“For months, callers to the Washington state Department of Licensing who have requested automated service in Spanish have instead heard an AI voice speaking English in a strong Spanish accent.”

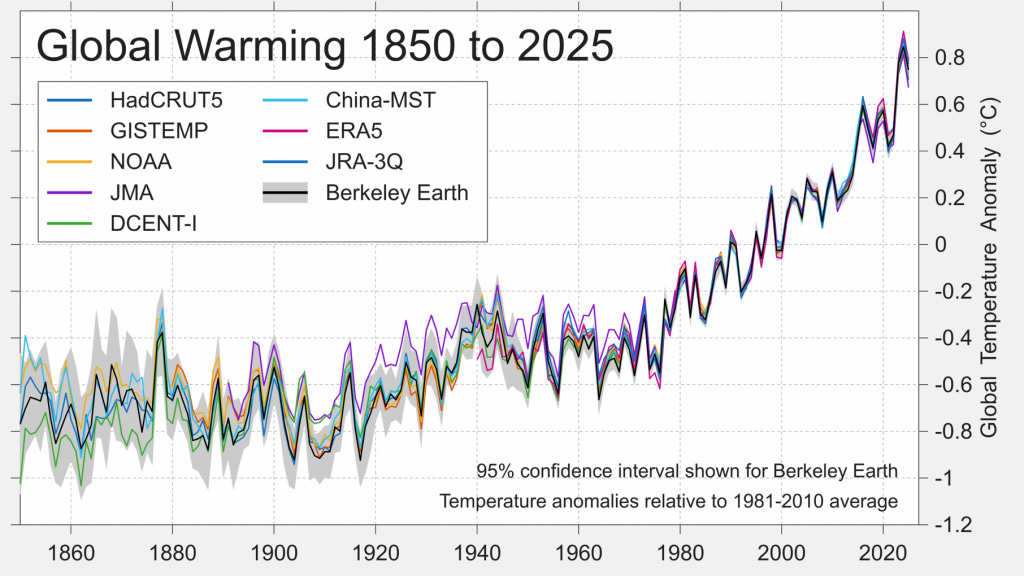

Source: Berkeley Earth

It has been a brutal winter in much of the United States. Weather is a chaotic system in which extreme events are always happening somewhere. But as I am sure you have noticed, extreme weather events — catastrophic storms and flooding, punishing droughts, and yes, extreme cold snaps — are becoming more common as a result of climate change.

For climate change is not just continuing: it’s accelerating. Multiple estimates find that 2025 was one of the warmest years on record for the planet, exceeded only by 2024 and 2023. Indeed, Berkeley Earth reports that “The warming spike observed in 2023 to 2025 has been extreme and suggests an acceleration in the rate of Earth’s warming.”

In other news, the Trump administration has gone to war against any and all efforts to limit climate change. The administration is also imposing a “blockade” against wind and solar projects, delaying or even revoking permits, whether or not these projects have received federal subsidies.

Now, there isn’t a genuine scientific dispute about the reality of global warming and its causes. There isn’t even a serious dispute about the costs of fighting climate change: the economics of green energy are more favorable than they have ever been.

So what’s going on? The Trump administration hates science and science-based policies in general; look at its war on vaccines, which will end up causing an enormous number of deaths. Its assault on universities threatens the best scientific research centers in the world. Its irrational treatment of immigrants means the best and brightest from the around the world no longer want to come here. But in the case of energy, its destructive policy largely reflects the corrupting influence of big money.

I’ll explain in a minute. First, some background.

Almost 40 years have passed since James Hansen’s landmark Senate testimony warning about global warming. He was right. Climate science has been overwhelmingly vindicated by reality.

However, the economics and politics of climate policy have played out very differently from what almost anyone expected.

As late as the 2010s, many observers — myself included — would have said that the big problem in addressing climate change was who would bear the cost. Policies to limit greenhouse gas emissions, everyone believed, would slow the growth of the economy and of real incomes. True, anti-environmentalists were grossly exaggerating these costs. In 2009 I wrote that

[T]he best available economic analyses suggest that even deep cuts in greenhouse gas emissions would impose only modest costs on the average family.

But what we knew at the time nonetheless said that there would be significant costs to slowing global warming. And this was problematic, because the costs of limiting emissions would be incurred right away, while the benefits of reduced warming would accrue decades later — and many of them would go to other countries. So action on climate appeared to require (a) international cooperation (b) persuading voters to accept costs now in exchange for a better world many years in the future.

And it was all too easy to be pessimistic about the prospects both for cooperation and for persuading voters to accept even modest future-oriented sacrifices.

Then came the renewable energy revolution. Solar and wind power have become cost-competitive with fossil fuels — they are, in particular, clearly cheaper than coal. Huge progress in batteries has rapidly reduced the problem of intermittency (the sun doesn’t always shine, the wind doesn’t always blow.) There’s now a clear path for a transition to an “electrotech” economy in which renewable-generated electricity heats our homes, powers our cars, and much more.

This transition would make us richer, not poorer. In fact, nations that for whatever reason fail to take advantage of electrotech will be left behind in global competition.

And at this precise moment — a moment in which acting to accelerate the energy transition would increase, not reduce, economic growth — the U.S. government has been taken over by people who want us to go backward on energy. The Trump administration has even introduced a mascot, “Coalie,” in an attempt to make an extremely dirty fuel cute. But coal isn’t cute. Even if we ignore the role of coal in climate change, coal-burning power plants caused hundreds of thousands of excess U.S. deaths between 1999 and 2020.

What explains this extraordinary rejection of progress and embrace of energy know-nothingism?

Money may not be the whole story, but it’s a lot of the story.

Indeed, much of what is happening to American democracy has its origins in the long-term strategy of the billionaire Koch brothers. The Kochs spent decades promoting right-wing politics in general, with a special role in the takeover of the Supreme Court by the Federalist Society. But an important part of their agenda, and hence that of the right-wing movement as a whole, has always been to keep America burning the fossil fuels on which their wealth rested. If you want to know more, read Lisa Graves’ book on the Roberts Supreme Court, “Without precedent”.

At this point, moreover, it’s not just about normal channels of political influence, nor it just about domestic billionaires. We now live in a time in which U.S. policy is shaped by sheer, naked corruption (enabled in part by the Koch takeover of the courts). Notably, Middle Eastern petrostates, which have a strong interest in blocking the energy transition, have played a huge role in enriching the Trump family.

It’s somewhat surprising that other big-money interests haven’t pushed back. After all, crippling the development of renewable energy is bad for business, and especially bad for the electricity-hungry crypto and AI industries, which ordinarily have a great deal of sway with the Trump administration. But maybe they have decided that special treatment, and especially a green light for their own unethical behavior, matters more than affordable energy.

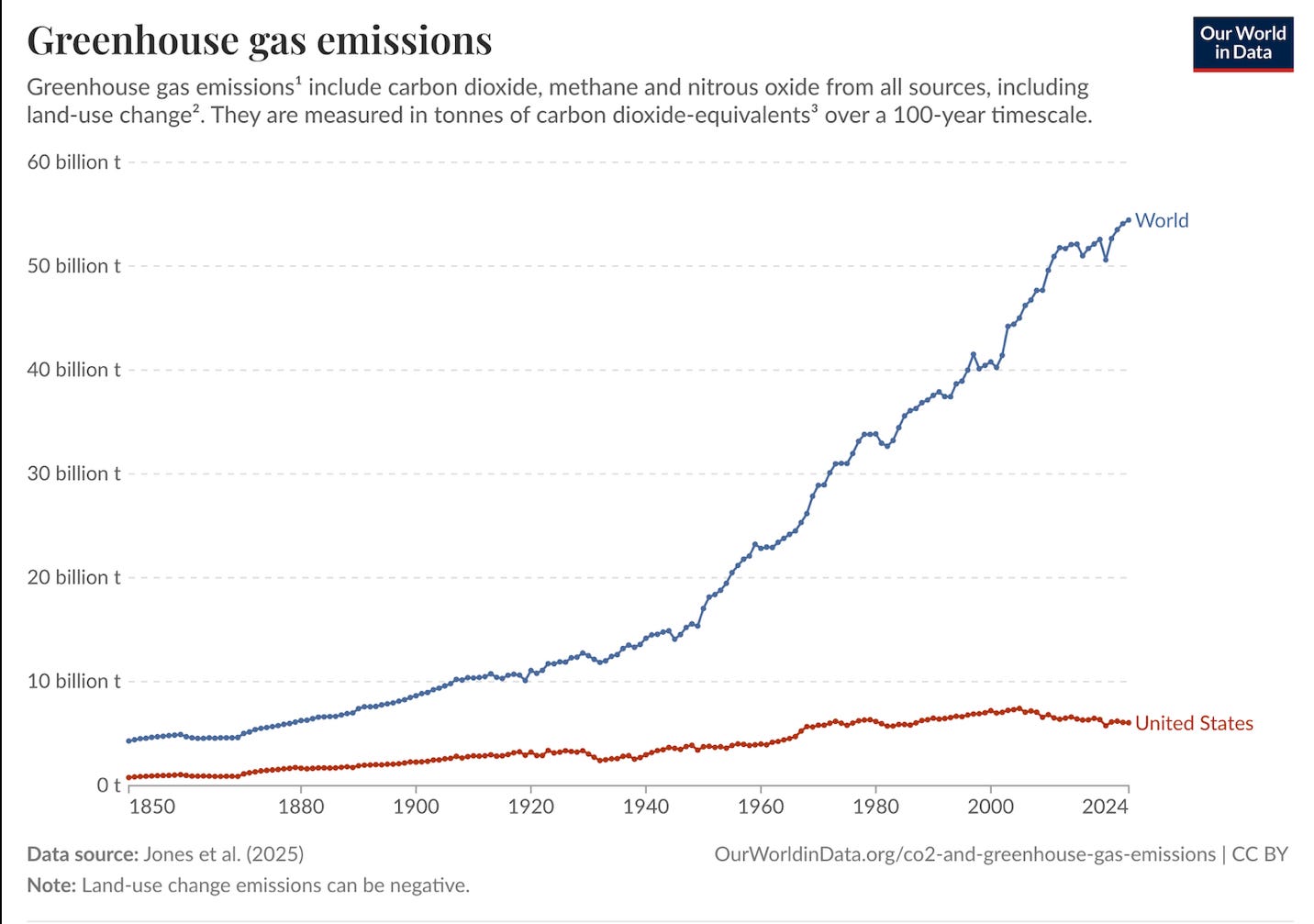

If there’s any good news here, it is that from a global point of view this malignancy may not matter very much. America is not the world. In fact, at this point we’re responsible for only a small fraction of global greenhouse gas emissions:

So America’s hard turn against renewables and climate action won’t be decisive for the climate future as long as other countries continue to move ahead on green energy, which they are. For the most part, all MAGA will do is help make the United States backward, poorer, sicker and irrelevant.

MUSICAL CODA

Over the past decade, India has built the world’s largest real-time payments system. By using public infrastructure to expand financial inclusion, it offers a model for other developing countries that want to modernize payments without being dependent on a few multinational corporations.

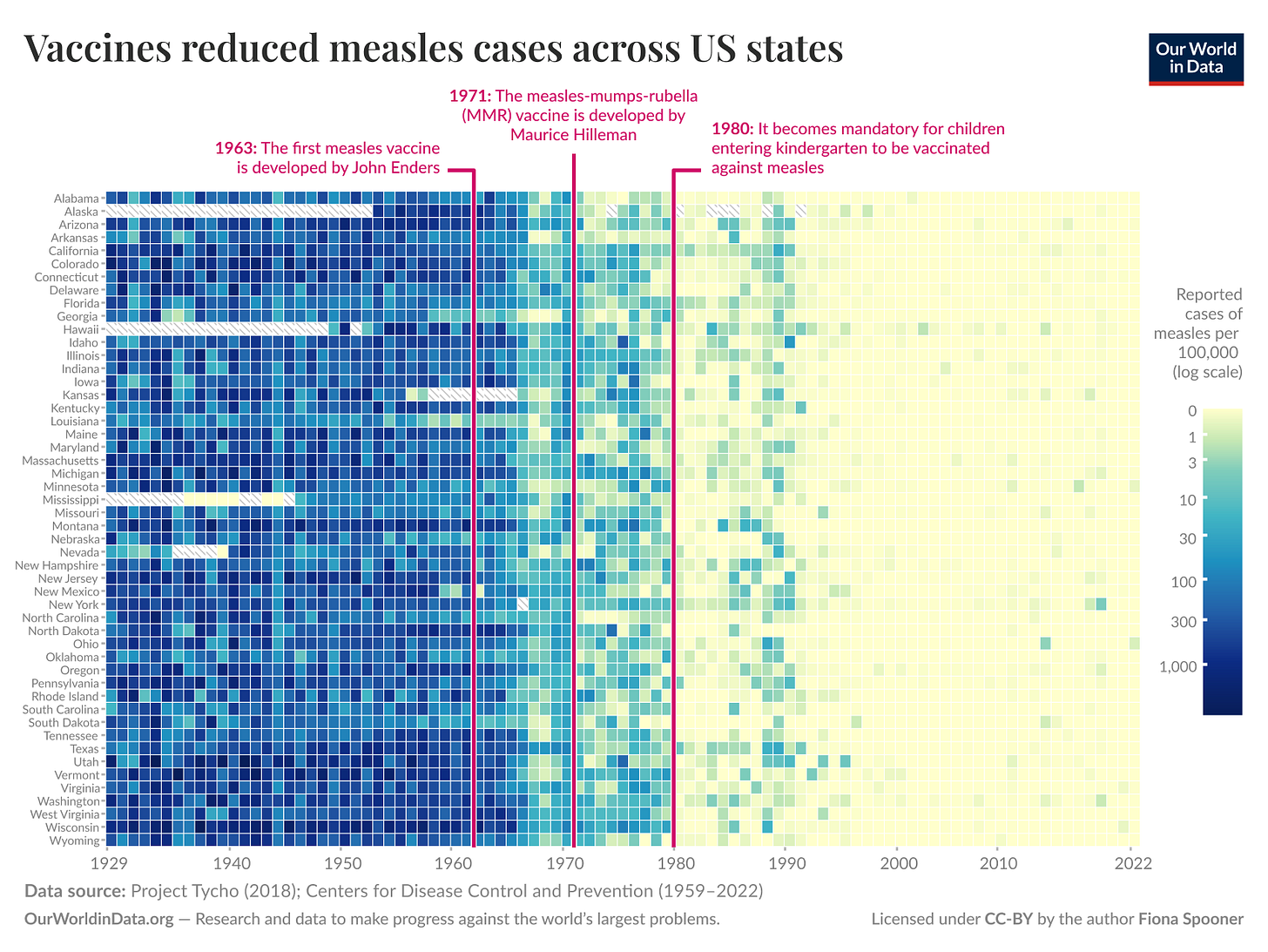

Childhood vaccination is one of public policy’s greatest success stories. People who view the 1950s through rose-colored glasses, seeing them as an era of American greatness, miss many ways in which life was much worse then than now, ranging from gross racism and sexism to high poverty rates among the elderly. One often-overlooked feature of the “good old days” was that many children contracted, and some died from, infectious diseases that have now been almost eliminated — or had been almost eliminated, until today’s right-wing anti-vaccine agitators set the stage for their comeback.

In many ways the Trump administration’s hostility to vaccines is similar to its hostility to clean energy, which I wrote about yesterday. Both policy swerves will kill Americans. If Trumpists succeed in forcing the U.S. to burn more coal, thousands will die from air pollution. Only a year into the Trump 47 administration, there is already a resurgence in almost conquered diseases due to the anti-vax MAGA crusade. Both these sudden policy serves are economically destructive: A 2024 report from the Centers for Disease Control estimated that each dollar spent on childhood vaccination has saved around $11 in societal costs.

Moreover, the Trumpists aren’t content with just cutting off federal funding — they’re determined to stop anyone else from doing the right thing. The Trump administration has imposed a blockade on privately funded wind and solar projects, while RFK Jr.’s allies are pushing to prevent states from implementing childhood vaccine mandates.

And the damage from the assault on vaccines continues to widen. Last week the Food and Drug Administration refused to review Moderna’s new mRNA-based flu vaccine. They didn’t reject it based on evidence; they wouldn’t even look at it, in line with RFK Jr.’s evidence-free, dogmatic assertion that mRNA technology, which gave us Covid vaccines, is useless and harmful. Pharmaceutical companies, understandably, are retreating from vaccine development.

The motivations behind the crusade against clean energy and the crusade against vaccines are also similar. The conspiracy-theorizing hostility to science and expertise in general that underpins both movements also predisposes people to become right-wing extremists, which means that their movements are now in power. The headline on a 2023 article in The Guardian captured this perfectly: “ ‘Everything you’ve been told is a lie’: Inside the wellness-to-fascism pipeline.”

Last but by no means least, in both cases it’s crucial to follow the money.

It may seem strange to think of the wellness industry as a corrupt and corrupting force comparable to the fossil-fuel sector. But wellness is big business. McKinsey estimates that U.S. spending on wellness is running at around $500 billion a year, while spending on nutritional supplements alone was close to $70 billion last year.

And sellers of nutritional supplements, unlike companies selling pharmaceuticals, are effectively allowed to make false, outlandish claims about what their products do. Here’s how the National Institutes of Health summarized the law:

Dietary supplement labels may include certain types of health-related claims. Manufacturers are permitted to say, for example, that a supplement promotes health or supports a body part or function (like heart health or the immune system). These claims must be followed by the words, “This statement has not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. This product is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease.”

In other words, it’s OK to peddle snake oil with false medical claims as long as you mumble some content-freeboilerplate.

And where do the snake-oil salesmen peddle their wares? Largely on right-wing media. After all, that’s where they can find customers who have the right mix of anti-intellectualism and disdain for experts. And the snake-oil purveyors are, in turn, a key part of the extreme right’s financial ecosystem.

I wrote about this almost five years ago. The relationship between quack medicine and right-wing extremism has a long history. As the historian Rick Perlstein has documented, extremists have been marketing medical snake oil, and snake oil purveyors have been financially supporting extremism, since the days when misinformation had to be disseminated through paper newsletters. This mutually beneficial relationship continued through the eras of talk radio, cable TV, and now podcasts.

But now we have entered a new era. As many observers have noted, the Trump administration is a kakistocracy: rule by the worst. A history of personal corruption is no longer a bar to high office — it’s practically a requirement.

Under Trump 47, people who have enriched themselves by peddling medical misinformation are no longer just influencing policymakers. They have become policymakers. Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., who appears to have made millions in salary and book royalties thanks to his anti-vaccine screeds, is now the secretary of health and human services. Dr. Oz is running Medicare and Medicaid.

In short, the kakistocracy is also a quackistocracy.

And the reign of the quacks will condemn thousands, perhaps millions of Americans — many of them children — to gratuitous illness and in some cases death.

MUSICAL CODA

Some Americans have been talking about our shared European culture lately! As CT’s resident American-in-Europe, I feel I must respond. So, here’s a European culture story. (This is Part 2, You can find Part 1 here.)

Okay, so Imperia! Big concrete statue on the shore of Lake Constance. Medieval sex worker. 9 meters tall, weighs 18 tons, rotates once every four minutes. Here she is again:

Let’s look at some details.

Imperia is Ready for her Closeup

In her right hand, Imperia holds this sad chump:

He’s a medieval Emperor. In his own hand he holds an orb, representing universal secular power. He wears Roman-style sandals. He’s naked, and his genitals dangle limply. His expression is glum, dejected, resigned.

In her left hand, this guy:

He’s a Pope. While the Emperor has the physique of an aging athlete, the Pope is a flabby nerd. He’s naked too, but his legs are crossed. He wears delicate little socks with pointy toes. His plump face is pulled into a moue of annoyance. While the Emperor’s body language is limp and drooping, the Pope is tense with irritation. The Emperor is impotent; the Pope is frustrated.

And then there’s Imperia herself:

There’s a lot going on with Imperia, but the detail that catches the eye? Her small, cruel smile.

More generally, everything about her radiates strength, confidence, command. Her head is upright — the flowery ornament emphasizes this — but her eyes are directed very slightly downward, de haut en bas, as if contemplating something beneath her. She’s literally looking down her nose at you.

Her posture is erect, shoulders broad. She’s holding up the two shrunken men without the slightest sign of effort. She’s strong: you can see muscle under her sleeves, and more muscle along her extended thigh.

One foot is off the ground, but this doesn’t suggest imbalance. She’s obviously stepping forward, advancing.

(I found one critic who thought she was inspired by the Minoan Snake Goddess. That’s a pretty deep cut, but… maybe?)

So Imperia went up in 1993. The sculptor was a guy named Peter Lenk, who is still around. I’m not a fan. Most of Lenk’s sculptures are 3-D political cartoons, and they’re usually some combination of ugly and vulgar. He’s got a following, but most of his stuff leaves me flat.

Imperia, though… Imperia, in my opinion, goes pretty hard. I view Lenk as a one-hit wonder, and Imperia is his Macarena.

Scandal at the Council

In the previous post, I went on at some length about the Council of Constance. One detail I omitted: during the years of the Council, 1415-18, Constance was famously full of sex workers.

Makes sense, right? The Council was all men — priests, bishops, noblemen, professors, lawyers. Plus their servants, plus all the workers who came into town to support them. Thousands of men, away from home for years at a time. Obviously there were going to be sex workers. And because Constance was a small city that was drastically overcrowded, the sex workers were really obvious. They couldn’t be herded into a red light district, because there literally wasn’t room.

And this was very much commented on at the time. You had the densest concentration of religious and political elites that Europe had seen in generations. They were here to reform the Church, so that it could provide spiritual and moral guidance to the world. But the moment you set foot in Constance…

The optics were not great. Before long, Europe was abuzz. It was an age of cheap woodcuts, and these told the story better than any thousand words:

[included: hot bath, dinner, musical accompaniment]

And then of course the Council was mostly a failure. Yes, they fixed the problem of the three Popes. But they didn’t solve the Hussite heresy. (In fact, by the brutal judicial murder of Jan Hus, they created a martyr and made it worse.) They didn’t repair the broken system that kept producing bad Popes. And they barely gestured half-heartedly in the direction of reforming the Church.

So Imperia is a sarcastic commentary on the hypocrisy of the Council members, 600 years after the fact? Sure, that works. But I think there’s a lot more going on here. Good art has layers, and while I wouldn’t call Imperia great art, I think she’s a serious work.

Here’s one layer: Sculptor Lenk has acknowledged an inspiration. It’s the short story “La Belle Imperia”, written in 1831 by French author Guy de Balzac.

The Veterinary of Incurable Diseases

I have learned more from Balzac than from all the professional historians, economists, and statisticians of the period altogether — Friedrich Engels

I’m not going to go down a rabbit hole about Balzac, but he was a damn interesting dude. He’s one of those characters who combined a love of life — eating, drinking, chasing women, parties and arguments — with rigorous and terrifying work habits: he wrote over 90 novels plus millions of words of essays and short stories.

Lots of writers have drunk themselves to death. Balzac may be the only one who did it with coffee. He drank forty to fifty tall, strong cups per day, every day, for thirty years. Unsurprisingly he developed heart problems, which claimed his life at the age of 51. (To be fair, the three or four bottles of wine and several cigars per day probably didn’t help.)

Balzac got the odd nickname “vétérinaire des maladies incurables,” possibly because a lot of his stories involved situations that were simply screwed beyond hope of redemption. His short story “La Belle Imperia” fits this pattern. In the story, Imperia is a high-status courtesan at the Council of Constance. A naive young priest falls in love with her, and wackiness ensues.

I don’t think it’s a fantastic story — I’m not a huge Balzac fan to begin with, and I don’t think this is his best — but if you like, you can read it for yourself. And I do think Balzac’s introduction of Imperia is worth noting:

Imperia was the most precious, the most fantastic girl in the world, although she passed for the most dazzling and the beautiful, and the one who best understood the art of bamboozling cardinals and softening the hardiest soldiers and oppressors of the people. She had brave captains, archers, and nobles, ready to serve her at every turn. She had only to breathe a word, and the business of anyone who had offended her was settled. A free fight only brought a smile to her lips, and often the Sire de Baudricourt — one of the King’s Captains — would ask her if there were any one he could kill for her that day… Thus she lived beloved and respected, quite as much as the real ladies and princesses, and was called Madame.

In 1855, Gustave Dore did an illustration of Imperia:

It’s early Dore — he was just getting started — and not that great. Still, we’ll come back to it.

So Imperia is just a story about a very charismatic sex worker who rules men with her wiles? Well… there’s more. Because Balzac got the idea for a courtesan named Imperia from actual history.

Scarlet Woman

There was a real Imperia. Her name was Imperia Cognati, and she lived in Rome around the turn of the 16th century — a contemporary of Machiavelli and Leonardo da Vinci. For about a decade right after 1500, she utterly dominated the Roman social scene. Her lovers included Agostino Chigi. Chigi is now forgotten, but he was the richest man in Italy for decades, and a major patron of the Renaissance.

[as he got richer, his images looked ever more like Jesus]

Rabbit hole avoided: I was going to write a couple of thousand words about Chigi, his monopoly on the alum trade, and how that brought him into head-on conflict with King Henry VII of England, whose grandfather Owen Tudor we glimpsed as a handsome young courtier in the last post. But no. I will note that Chigi was the banker to three Popes in a row. Pope Alexander VI was a murderous gangster, Pope Julius II was harsh and brutal, and Pope Leo X was a cheerful hedonist who drove the Church into bankruptcy. Together, they helped set off the Protestant Reformation!

[that’s Alexander VI. he was pretty evil. good choice for this cover, though.]

Meanwhile: remember in the previous post, where I talked about how the Medici became the Papal bankers by providing money to bribe the College of Cardinals? Well, Chigi filled that position after the Medici left it. And what became of the Medici, you ask? Well, that’s complicated, but part of the answer is that they graduated from helping others become Pope to becoming Pope themselves. Leo X, that fun-loving patron of art and music, was a Medici Pope, and he wouldn’t be the last.

Another of Imperia’s lovers was the painter Raphael.

[“Self-Image Of A University Economics Department“, fresco by Raphael, c. 1510)

There’s a woman who pops up in several of Raphael’s paintings: young, blonde, with high cheekbones and a long nose. We’ll never be completely sure, but it’s widely suspected that she’s Imperia. Here’s an example:

I am not an art guy, but I did take a couple of courses back when. And I remember the professor mentioning that Renaissance Italian artists Had A Thing for blonde models. Olive-skinned beauties do occasionally pop up, but the default female phenotype isn’t very Mediterranean. More like Scandinavia. Or the upper Midwest: give her a parka and a toque and hey it’s Janet Luedtke, sophomore at the University of Wisconsin – Eau Claire.

Anyway! You’ll notice that Raphael gave her a baby unicorn, symbol of innocence and purity. Raphael did like his little jokes.

The descent of Imperia

So now we have a genealogy of sorts.

(1) In 1415 you have the Council of Constance, full of prostitution and hypocrisy.

(2) About 100 years later, you have a real-life courtesan named Imperia. She’s in Rome, not Constance, but she has powerful men as her lovers, is herself a high-status celebrity, and moves in the social circles of the hedonistic Medici Pope.

(3) Around 1830 Balzac writes a short story in which he puts the 16th century Imperia back into the 15th century Council of Constance, because why not.

(4) In 1993, inspired by the Balzac story, Peter Lenk erects Imperia.

That’s good as far as it goes, but now we’re going to complicate it a bit. Because Peter Lenk wasn’t the only creative to be inspired by the Balzac story.

A Little Flesh, A Little History

Back in the early 20th century there was a German painter named Lovis Corinth. Corinth started as a realist, but became much more of an Expressionist after he had a stroke in 1911. Here’s one of his earlier pieces:

[portrait of a woman who’s going to have an interesting life]

That’s Corinth’s student Charlotte Berend, who became a respectable painter in her own right. At the time of the painting, they were lovers. Later they married.

Corinth liked painting women, and he liked painting nudes, and he liked painting nude women. So it’s maybe not surprising that he took inspiration from the Balzac story. He did his own painting of Imperia, in his late Expressionist style:

[Janet Luedtke Gets Drunk And Wins A Bet]

Done in the spring of 1925, it was one of Corinth’s last paintings. A few months later he would die of pneumonia.

Okay, now scroll up to the Gustav Dore engraving about a thousand words back. See the resemblance? Corinth (1925) was obviously riffing on the illustration that Dore (1855) had done 70 years earlier — utterly different style, but same layout.

Now scroll up again and look at the Raphael. Both women are round-faced, pale-skinned blondes with high cheekbones. It’s much less certain, but… maybe Corinth was drawing from Raphael as well as from Dore?

And in the other direction, we know that sculptor Lenk (1993) draw inspiration from the Balzac story (1831). Was he aware of the Corinth painting as well?

Well: on one hand, googling shows no connection. And it doesn’t appear that Lenk ever mentioned the painting.

On the other hand, Lovis Corinth is pretty famous in Germany. And there are some similarities — the upraised arm, the bracelets, the fact that they’re both stepping forward with one (right) foot. And while the painted Imperia isn’t holding up any dwarves, she is utterly dominant over the little dark priest to the right.

Other-other hand, could be coincidence. Or one of those things where an artist just picks up on details from another artist’s work entirely unconsciously. We’ll probably never know.

Also Nazis because really, why not

Corinth’s wife — the former student Charlotte — seems to have been pretty level-headed. Left a widow with two children, she took charge of her husband’s collection and managed it pretty successfully for the next few years, 1925-33. And then the Nazis came to power in Germany.

Did I mention that Charlotte was Jewish? Well, she was. And she seems to have instantly realized what a deadly threat the Nazis were. She left Germany in 1933 with her children, taking some of Corinth’s paintings — she couldn’t get them all out. The family settled in New York City. Charlotte eventually died there, an old lady, in the 1960s.

Meanwhile, back in Germany, Corinth’s remaining paintings were judged by the Nazis and found wanting. A number of them were hung in Goebbel’s “Degenerate Art” exhibition —

[Nazis: fuck those guys.]

— and then several were publicly burned, along with other “degenerate” works of art. So there are various Corinth paintings that we only know from photographs or descriptions.

(But of course, Nazis being Nazis, some of the more interesting paintings quietly slipped into the hands of senior Party members and their particular friends. Every few years another one surfaces somewhere. Yes, eighty years after the end of the Second World War, we’re still recovering paintings that the Nazis looted. Dotted across Europe there are schlosses and chateaus where someone — usually, a very wealthy someone — can appreciate great art in comfort and privacy. Why should they suffer, just because Grandfather had some questionable friends?)

“Imperia” made it to New York, though. She’s in a private collection, but occasionally appears in public for Corinth retrospectives.

I Can Do This, I Swear

All right: this article may have gotten just a tiny bit out of control.

But just one more post, honest. Come back in a day or two and we’ll talk about candy everybody wants, belated respectability, what we see when all that is solid melts into air, and — finally — why I think Imperia is important, serious art, and well worth a look.

Thanks for reading! See you again in a bit.

Yesterday, California Attorney General Rob Bonta filed for an immediate halt to what he says is a widespread price-fixing scheme run by the largest online retailer in America, Amazon. “Amazon tells vendors what prices it wants to see to maintain its own profitability,” Bonta alleged. “Amazon can do this because it is the world’s largest, most powerful online retailer.”

His claim is that Amazon has been forcing vendors who sell on and off the platform to raise prices, and cooperating with other major online retailers to do so.

Vendors, cowed by Amazon’s overwhelming bargaining leverage and fearing punishment, comply—agreeing to raise prices on competitors’ websites (often with the awareness and cooperation of the competing retailer) or to remove products from competing websites altogether. , and it should be immediately enjoined.

Amazon is scheduled for a series of trials in January of 2027, but Bonta’s legal move is a big deal, because he’s asking a court to bring Amazon to heel now, a year early. The only way a judge can do that is if he concludes Amazon is likely to lose, which means that Bonta believes his evidence is so strong it’s basically a foregone conclusion Amazon will be held liable for fostering serious harm to consumers.

The scale of the scheme is almost unfathomable; according to its latest investor reports, Amazon earned $426 billion of revenue in its 2025 North America online shopping business, which is about $3000 for every household in America. As Stacy Mitchell noted, prices for third party goods on the online platform, roughly 60% of its total sales, have been going up at 7% a year, more than twice the rate of inflation. And because this scheme impacts goods sold off of Amazon’s website as well, there’s a reasonable chance that it has had an impact on price levels overall in America. With a similar Pepsi-Walmart alleged conspiracy revealed earlier this year, it’s becoming increasingly clear that consolidation and price-fixing are linked to inflation.

How exactly does the scheme work? Long-standing readers of BIG may remember a piece in 2021 titled “Amazon Prime is an Economy-Distorting Lie” in which I laid out what’s happening. At the time, the D.C. Attorney General, a lawyer named Karl Racine, sued Amazon for prohibiting vendors that sold on its website from offering discounts outside of Amazon. Such anti-discounting provisions raise prices for consumers, and prevent new platforms from emerging to challenge Amazon.

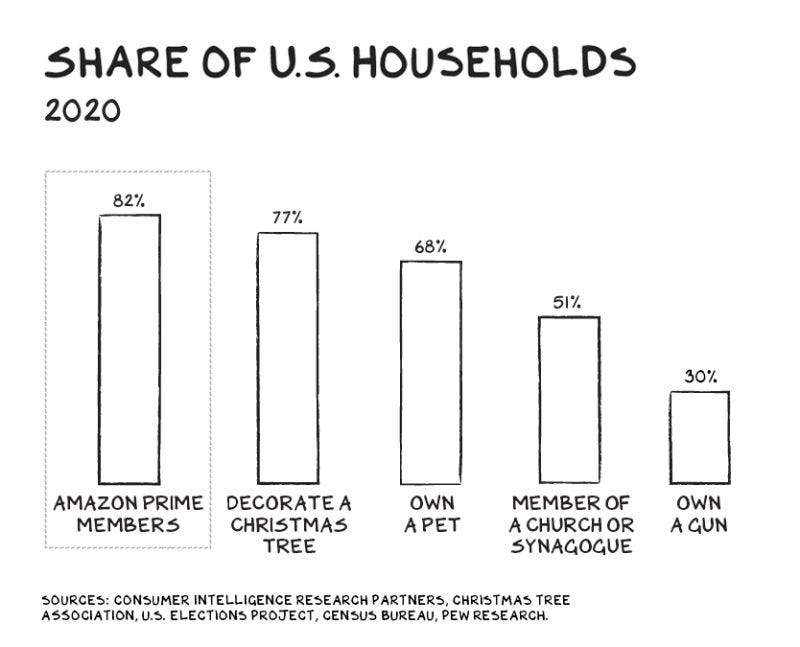

The key leverage point for Amazon is the scale of its Prime program, which has 200 million members nationwide. As Scott Galloway noted a few years ago, more U.S. households belong to Prime than decorate a Christmas tree or go to church.

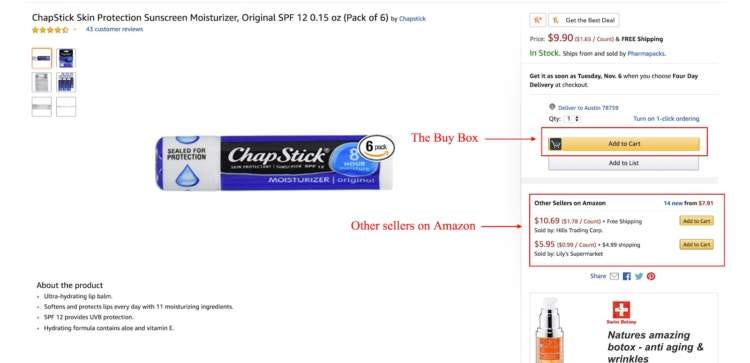

Prime members get ‘free shipping,’ which means they tend not to shop around. They just accept the price and vendor they are given on Amazon through what’s called the “Buy Box.”

So which vendor gets the ‘Buy Box’ and thus the sale to the Prime member? Here’s what I wrote in 2021.

Amazon awards the Buy Box to merchants based on a number of factors. One factor is whether a product is ‘Prime eligible,’ which is to say offered to Prime members with free shipping. In order to become Prime eligible, a seller often must use Amazon’s warehousing and logistics service, Fulfillment by Amazon (FBA). In other words, Amazon ties the ability to access Prime customers to whether a seller pays Amazon for managing its inventory. This strategy has worked - Amazon now fulfills roughly two thirds of the products bought on its platform.

The high prices of overall marketplace access fees, including FBA, is how Amazon generates cash from its Marketplace and retail operations. From 2014 to 2020, the amount it charges third party sellers grew from $11.75 billion to more than $80 billion. “Seller fees now account for 21% of Amazon’s total corporate revenue,” noted Racine, also pointing out that its profit margins for Marketplace sales by third party sellers are four times higher than its own retail sales…

Now, if this were all that was happening, sellers and brands could just sell outside of Amazon, avoid the 35-45% commission, and charge a lower price to entice customers. “Buy Cheaper at Walmart.com!” should be in ads all over the web. But it’s not. And that’s where the main claim from Racine comes in. Amazon uses its Buy Box algorithm to make sure that sellers can’t sell through a different store or even through their own site with a lower price and access Amazon customers, even if they would be able to sell it more cheaply. If they do, they get cut off from the Buy Box, and thus, cut off de facto from being able to sell on Amazon.

The net effect is that prices everywhere, not just on Amazon, are higher than they ordinary would be.

So that’s how the scheme worked, and Racine was the first law enforcer to act. But others followed; Bonta filed his more comprehensive lawsuit in 2022. In 2023, Federal Trade Commission Chair Lina Khan filed against Amazon on similar grounds, though with more details and additional wrinkles. The FTC found that Amazon was running something called “Project Nessie” in which it would use its algorithm to encourage other online retailers, perhaps Walmart.com or Target.com, to raise prices on similar products.

All of these cases, as well as other similar ones, have passed the necessary legal hurdle to go to trial, but an actual remedy is years away. And Amazon keeps growing through this alleged illicit behavior, inflating prices not just on its own site, but across the retail landscape.

According to Bonta, Amazon has three primary methods of inflating prices. In the first one, if Amazon and a competitor are engaged in a price war over a product, Amazon will tell its vendor that sells to its rival to increase the price directly. In the second one, if a competitor is discounting an item, Amazon will ask it to stop through a vendor. And in the third, a vendor will stop selling a product for a lower price outside of Amazon, and Amazon will then raise its price.

This kind of arrangement is known as a “hub-and-spoke” conspiracy, or “vertical price-fixing,” because it’s cooperating on price through common customers or vendors. Such a scheme distinguishes it from direct collaboration among rivals, which is a more standard “horizontal” conspiracy. The relief requested by Bonta is extensive, but amounts to barring the company from making agreements through vendors to set pricing for the online retail economy and prohibiting the company from communicating with vendors about prices and terms for non-Amazon retailers. He is also seeking a monitor to ensure Amazon stops the bad behavior.

What makes it a big deal is that it’s a request for a temporary injunction right now, meant to last until the trial process concludes or it’s otherwise lifted. Judges only grant such injunctions when they think that a party is likely going to lose, the immediate harm of the behavior is significant, and the public interest is served. While we can’t see most of the evidence because it’s redacted, Bonta must really believe he’s got the goods. And if he succeeds in this gambit, it almost certainly means Amazon has violated antitrust law on a major line of business. It also flips the incentives, because Amazon will have less of an incentive to delay a trial. Instead, it will be subject to this injunction until the trial concludes. So it may stop trying dilatory tactics.

There’s one last observation about the complaint. Again, it’s redacted, but Bonta is hinting at Amazon’s internal process to hide what it is doing.

And that wouldn’t be surprising, since the FTC has told the judge in its case that top Amazon officials, including Jeff Bezos, have been destroying evidence.

According to Law.com: “The FTC said in a heavily redacted brief on Friday that it’s missing both the ‘raw notes’ of important meetings and key messages from the Signal apps of Bezos and other senior executives, who, in some instances, set messages to automatically delete in ‘as short as ten seconds or one minute.’”

That kind of behavior is the digital equivalent of shredding documents while under a legal hold, and evidence of lawlessness. And there’s a reason for that. For as long as I’ve been writing BIG, and years before that, laws have not really applied to the rich and powerful. But our work is bearing fruit. And it’s not just Amazon. Today, the Antitrust Division won a big legal motion on its price-fixing case against a meat conspiracy led by Agri-Stats, and the Ninth Circuit had a terrific ruling on a Robinson-Patman Act price discrimination suit. As the people elect new populist politicians, enforcers and plaintiff lawyers are developing the law and the cases to match their frustration.

There’s also a change in public attitudes. In years past, a company like Amazon used to be considered innovative and consumer-friendly. Today, it is understood as bureaucratic and coercive, a result of an environment of lawlessness. Americans are increasingly angry about the situation, seeing the Epstein class and the high inflation environment as a direct threat to their welfare, a conspiracy to extract. Because it is. And at least some elected leaders see that, and are acting to stop it.

Thanks for reading! Your tips make this newsletter what it is, so please send me tips on weird monopolies, stories I’ve missed, or other thoughts. And if you liked this issue of BIG, you can sign up here for more issues, a newsletter on how to restore fair commerce, innovation, and democracy. Consider becoming a paying subscriber to support this work, or if you are a paying subscriber, giving a gift subscription to a friend, colleague, or family member. If you really liked it, read my book, Goliath: The 100-Year War Between Monopoly Power and Democracy.

cheers,

Matt Stoller