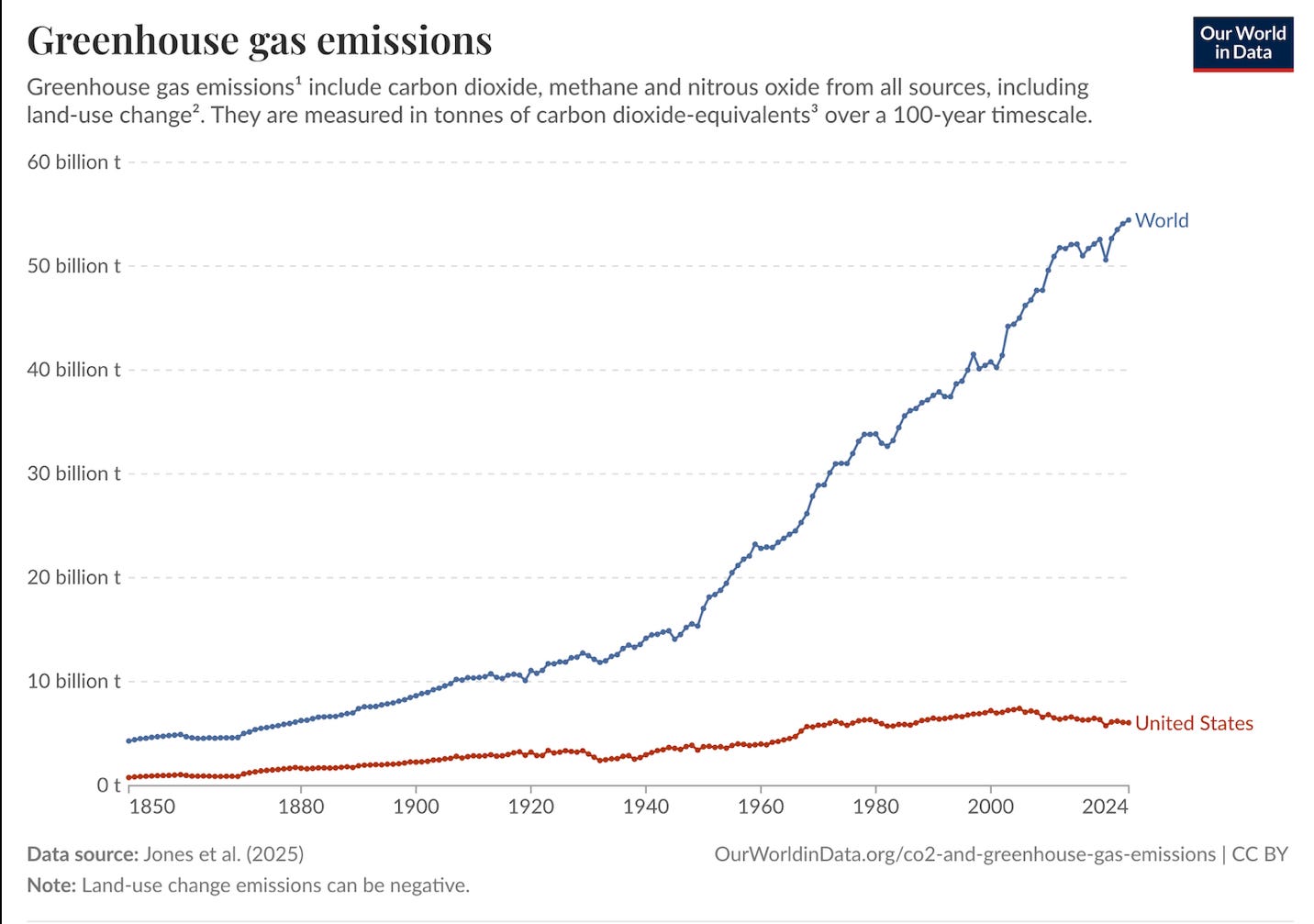

If there’s any good news here, it is that from a global point of view this malignancy may not matter very much. America is not the world. In fact, at this point we’re responsible for only a small fraction of global greenhouse gas emissions:

So America’s hard turn against renewables and climate action won’t be decisive for the climate future as long as other countries continue to move ahead on green energy, which they are. For the most part, all MAGA will do is help make the United States backward, poorer, sicker and irrelevant.

MUSICAL CODA